- First Name

- Hugo

- Surname

- Demartini

- Born

- 1931

- Birth place

- Prague

- Died

- 2010

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

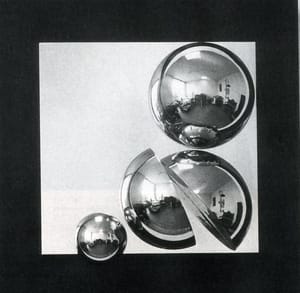

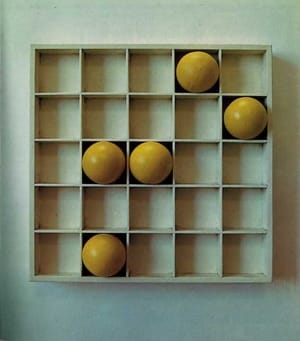

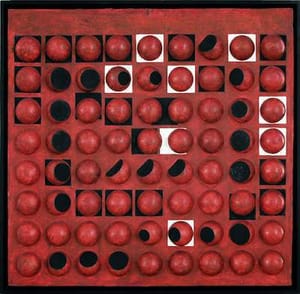

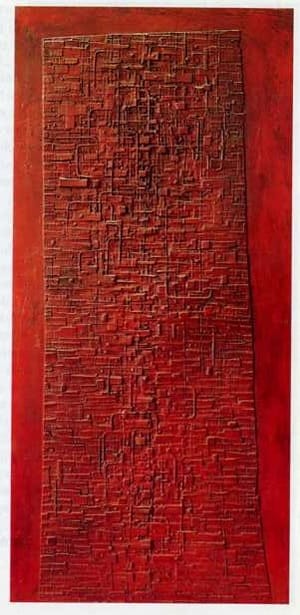

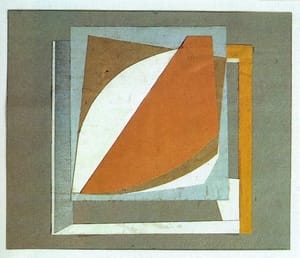

Hugo Demartini was one of the most important representatives of constructivist tendencies in Czech art of the sixties and seventies. However, his work resonates beyond this, beginning with Art Informel and ending with monumental sculptural installations. Demartini received a classical education in sculpture. He began his studies in stonemasonry at the well known Otakar Velínský workshop, after which he studied at the Prague Academy with Professor Lauda. In 1956, after completing his military service (part of which he spent at the Military Art Studio, including two months in Brno with Vincenc Makovský), he completed a cycle of plaster bas-reliefs on a Christian theme, the first of his works displaying a strong, original creative intelligence. Geometric compositions of collages made from coloured paper survive from the end of the fifties. At this time he was also creating traditional busts, though at the turn of the fifties and sixties he moved definitively over to the position of the creative avant-garde of that time and joined the strong current of informal abstraction. His most important contribution is a series of low reliefs created by imprinting small elements in clay and then casting them in plaster, to which he then adds bright red paint. We can interpret these pieces as absurd schemes or as models of the kind of labyrinth we encounter in the work of Sekal. At the same time there is clearly a movement in the direction of a geometric dictionary. This becomes fully apparent in 1964, when the issue of Art Informel was pretty much burned out. A basic surface usually in the shape of a square is divided by a regular grid. Relief elements are inserted in individual cells. At the beginning these are variously cut truncated pyramids, subsequently they are exclusively spheres. The first reliefs are made of coloured plaster, but when chrome plates appear he works only with them. The chrome spheres become the symbol of his creative output. Chrome corresponds more to the impersonal character of the artistic intention which lay behind constructivism, while at the same time expanding possibilities. On the one hand it is a reference to the world of technology, to the “second nature” as it was dubbed at that time, and therefore to contemporary visuality. More important is the element of mirroring, both of the viewer, which establishes a new relationship between viewer and work, as well as of the individual elements themselves, which enter into a mutual optical interaction. Demartini cuts the spheres in various ways, sometimes cutting convex and concave semi-spheres in serial works. At the same time he makes the spheres larger and begins to experiment with various types of boxes in which to insert them. However, the most fundamental experiment involves drawing the spheres out from the purely geometrical background of the underlay and gallery environment and taking them into the landscape. Photography captures the composition of several perfectly burnished chrome spheres on deserted paths or fields.

