- First Name

- Benedikt

- Surname

- Tolar

- Born

- 1975

- Birth place

- Plzeň

- Place of work

- Plzeň, Manětín

- Website

- tolarbenedikt.com

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

The work of the sculptor Benedikt Tolar is characterised by a non-violent play making reference to sculpture, and by a cutting humour. This is usually created by the recycling and re-contextualisation of waste or found material. Though the results of his work are close to object, the sculptural background is always clear. Tolar sometimes works in the countryside on land-art installations, e.g. Ark (2011), Blinker (2011).

Tolar has long been working with the comic utilisation of readymades that he combines and transforms into bizarre figures. The beings from the series Menagerie (2000–2011) can be seen as the result of a child’s intuitive game but with a significant admixture of creative intent. Tolar reinvents found materials, finding in them figural motifs and combining them with other waste, leather, bones, etc. These poorly stuffed creatures are made magical using the minimum of material and the artist’s figural conviction. Nevertheless, in their construction we find a certain element of deconstruction and lack, and this gives rise to amusement and embarrassment. A typical example would be Beds (2004), in which Tolar interpreted the screws on a bed frame as eyes and added rubber vampire-like teeth in the centre. This inconspicuous intervention, Kovanda-like in style, significantly changed our perception of an everyday object.

A similar approach to that adopted in Menagerie is to be found in the series Bones (2001–2010) and Figures (1999–2010). All three share a playful and ironic spirit of ingenuity and individual works are linked in a cycle by their formal aspects. Menagerie processes animal motifs, Bones works with a fragment of bone and skull, and Figures with a representation of the human body. These cycles were created over a period of approximately ten years. They were not created in a continuous timeline, but were dependent on the artist discovering suitable materials and defining new functionalities for them.

Bones works on the aspect of modelling. Model I (2001), II (2001), III (2001) are DIY models of aeroplanes and helicopters in which we find a combination of fragments of toys and animal bones. The pseudo-machines then connect technology and the prehistoric hint of skeletal structures. It is for the viewer to decide whether to perceive them as autonomous functioning object-toys or the prototypes of larger works. In Bones there is the prick of a melancholy sarcasm in the form of Last (2010) and Noubady (2008). Noubady is a figure made of an ironing board dressed in a fur coat, and it is remarkable how this synthesis, along with a skull, can create such an emotional impression.

The most astringent feature might be the physical emptiness of Figures, where the human characters admirably accept inanimate items. The form of a person is unquestionable, though has the character of a deflated balloon. Though we may if we like interpret this as connoting the emptiness of contemporary society and the impossibility of enthusiasm and pleasure, the sculptures themselves are full of good cheer and comprehensibility. An almost renaissance elegance of lovers is present in the installation Sencor & Ufesa (2010), in which the names of the lovers are borrowed from the brand names of ventilators. The fact that these formal games are not childish but justified as ideas can be seen, for instance, in Head XXIII (2002), derived from Catch 22 by Joseph Heller.

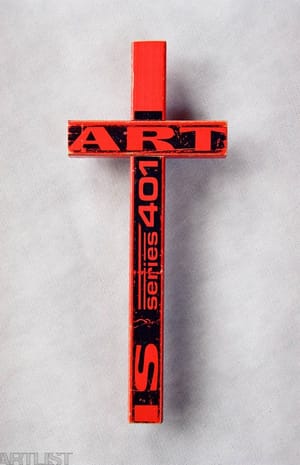

A greater focus on a particular formal element and the variation thereof is present in the cycle of objects Crosses (2004–2012). This is also the moment at which an earlier intentional infantilism is transformed into a more cultivated play. The symbol of the cross is formed by pieces of wooden hockey sticks. Despite the simplicity and clarity of the visual symbols, the work is open to different interpretations. As well as linking fragments of a piece of sports equipment into the shape of a cross, inscriptions appear on the object such as art, brother, professional, team, which are the remnants of the original inscriptions on the hockey stocks. There is a hint of pop-art in this series thanks to the clear symbolism of well known motifs and the expressive colour scheme of the inscriptions. This reference to pop-art continues in the series Fridge I, II, III.

