- First Name

- Zdeněk

- Surname

- Palcr

- Born

- 1927

- Birth place

- Svitávka u Blanska.

- Place of work

- v Praze

- Died

- 1996

- Keywords

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

Zdeněk Palcr belongs to the influential generation of artists who went to university just after the 2nd World War and managed to study with important figures of inter-war modernism before they were expelled after 1948. From the end of the fifties this generation participated in the massive upsurge in Czech art which lasted throughout the following decade. The important generational focal points included the Josef Wagner studio at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, where Palcr studied alongside Miloslav Chlupáč, Eva and Vladimír Janoušek, Eva Kmentová, Olbram Zoubek, Vladimír Preclík, Zdena Fibichová and the Polish Alina Szapocznikow. Palcr was attracted less by Wagner’s lyricism than by the construction-based work of Gutfreund, and from abroad especially Charles Despiau. Other important influences worth mentioning include the aesthetics lectures given by Václav Nebeský, which subsequently became the starting point of Palcr’s own theoretical approach.

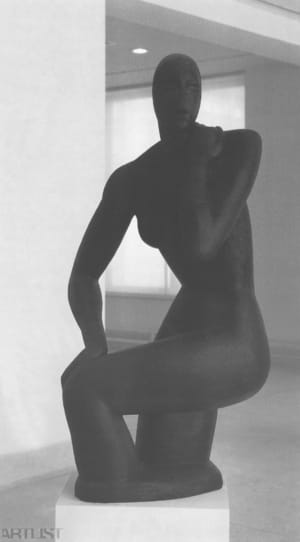

Palcr was always more interested in a pure sculptural form cleansed of literary or decorative accretions. In particular, the first stage of his work in the fifties and first half of the sixties is characterised by the endeavour to achieve an ever more complete reduction of the shape most often depicting the female form. From approximately 1958 more corpulent forms gradually gave way to flattened cubist representations. A fuller female form thus gradually made way for a frontally conceived depiction with implied features of femininity. Later even these disappeared. In the second half of the sixties these flat raised verticals on variously shaped bases have lost their direct link to the organic archetype and Palcr supplements them with protrusions in the form of cylinders, consoles and ledges. Linear elements gradually appear in the form of rods twisted in space, onto which plaster is applied, probably making reference to the outline of the absent figure. The most radical manifestation in this spirit are sculptures conceived of as leaning poles, which the artist later rejected and destroyed. He showed his work from this time at an exhibition in Nová síň in 1970.

The sculptor abandoned the rich morphology of the sixties and devoted himself to perfecting one formal mode – narrow “stelae” with variously conceived base and finish. This involved only a subtle issue of the problematic of overall proportions, processing of the surface, and subtle irregularities in the thickness of the board or the vertical lines, everything taking into account the effect of light. His method of work changed too. Instead of the modelling principle Palcr began using a method in which he applied plaster which he then sanded. In his studio in a former barn in Zdiby, Prague, he would always work on several sculptures simultaneously, returning to them again and again, though never acknowledging the majority of them as finished pieces. An important aspect of his work was long, focussed observation, during which he sought the optimum proportions and made subtle modifications.

Recently certain retrograde elements have appeared in his work, which have seen him combine simple minimalistic shapes with realistic details. However, almost nobody has seen these sculptures since they have not yet been exhibited.

Palcr regarded his sculptures as spiritual works which should not be contaminated by practical considerations. He refused to exhibit them or support himself through sculpture (he characteristically undertook only very few public commissions), but preferred to earn a living through designing film posters (several of which, for instance Forman’s Loves of a Blonde, area amongst the iconic posters of the sixties: Palcr himself was a noted film buff) and restoration (on a contract lasting many years to repair the sgraffito of the chateau in Litomyš, a project he undertook with Stanislav Podhrázský, Václav Boštík and Olbram Zoubek – the project is dealt with in the novel by Libuše Moníková entitled Façade).