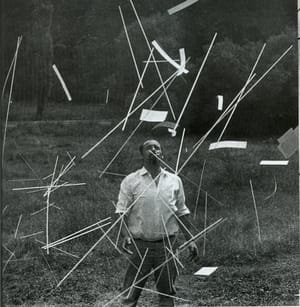

In the same year, 1968, Demartini created a second series of experimental works. These events, entitled Demonstrations in Space, involved throwing items (cylinders, skewers, confetti, etc.) in the air and capturing their random configurations both during freefall and on the ground where they fell. The output of both events is documentation in the medium of photography, though both still relate to the world in question and the space structured by it. Even though they belong to the sphere of conceptual art by virtue of their thematicisation of chance, it is clear that they were created by a sculptor. Demartini did not continue down this path of radical dematerialisation, though it was one of the most up-to-date and interesting strands of Czech art of the time. Over the next few years he developed the previous problematic of minimalist reliefs.

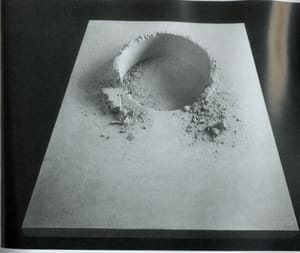

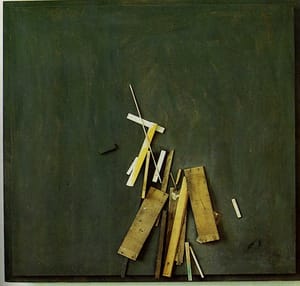

Somewhat later, in 1973, Demartini began a series of objects entitled Out of Bounds, which links directly up to the second of the experiments referred to. These objects involved the careful attachment of items (usually cuttings from models of public events, which at the time represented his means of support) thrown over a hardboard base (most often in the form of a square 110cm x 110cm in size) on this base. The theme of chance links them with the shift taking place at that time in the work of Zdeněk Sýkora, who had at this time moved over to his stochastically generated lines. The works again take the form of a relief, only occasionally intended for horizontal positioning. This corresponds to the process of their creation, a fact which anticipates future works.

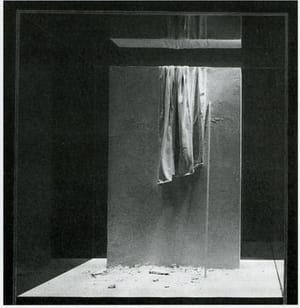

In 1978 one of the reliefs of this cycle – this time under a name that would be often used later, Model – is supplemented with a careful illusion of ruins and decay. This was to become an important element of Demartini’s sculptures, which Josef Hlaváček succinctly described as “geometric formations in various states of disintegration”. The artist first constructs planking, which he covers with plaster. He destroys the resulting shapes with a hammer and immediately fixes the shards – similarly to the way that previously sticks had dropped onto the base – through smearing them with plaster. Certain models, especially those from around the turn of the seventies and eighties with their motifs of hanging drapery, give the impression of stage designs for theatre of the absurd, which incidentally was one of the main inspirational sources of Demartini’s generation. The author then follows these themes of architecturally structured space and disintegration in the final period of his life, which he spent in a rural studio in Sumrakov, not far from Telč.

- Author of the annotation

- Marcel Fišer

- Published

- 2010

CV

Studies

1949-1953 Academy of Fine Arts, atelier of Jan Lauda

1948-1949 Higher School for Sculptors, Prostejov

Employment:

1989-1996 head of the sculpture stdio at the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2008

Akce a proměna geometrické skladby, Topičův salon, Praha

2007

Klub Galerie V kapli, Bruntál

2006

Hugo Demartini a klasická tradice, Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny

Bombírované kresby 1960-62, Minigalerie 6.15, Zlín

2005

Přípravné modely, Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny

Objekty šedesátých let, Galerie Montanelli, Praha

Objekty, Státní hrad a zámek Jindřichův Hradec

2004

Koláže, kresby, objekty, Galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu, Kabinet grafiky a kresby