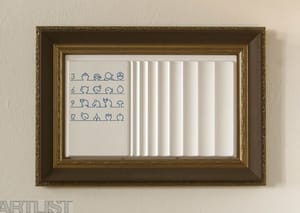

Fridge III (2008–2009) comprises an assemblage of found components of refrigerators placed within mostly ornamental frames. Unlike Tolar’s earlier work, this series is formally more cultivated without losing the earlier ironic distance. If we overlook the frames, the relief of the images is geometrically structured and reminiscent of a minimalist abstract work. However, the stylistic purity is sometimes violated by the descriptive illustrations of types of food, which serve as instructions to storage in the fridge. The transcendental level is thus disrupted by purposefulness, which transfers the abstract objects back into the sphere of the everyday. Again, this is carried out by means of humour.

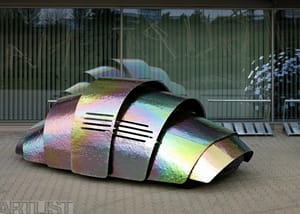

The flatness and abstraction of form in Fridge continues in the sculptures of the series Auto-moto (2009-2011). Tolar continues to use found material, in this case car bonnets. However, formally these sculptures are completely abstracted, extracted from their original function and transformed into artistic objects that create new content. It is far subtler work with readymade and sees the development of a painterly sensitivity to work with surface. The cycle of sculptures Roofs (2007–2013) is directly linked to Auto-moto and takes the roofs of car bodies and installs them on a wall. Tolar leaves the trucks and cars to the fate of cabriolets and their roofs collected as trophies. Painting again makes an appearance. Several roofs are painted in different layers of colour and the surface is then sanded in such a way that a kind of graphic depiction of the contours emerges. Baths (2013-2015) and SAT-ANT (2013-2015) continue this theme, simply using different materials, namely parts of a van, satellites and television antennae.

- Author of the annotation

- František Fekete

- Published

- 2015

CV

Studies:

since 2010

Faculty of Design and Arts Ladislav Sutnar Pilsen, studio and Sculpture Space, an assistant professor

2006–2007

VOŠUP Sand, educator

2005–2010

Institute of Art and Design in Pilsen, studio and Sculpture Space, an assistant professor

2001–2002

Campanus elementary school, teacher

1996–2002

Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, studio of Charles Nepraš Vladimir Skrepl

Internships, creative residencies:

2012

Tour Seegmuller, project - LA ZONE, Presqu'ile Malraux, Strasbourg, France

Awards:

2008

Price 333 Ng and CEZ Group, finalist

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2014

Na plech, Galerie města Plzně, Plzeň

2013

Země nepřátel, spolu s B. Motlovou, Galerie bratří Špilarů, Domažlice

2012

Zdroje a vazby, spolu s Renatou Kocmanovou, Blue Cat Gallery, Cherson, Ukrajina

2011

Odpouštění, Galerie Pecka, Praha

2011

Kráva zajíce nedohoní, spolu s Denisou Krausovou, Galerie Chodovská tvrz, Praha

2010

Zvenku i zevnitř, spolu s Luďkem Míškem, Univerzitní galerie, Plzeň

2010

Trofeje, Galerie U Dobrého pastýře, BKC, Brno

2008

Příbytek, nábytek, dobytek.., Galerie Petrohrad, Plzeň

2005

Divočina, Galerie ad-astra, Kuřim

2003

Bez názvu, Prostor pro jedno dílo, Pražákův palác Moravské galerie v Brně

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2015

Budelip, v rámci projektu Zen Plzeň, náměstí Emila Škody, Plzeň

2015

Od podlahy, Galerie Emila Filly, Armaturka, Ústí nad Labem

2015

Ze středu ven, K 13 Kunsthalle, Košice, Slovensko

2014

Who is the director?, festival 4+4 dny v pohybu, Palác u Stýblů, Praha

2014

Ze středu ven, Západočeská galerie, Masné krámy, Plzeň

2012

Šumavská reflexe, Galerie města Plzně, Plzeň

2012

La zone, Tour Seegmuller, Presqu'ile Malraux, Štrasburg, Francie

2012

Skulpturen - sommer, Botanischen Garten, Ulm, Německo

2012

Odnikud nikam, pro nic za nic, blízko hranic, Klášterní kostel sv. Antonína Paduánského, koncertní a výstavní síň, Sokolov

2012

Věznice - místo pro umění, Moravská galerie - UMP muzeum, Brno

2012

Hraniční polohy tradice, Kvalitář, Praha

2012

Nezvaný host, galerie Chodovská tvrz, Praha

2012

Pilsner schaum, Cordonhaus, Cham, Německo

2011

Věznice - místo pro umění, Centrum současného umění DOX, Praha

2011

Pozdní sběr, Botanická zahrada, Praha

2011

Plzeňská pěna, KGVU - Dům umění ve Zlíně, Zlín

2011

Plzeňská pěna, Galerie města Plzně, Plzeň

2011

Ladový hokej, Múzeum V.Löfflera, Košice, Slovensko

2011

Pilsner schaum, Kunstverein Weiden,Weiden, Německo

2011

Ohrožený duch, galerie Tic, R2, Brno

2010

02:15, Topičův salon, Praha

2010

Fair play, Starý pivovar, Brno

2009

Böhmen liegt am meer (II), Tschechisches Zentrum, Berlín, Německo

2009

X + X 09, Oberpfälzer Künstlerhaus Schwandorf-Fronberg, Německo

2009

Böhmen liegt am meer,Städtischen Galerie Bremen, Německo

2008

Cena NG 333 a skupiny ČEZ, Finalisté, Veletržní palác, Národní galerie v

Praze

2008

Nic na odiv...?, Kateřinská zahrada, Praha

2008

Jiná skutečnost, Galerie města Plzně

2008

Sochy v ulicích/Brno open art 08, Brno

2006

X+X 06, Galerie u Bílého jednorožce, Klatovy

2006

Kvalitní řešení, Galerie moderního umění v Hradci králové

2005

Lesbická škola Karla Nepraše, Dům umění v Opavě

2005

Les, Galerie města Plzně, Plzeň

2005

Socha dnes - Výběr z českého sochařství 1995 - 2005, Veletržní palác, Národní galerie, Praha

2004

Socha v zahradě, Botanická zahrada, Praha

2004

Dole bez, Výstavní síň Karla Pipicha, Chrudim

2003

Po roce, Hořické muzeum, Hořice

2002

Diplomanti AVU, Veletržní palác, Národní galerie v Praze

2002

Jojo efekt, Wortnerův dům AJG, České Budějovice

2001

Hermeneutika aneb šuliny si šeptají, galerie Roxy, Praha

2000

Výstava AVU, Mánes, Praha

1999

Bez názvu, Věž, Liberec

- Collections

-

Národní galerie v Praze

Galerie Klatovy/Klenová

Artotéka města Plzně

Sbírka bratří Markových

soukromé sbírky ČR, USA, Německo, Francie, Turecko

- Other realisations

2015

Beetle, (mobilní plastika), EHMK Plzeň 201

Disco, (mobilní plastika), EHMK Plzeň 20152014

Maminka, Srbice, okr. Domažlice, ČR

V kleci, Čermná, okr. Domažlice, ČR2013

In memorian, Strýčkovice, okr. Domažlice, ČR2012

Flatlet II, Botanischen garten, Ulm, Německo

Monography

- Articles

2014

BROZMAN, Dušan. Na plech: Plzeň, Galerie města Plzně, 21. 8.- 1. 10.; kurátor Jindřich Lukavský. Ateliér. 25.09. 2014, roč. 27, č. 19, s. 3.2011

VAŇOUS, Petr. Tolarova parafráze kódu. Ateliér, 2011, roč. 24, č. 20, s. 4. ISSN 1210-5236.Vaňous, Petr. Dvě hodiny patnáct. Ateliér, 2011, roč. 24, č.1, s. 4. ISSN 1210-5236

2008

JANÁS, Robert. Socha nebo objekt: dva principy současného sochařství. Art & Antiques: váš průvodce světem umění. 2008, léto, s. 36-42.NETOPIL, Pavel. Sochy v ulicích-Brno Art open 2008. A2 kulturní týdeník, roč. 4,č. 26, 25.6.2008, s. 9, ISSN 1801 - 4542

2005

NETOPIL, Pavel. Divočina. Ateliér, 2005, roč. 18, č. 20, s. 4. ISSN 1210-5236.