From the seventies he was concerned with the written formulation of his creative theory, which was influenced by Václav Nebeský, Petr Rezek and Jan Patočka. It is characteristic that it corresponds to his later creative opinion and yet we do not find any interface with the works of the radical period at the end of the sixties. His texts (three of which – Giacometti’s Perception, The Naive World of a Genius, and the Mysterious Occurrence of a Fact and the Importance of Picture and Sculpture – are particularly important) and interviews were published in the nineties. Despite all the criticism which he attracted (from Jiří Zemánek, Jiří Valoch and Jaromír Zemina) in terms of the negative effect on his work, they are amongst the deepest manifestations of thinking about art which we have in this country from the 20th century from creative artists. He created the texts similarly to the way he created his sculptures at that time: they arose in long time segments, and were gradually supplemented, their ideas and formulations clarified, though this meant they often went beyond the boundary of intelligibility. Palcr follows several basic themes in them, especially the sculpture-object dichotomy. He conceives of a sculpture as a formation with a special character related to the physical existence of man. “The substance of the volume of a sculpture is in a state of harmony with physicality.” The principles of this harmony are above all three-dimensionality, weight and an analogous position in relation to the ground. For Palcr a sculpture carries two basic circles of significance: one is linked to physicality and the second has a relationship with the base. However, both are in contact with the other and are combined in the principle of standing, which in itself carries both an internal physical dynamic and that relationship to the ground which Palcr described as “the connection to the base”. There are two meanings to this: on the one hand the base is that upon which “we physically stand”, that which bonds us to ourselves and from which we cannot escape, i.e. metaphorically speaking physicality as a basic attribute of our existence in this world and as the condition and mission of sculpture. At the same time it is “the world of mothers and fathers, men and women”, a “community of a spiritual whole”, with which we are linked by a similarly fixed bond. Our bondage with the ground is thus metaphorically based on the level of civilised links by which we are determined, physicality is transcended in the direction of the spiritual world. Something similar applies to the sculpture, which is linked by virtue of its weight to the ground, and which also “grows” from the thousands’ of years of development which has gone into it and which determines it to a significant extent. Palcr perceived sculpture as one of the foundation stones of European culture and felt intensely the degradation of its fundamentals and its threatening demise. His resistance to this process determined his conduct as sculptor and man, a man who must find his mission and pursue it with determination if his life is to have any meaning.

Palcr’s work has never been exhibited as a whole and we only know certain works from the studio photos of his friend, Jan Svoboda. The artist himself destroyed a certain part of his oeuvre through his exaggerated self-criticism, while other works are at threat because of their material existence in plaster, the inappropriate handling of his estate and their sheer size. This extraordinary value of Czech art of the 20th century remains to a large extent concealed.

- Author of the annotation

- Marcel Fišer

- Published

- 2010

CV

1945-1950 Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Pragueu. prof. Josef Wagner

1948-49 studied in Sofia (prof. Lazarov)

Since 1957 member of art group Maj

1969-72 member of painters, sculpters and graphic designers section in SČVU

Symposiums:

1967 Vyšné Ružbachy, Slovensko (pracoval zde na soše z minulého roku)

1966 Vyšné Ružbachy, Slovensko

1964 St. Margarethen, Rakousko

- Member of art groups included in ARTLIST.

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

1997

Zdeněk Palcr, Sochy, Miloslav Chlupáč, Kresby, Státní galerie výtvarného umění, Náchod (reprízy 1998 Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích, 1998 Městské muzeum a galerie, Litomyšl)

1996

Setkání, Stanislav Podhrázský – Zdeněk Palcr. Galerie U Bílého jednorožce, Galerie Klatovy – Klenová. Katalog, text Vladimíra Koubová – Eidernová

1986

Václav Boštík – Zdeněk Palcr – Stanislav Palcr – Olbram Zoubek. Samostatné soubory. Galerie Josefa Matičky – dům U rytířů, Městské muzeum v Litomyšli

1984

Malá galerie Stavoprojektu, Brno

1978

Portret rzeźbiarza - Jan Svoboda v pracowni Zdeňka Palcra, Wrocławska Galeria Fotografii, Wroclaw, katalog, text Jaromír Zemina

1970

Zdeněk Palcr, Nová síň, Praha. Katalog, texty Jaromír Zemina, Jiří Šetlík

1960

Zdeněk Palcr, Stanislav Podhrázský, Alšova síň UB, Praha. Katalog, text Miloslav Chlupáč

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2008

Nechci v kleci!, Muzeum umění Olomouc

Pohledy do sbírek Severočeské galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích, Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění, Litoměřice

2007

Od sochy ..., České sochařství 2. poloviny 20. století ze sbírek Galerie Klatovy / Klenová, Galerie U Bílého jednorožce, Klatovy

2005

Opojná plasticita a ztělesnění duchovního světa, Figura v českém sochařství 20. století, Mánes, Praha

Privátní pohled (Sbírka Josefa Chloupka), Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Dům umění, Brno

2004

Flashback, Český a slovenský filmový plakát 1959 - 1989, Trojlodí, Olomouc (repríza

Hotel Thermal, Karlovy Vary., 2004 Dom umenia, Bratislava

Šedesátá, Ze sbírky Galerie Zlatá husa v Praze, Dům umění města Brna, Brno (repríza 2006 Galerie umění, Karlovy Vary)

2002

Svět hvězd a iluzí, Český filmový plakát 20. století, Moravská galerie v Brně, Brno (repríza 2003 Mánes )

2001

Barevná socha, Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění, Litoměřice

Dotyk sochy, Salon, Kabinet, Olomouc

Bilance II, Obrazy a sochy, Galerie umění Karlovy Vary

Jiří Kolář sběratel, Veletržní palác, Národní galerie, Praha

2000

Ozvěny kubismu v českém výtvarném umění, Dům U černé Matky Boží, České muzeum výtvarných umění, Praha

100 + 1 uměleckých děl z dvacátého století Dům U černé Matky Boží, České muzeum výtvarných umění, Praha

1999

Súčasné české umenie (zo súkromej zbierky), Galéria Z, Bratislava

Přírůstky sbírek státních galerií z let 1990 - 1997, Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

Umění zrychleného času, Česká výtvarná scéna 1958 - 1968, České muzeum výtvarných umění, Praha

1998

České umění 1900-1990 ze sbírek Galerie hlavního města Prahy, stálá expozice, Dům U Zlatého prstenu, Galerie hl. m. Prahy, Praha

1996

Umění zastaveného času, Česká výtvarná scéna 1969 – 1985, výstavní síň v Husově ulici, dům U Černé Matky Boží, České muzeum výtvarných umění, Praha (reprízy 1997 Moravská galerie v Brně, 1997 Státní galerie v Chebu)

Zpřítomnění, přírůstky galerie z let 1987 – 1996, zámek Klenová, Galerie Klatovy / Klenová

V prostoru 20. století, České umění ze sbírky Galerie hlavního města Prahy, výstavní sály, Městská knihovna, Galerie hl. m. Prahy, Praha

Eine Promenade der Romantiker, Stadtmuseum Göhre, Jena, SRN

Osudová zalíbení, Sběratelé moderního umění 1900 - 1996, Veletržní palác, Národní galerie, Praha

1994

Z českého výtvarného umění, zámek Litomyšl, Muzeum a galerie Litomyšl

Ohniska znovuzrození, České umění 1956 – 1963, Městská knihovna, Galerie hl. m. Prahy, Praha

1983

Prostor, architektura, výtvarné umění, Výstaviště Černá louka (pavilon H), Ostrava

1972

Sochařské setkání 1972, Vojanovy sady, Galerie hl. m. Prahy

1970

Konfrontace I, Galerie Nova, Praha

1969

V Mostra internazionale di scultura all' aperto, Legnano, Itálie

1968

Deset sochařských vyznání, Síň Fronta, Praha

Socha piešťanských parkov '68, Moderná česká plastika, Kúpeľný ostrov, Piešťany

300 malířů, sochařů, grafiků pěti generací k padesáti letům republiky, Galerie hl., m. Prahy, Mánes, Praha

Začátky generace, Galerie Václava Špály, Praha

1967

Blok tvůrčích skupin – Socha a kresba, Mánes, Praha

I. pražský salon, Bruselský pavilon, Park kultury a oddechu Julia Fučíka, Praha

Sochařská bilance 2, Oblastní galerie Olomouc

Mostra d'arte contemporanea cecoslovacca, Turín, Itálie

1966

Jarní výstava 1966, Mánes, Praha

Aktuální tendence českého umění, Mánes, Nová síň, Československý spisovatel, Galerie Václava Špály, Praha

Avantgarda '66, Mánes, Praha

Sochy, obrazy restaurátorů, Křížová chodba Staroměstské radnice, Galerie hl. m. Prahy, Praha

1965

Małarstwo a rzeźba z Pragi, Krakov, Polsko

Sochařská bilance 1955 - 1965, Oblastní galerie Olomouc

1964

5. výstava Skupiny Máj '57, Nová síň, Praha

Socha 1964, zahrada Oblastní galerie v Liberci a Botanická zahrada v Liberci

1963

Rychnov 1963, Současná výtvarná tvorba, Orlická galerie, zámek, Rychnov na d Kněžnou

1962

Jaro '62, Výstava tvůrčí skupiny Mánes, hostí a Bloku tvůrčích skupin. Mánes, Praha.

Nejmenší kresba, Galerie Československého spisovatele, Praha

1961

Realizace, Galerie Václava Špály, Praha.

4. výstava Skupiny Máj '57, Poděbrady

Plastika v materiálu, Křížová chodba Staroměstské radnice, Praha

Národní galerie ke 40 letům Komunistické strany Československa, Praha a Brno

Sochařská kresba, Galerie mladých, Praha

1960

IV. přehlídka československého výtvarného umění 1959 – 1960. Jízdárna Pražského hradu a Mánes, Praha.

1958

2. výstava Skupiny Máj '57, Palác Dunaj, Praha

3. výstava Skupiny Máj '57 – Grupa Mai 57, Varšava, Polsko

Umění mladých výtvarníků Československa 1958, Dům umění, Brno

1957

1. výstava Skupiny Máj '57, Obecní dům, Praha

1955

Ústřední svaz československých výtvarných umělců, středisko Umělecká beseda, členská výstava. Mánes a Alšova síň, Praha

1946

Výstava volného sdružení veselých umělců (VŠUP). Jídelna staré koželužny,

Praha – Dejvice

- Collections

- Galerie hlavního města Prahy, Galerie Klatovy / Klenová, GMU Roudnice nad Labem, GU v Karlových Varech, GVU v Litoměřicích, Městský úřad v Náchodě, Muzeum narodowe Wroclaw, MU v Olomouci, NG v Praze, OG v Liberci, GVU v Náchodě, VGU v Pardubicích

- Other realisations

Plastika pro Společenský dům, Praha, vápenec, v. 120 cm, 1958 – 60

Plastika pro Čsl. pavilon na světové výstavě EXPO '67, Montreal, Kanada, vápenec, v. 150 cm, 1966

Plastika pro hotel Juventus, Praha, vápenec, v. 100 cm, 1967

Plastika pro budovu Chemapolu, Praha – Vršovice, travertin, 130 x 210 cm, 1968 (ve spolupr. s arch. D. Šestákovou a V. Novákovou)

Reliéfní stěna pro Čsl. pavilon na Světové výstavě EXPO '70 v Osace, Japonsko, litý beton, 4,5 x cca 60 m, 1969 – 70

Reliéfní stěna u budovy TJ Tesla, Brno-Lesná, beton, 2,8 x 25 m, 1982 (ve spolupr. s arch. V. Rudišem)

Plastika (Sedící žena) pro sídliště v Brně-Líšni, pískovec, v. 150 cm, 1988 (ve spolupr. s arch. V. Rudišem)

Monography

- Articles

Zemina, Jaroslav: Zdeněk Palcr. Výtvarné umění, r. 20, 1970, č. 3, s. 122 – 131.

Zdeňkovi Palcrovi, sochaři a příteli, k jubileu 3. září 1977. Vydáno jako samizdat k padesátinám Zdeňka Palcra. Sestavil Jaroslav Anděl. Strojopis. Praha: 1978.

Rezek, Petr: Tělo, věc a skutečnost v současném umění. Jazzová sekce, Jazzpetit, č. 17, Praha 1982.

Rezek, Petr: Haptická ozvěna a haptická ozvěnovitost. Zdeňku Palcrovi k pětašedesátinám. In: Konserva/Na hudbu, 1992, č. 8, s. 31 – 39.

Rezek, Petr: Moře a luk. Text z roku 1992 k pětašedesátinám Zdeňka Palcra. In: Literární noviny, příloha Konserva, r. VII, č. 29, 17. 7. 1996, s. 3.

Koubová – Eidernová, Vladimíra: Obec a půvab. K úsilí zjevit skutečnost duchovního světa budováním figur. Na okraj interview se Zdeňkem Palcrem (Revolver revue, č. 30). In: Architekt, 1997, r. 43, č. 4-5, s. 51-52.

Kapusta ml., Jan: Cesta Zdeňka Palcra k soše. In: Zdeněk Palcr. katalog výstavy. Náchod: Státní galerie výtvarného umění v Náchodě ve spolupráci s nadací Arbor vitae 1997, s. 7 – 45.

Chlupáč, Miloslav: O Zdeňku Palcrovi. In: Zdeněk Palcr. katalog výstavy. Náchod: Státní galerie výtvarného umění v Náchodě ve spolupráci s nadací Arbor vitae 1997, s. 5, 6.

O soše. Rozhovor Karla Srpa se Zdeňkem Palcrem. In: Výtvarné umění 1990, č. 5, s. 23-29. - Palcr, Zdeněk: Giacomettiho postřeh. In: Konserva/Na hudbu 1992, č. 8, s. 3-26. - Měl jsem pocit, že se po mně něco chce... Rozhovor Vladimíry Koubové-Eidernové se Zdeňkem Palcrem. In: Revolver Revue 30, 1995, s. 240-261. - Zemina, Jaromír: Proslov na vernisáži Palcrovy výstavy v Litoměřicích 26. 2. 1998 - Šetlík Jiří: Vzpomínání na Zdeňka Palcra – Chlupáč, Miloslav: Raná léta Zdeňka Palcra - Kolíbal Stanislav: Několik poznámek k povaze Palcrova díla – Petrová, Eva: Sochy zachovávají své jádro v sobě – Zoubek, Olbram: Ahoj Zdeňku - Janoušek, Vladimír: Pro Zdeňka - Janoušková, Věra: Zdeněk Palcr – Svobodová, Anna: Samota Zdeňka Palcra – Janoušek, Ivo: Člověk a umělec Zdeněk Palcr – Valoch, Jiří: Umělec, který se zapletl do vlastního lasa - Zemánek, Jiří: Dvě kacířské poznámky k dílu Zdeňka Palcra. In: Za Zdeňkem Palcrem. Sborník textů z vědeckého sympozia. Editor Jiřina Kumstátová. Litoměřice: Severočeská galerie v Litoměřicích 1999.

Fišer, Marcel: Socha jako význam. K textům Zdeňka Palcra. In: Bydžovská, Lenka – Prahl, Roman (eds.): V mužském mozku. Sborník k 70. narozeninám Petra Wittlicha. Praha: Scriptorium 2002.

Rezek, Petr: Co námi se děje (Pokus o výklad jedné Palcrovy věty) - Proměna plastičnosti - Maskovitá plasticita. In: Rezek, Petr: K teorii plastičnosti. Sborník textů. Sestavila Eva Fialová. Praha: Triáda 2004.

- Personal texts not included in database

Giacomettiho postřeh. In: Konserva / Na hudbu, 1993, č. 10, s. 3 – 26.

Naivní svět génia. In: Konserva / Na hudbu, č. 10, s. 2 – 13.

Podhrázského deset soch a zákon specializace. In: Stanislav Podhrázský. Katalog výstavy v SGVU v Náchodě. Náchod: SGVU Náchod 1995.

Ten, kdo zůstal věrný představě své touhy, neboli Chlupáčovo očekávání. In: Miloslav Chlupáč. Katalog výstavy. Litoměřice: GVU v Litoměřicích 1995.

Záhdaný výskyt skutečnosti a význam obrazu a sochy. In: Konserva / Na hudbu, 1995, č. 12, s. 92 – 132. Přetištěno in: Ateliér, č. 9, 12. 9. 1996, s. 2.

Giacomettiho postřeh. Pracovní verze, leden 1982. Ediční poznámka Michal Blažek. In: Revolver revue, č. 42/2000, s. 267 n.