2003

Galerie Pecka, Praha

2002

Galéria Komart, Bratislava

2000

Retrospektiva, Oblastní galerie v Liberci

Akce a proměna geometrické skladby, Státní galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu

1999

HD 1965 - 1975, Galerie Václava Špály, Praha

Tvorba z let 1965 - 1975, Galerie Aspekt, Brno

1995

Galerie MK, Rožnov pod Radhoštěm

1994

Tvorba z let 1958 - 1978, Dům umění, Ostrava

Dům umění města Brna

1992

Výběr z díla z let 1980 až 1991, Mánes, Praha

1991

Dílo 1964 - 1974, Dům U Kamenného zvonu, GHMP, Praha

1988

Hugo Demartini: Objekty, Jiří Sozanský: Obrazy, Lidový dům, Praha

1986

Hugo Demartini, Pavel Nešleha. Projekty, VS Atrium, Praha

1971

Plastiky 1964 - 1970, Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny

1966-1967 Akce a proměna geometrické skladby, Galerie na Karlově náměstí, Praha

1963

Krajský projektový ústav, Praha

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2010

New Sensitivity, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

2005

Privátní pohled (Sbírka Josefa Chloupka), Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Brno

Prostor a čas, GMU v Roudnici nad Labem

2004

Umění je abstrakce: Česká vizuální kultura 60. let, Staatliches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Mnichov

Ejhle světlo, Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

Šedesátá / The sixties, Ze sbírky Galerie Zlatá husa v Praze, Dům umění města Brna, Brno

Blízká vzdálenost/ Közeli távolság/ Proximate Distance, Szent István Király Múzeum, Székesfehérvár

2003

Ejhle světlo, Moravská galerie v Brně

Umění je abstrakce: Česká vizuální kultura 60. let, Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

Svět jako struktura, Struktura jako obraz, Zámek Klenová, Klenová

2001

Barevná socha, Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích

2000

100 + 1 uměleckých děl z dvacátého století, Dům U černé Matky Boží, ČMVU Praha

Současná minulost: Česká postmoderní moderna 1960-2000, AJG Hluboká nad Vltavou

Jubilejní výstava Akademie výtvarných umění 1800-2000, Valdštejnská jízdárna, Praha

1999

Akce, slovo, pohyb, prostor - experimenty v umění šedesátých let, Městská knihovna, GHMP, Praha

Umění zrychleného času. Česká výtvarná scéna 1958 - 1968, ČMVU Praha

1996

I. nový zlínský salon, Zlín

V prostoru 20. století, České umění ze sbírky Galerie hlavního města Prahy, Městská knihovna

Umění zastaveného času, ČMVU Praha

1994

Nová citlivost, SGVU Litoměřice, OGV Jihlava, Dům umění, Opava, Moravská galerie v Brně

Ohniska znovuzrození, Městská knihovna, GHMP Praha

1993 Záznam nejrozmanitějších faktorů… České malířství 2. poloviny 20. století ze sbírek státních galerií, Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

Příběhy bez konce, Princip série v českém výtvarném umění, MG Brno, NG Praha

Poesie racionality. Konstruktivní tendence v českém výtvarném umění šedesátých let, Valdštejnská jízdárna, Praha

1992

Minisalon, Galerie Nová síň, Praha

Situace 92, Mánes, Praha

1991

Český informel: Průkopníci abstrakce z let 1957 - 1964, Praha

Tradition und Avantgarde in Prag, Kunsthalle Dominikanerkirche, Osnabrück

Šedá cihla 78/1991, Galerie U Bílého jednorožce v Klatovech, Galerie Klatovy / Klenová

1990

Pocta umělců Jindřichovi Chalupeckému, Městská knihovna, Praha

Zaostalí, Galerie Nová síň, Praha

Nová skupina. Městská knihovna, Praha

Zaostalí, Lidový dům, Praha

Konstruktivní tendence šedesátých let, Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích, SG v Praze

1988

Forum 1988, Holešovická tržnice, Praha

1983

Das Prinzip Hoffnung. Aspekte der Utopie in der Kunst und Kultur des 20. Jahrhunderts, Museum Bochum

Prostor, architektura, výtvarné umění, Výstaviště Černá Louka, Ostrava

1981

Netvořice ´81, Dům Bedřicha Dlouhého, Netvořice (Benešov)

1979

Bedřich Dlouhý: Kresby a obrazy, Hugo Demartini: Plastiky, Zdeněk Ziegler: Plakáty,Bechyňská brána, Tábor

1972

50 Jahre Konstruktivismus in Europa, Galerie Gmurzynska, Kolín nad Rýnem

Konstruktive Kunst aus der Tschechoslowakei, Galerie im Erker, Sankt Gallen

1970

Konfrontace I, Galerie Nova, Praha

Klub konkrétistů, Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Brno

Demartini, Kratina, Kubíček, Malich, Sýkora, Alšova síň v Klubu skladatelů, Praha

Tschechische Skulptur des 20. Jahrhunderts, von Myslbek bis zur Gegenwart,Schloß Charlottenburg, Berlín

1969

15 Arte contemporanea in Cecoslovacccia, Galleria Nazionalle d´Arte Moderna, San Marino

Konstruktivismens Ars, Sonja Henies Og Niels Onstads Stiftelser, Oslo

Biennale Nürnberg 1969. Konstruktive Kunst. Elemente und Prinzipien, Kunsthalle Nürnberg

1968

Contemporary Czechoslovakian Art, Jacques Baruch Gallery, Chicago

5 Künstler aus Prag, Galerie Dr. H. Becher, Medebach, Galerie Club Paderborn

Klub konkrétistů a hosté, Oblastní galerie Vysočiny v Jihlavě

Nová citlivost. Křižovatka a hosté. Dům umění města Brna, Dům kultury pracujících Ústí nad Labem, Galerie umění Karlovy Vary, Mánes Praha

Alternative attuali III. Rassegna internazionale d´arte contemporanea. Aspetti della nuova scultura in Europa, Castello Spagnolo, L´Aquila

Sculpture tchècoslovaque de Myslbek à nos jours, Musée Rodin, Paříž

1967

Konstruktive Tendenzen aus der Tschechoslowakei, Studio Galerie der Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität, Frankfurt am Main

Moderne Kunst aus Prag, Caroline-Mathilde-Räume im Celler Schloß, Celle, Wilhelm-Morgner-Haus, Soest, Schleswig-Holsteinischer Kunstverein, Kiel

Konstruktivní tendence, Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny

VI. Biennale d’Arte Repubblica di San Marino. Nuove tecniche d’immagine, Palazzo dei Congressi, San Marino

Jeden okruh volby, Okresní muzeum Písek

1966

Tvůrčí skupina Umělecká beseda, Mánes, Praha

Konstruktivní tendence, GVU Roudnice nad Labem

Nové cesty. Přehlídka současné avantgardy, Dům umění Gottwaldov

Jarní výstava, Mánes, Praha

Konstruktivní tendence, OGV Jihlava

Tschechoslowakische Kunst der Gegenwart, Akademie der Künste, Berlín

Aktuální tendence českého umění. Obrazy, sochy, grafika, Praha

Výstava mladých, Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Brno

1965

Výstava mladých, Výstavní síň ÚLUV , Praha

1964

Umělecká beseda, Mánes, Praha

Socha 1964, Liberec

1958

Umění mladých výtvarníků Československa 1958, Dům umění města Brna

1956

Výstava Grekovova studia Sovětské armády a československých výtvarných umělců, Praha

1955

II. krajské středisko Umělecká beseda, Praha

1953

2. přehlídka československého výtvarného umění 1951 - 1953, Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

1958

Umění mladých výtvarníků Československa 1958. Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

- Collections

-

Alšova jihočeská galerie v Hluboké nad Vltavou

Centre Georges Pompidou, Paříž

Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny

Galerie hlavního města Prahy

Galerie moderního umění v Hradci Králové

Galerie Středočeského kraje, Kutná Hora

Galerie umění Karlovy Vary

Moravská galerie v Brně

Museum Bochum

Museum Folkwang, Essen

Muzeum umění Olomouc

Národní galerie v Praze

Oblastní galerie v Liberci

Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích

Galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu