- First Name

- Jan

- Surname

- Křížek

- Born

- 1919

- Birth place

- Dobroměřice

- Place of work

- Tulle, Francie

- Died

- 1985

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

Jan Křížek’s work is so individual that even within the category of art brut, in which he is usually classified, he is deemed something of an outlier. He received a traditional education in sculpture at the studies of Bohumil Kafka and Karel Pokorný. Perhaps as a result his work, whether it be statuary, drawings, graphic design or collages, is based on figuration. However, he did not take the human figure for the purpose of realist modelling, but as a means of seeking the truth, which was to arise from the depths of the interior and without the participation of reason. Křížek successfully ignored his art education and in doing so attained a means of expression foreshadowing graffiti, while displaying the characteristics of the French artists to whose circle he belonged after his emigration in 1947.

Křížek, along with Václav Boštík and Jiří Mrázek, established the principles of his work, which would remain with him throughout his careers, on the basis of joint considerations as to the path art should follow after World War II. Under the influence of The Spirit of Forms by Élie Faure, Křížek concluded that art cyclically returned to the complete beginning of shapes, and the art of ancient cultures became his starting point. He and his confrères were convinced that a new style would arise on these foundations and that they, with their theoretical considerations and practical application, had a head start on other artists who were at that time working under the influence of expressionism and surrealism. This return to the start meant a revival, the purification of art and the discovery of primordial, archetypal forms. The group was literally obsessed with the Romanesque style and called their own variation upon it Romansh.

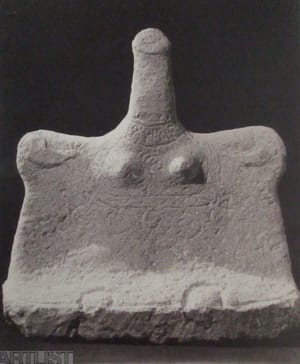

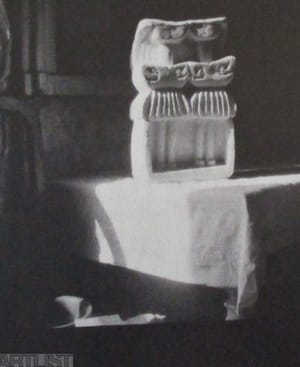

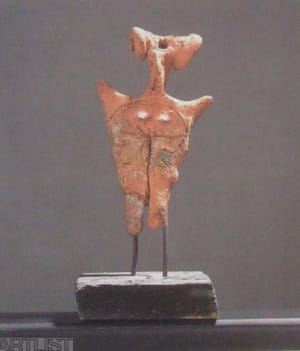

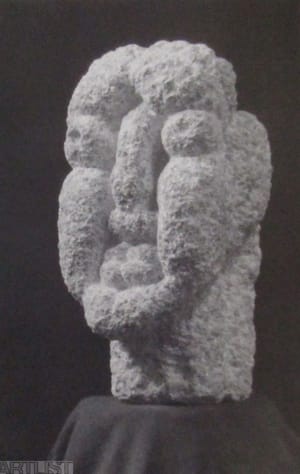

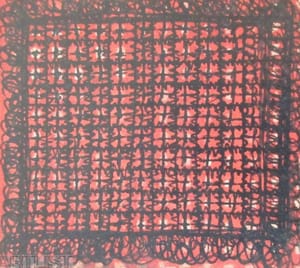

The mutual influence that Křížek and Boštík had upon each other can be seen in their almost identical sculptures (Female Figures, 1940s) or busts. Křížek’s sculptures from this time, namely busts and couples (1940s), sometimes make reference to ancient statues. They return to the original shape using minimal interventions on the stone surface. After cutting the stone into the desired shape, the artist then processed it using only fine engraving. The main material was stone, as in the ancient stages of sculpture (Greek, Cretan, Sumerian, pre-Columbian America) so beloved by Křížek. Through nudes freely inspired by the drawings of August Rodin, Křížek worked his way to simple lines, ornamental grids and colour stains created mainly on a random basis. The resulting drawing is more a record of automatic gesture than a conscious depiction of an idea. The ornament became the main decorative element of even his stone figures.

In 1946 Křížek went on a school trip to France, and a year later returned to the country, having decided to settle there in light of the political turmoil in Czechoslovakia. His timing was perfect, since he arrived in Paris at the height of art brut, tachism, informel and surrealism. Soon after arriving he met the gurus of these styles, Jean Dubuffet, André Breton and Michel Tapié. Upon his arrival, Křížek almost immediately exhibited in 1947 at the Foyer de l’Art Brut, first at a group exhibition (with Adolf Wölflin and Miguel Hernandez) and not long after at the solo exhibition Jan Krizek Sculpteur (1947). This exhibition featured his stone statues, namely busts, couples and embossed figures.

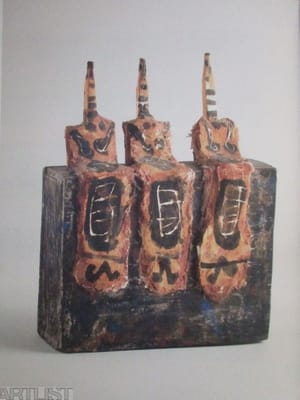

Though highly successful, he decided to quit Paris for material reasons. He moved to the town of Vallauris on the Côte d’Azur, where he began to work with ceramic clay, which he worked by hand without a potter’s wheel. He returned to Paris for the last time at the end of the 1940s. His work was influenced by ongoing material problems that prevented him from creating stone statutes in the absence of a studio and materials. He resorted instead to what he called laboratory work, creating miniature engraved drawings and statuettes from wood or recycled clay.

Křížek thought theoretically about art and its meaning, as we know from his correspondence with André Breton and Václav Boštík. Nevertheless, his work was deeply embedded within the intimate world of its creator, who was reluctant to allow anything of the surrounding world into his sculptures and drawings. It is for this reason that his work appears fresh and spontaneous. The act of creation he believed was a mysterious process involving the search for truth, the origin of everything, and, especially later on, meditation. The concept or idea of the spiritual dimension to creation began to overshadow the art itself. In 1962 he laid down his tools and continued to create only what he called sculpture spéculative. As he wrote in a letter to Boštík: “I have managed to move things to the point that I no longer have to make sculptures, paintings and drawings.” He had reached the point that he and Boštík had pondered from the very start, namely, the very origin of art.

- Author of the annotation

- Zuzana Krišková

- Published

- 2018

CV

Studium: 1937–1938 ČVUT 1938–1939 AVU Praha, ateliér Bohumila Kafky 1945–1946 AVU Praha, ateliér Karla Pokorného 1937–1938 ČVUT Praha

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2013

Jan Křížek (1919–1985) a umělecká Paříž 50. let, Valdštejnská jízdárna, Praha

2012

Síla znaku, Galerie moderního umění v Roudnici nad Labem, Roudnice nad Labem

2004

Jan Křížek, Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny

2000

Jan Křížek, Dům U Rytířů, Litomyšl

1999

Jan Křížek, Galerie Zdeňka Sklenáře, Praha

Jan Křížek, Oblastní galerie v Liberci, Liberec

Obrazy, sochy a keramika, Galerie moderního umění v Roudnici nad Labem, Roudnice nad Labem

1995

Jan Krizek, Musée de la Cohue, Vannes, Francie

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2017

Obraz a slovo v českém výtvarném umění šedesátých let, Výstavní síň Masné krámy, Plzeň

2016

Uhlem, štětcem, skalpelem…, Muzeum umění Olomouc – Muzeum moderního umění, Olomouc

Václav Boštík, Jan Křížek: Tři poklady, Galerie Zdeňka Sklenáře, Praha

2015

Schránka pro ducha, Galerie moderního umění v Roudnici nad Labem, Roudnice nad Labem

2013

Palmy na Vltavě: Primitivismus, mimoevropské kultury a české výtvarné umění 1850–1950, Výstavní síň Masné krámy, Plzeň

2010

Roky ve dnech. České umění 1945–1957, Městská knihovna v Praze, Praha

Moderní český linoryt. On-lino 1910–2010, Galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu, Cheb

2008

Exotismus ve výtvarném umění XX. Století v Čechách a na Moravě, Galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu, Cheb

2004

Tsjechische l’art brut tchèque, Musee därt spontane, Museum voor spontane kunst, Brusel

2003

Václav Boštík, Jan Křížek, Jiří Mrázek, Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny

2002

Černá a bílá, Městské muzeum a galerie, Svitavy

Česká grafika. Půlstoletí proměn moderní grafické tvorby, Mánes, Praha

2000

Tschechischer Surrealismus und Art Brut zum Ende des Jahrtausends, Palais Pálffy, Vídeň

1997

Mezi tradicí a experimentem Práce na papíře a s papírem v českém výtvarném umění 1939–1989, Muzeum umění Olomouc – Muzeum moderního umění, Olomouc

1965

Grafika 65, Galerie Václava Špály, Praha

1952

Členská výstava 1952, Obecní dům, Praha

- Collections

- Národní galerie v Praze Frac Limousin Frac Bretagne Galerie Zdeňka Sklenáře v Praze Galerie hlavního města Prahy Galerie moderního umění v Roudnici nad Labem Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích Galerie Benedikta Rejta v Lounech

Monography

- Monography

PRAVDOVÁ A: Jan Křížek (1919–1985) „Mně z toho nesmí zmizet člověk“, Národní galerie v Praze, Praha 2012 PRAVDOVÁ A: Společný návrat ke kořenům, Jan Křížek a Václav Boštík, in: Konec avantgardy? Od mnichovské dohody ke komunistickému převratu, Arbor vitae, Praha 2011, str. 275-282 NÁDVORNÍKOVÁ A.: Art brut – umění v původním stavu (surovém) stavu, in: Dějiny českého výtvarného umění, VI/1, 1958/2000, Praha 2007, str. 199-205

- Articles

ŠINDELKOVÁ DUFKOVÁ M.: Příběh solitéra (K výstavě a knize mapující dílo Jana Křížka), in: Art+Antiques, 7+8, 2013, str. 10–15 HLAVÁČKOVÁ M.: Návrat k pramenům aneb jak pokračovat od věci označované ke znaku, in: Ateliér, 26, 14–15, 2013, str. 11, 6 PRAVDOVÁ A: Stát se vodivou elektřinou, Korespondence Jana Křížka s André Bretonem, in: Analogon, 64, 2011, 16-21 ŠAFAŘÍK P.: Jan Křížek sochy a včely, DOCUfilm Praha a Česká televize, 2008 SCHMITT B.: Přijetí a odmítnutí automatického poselství, in: Analogon 64, 2011, str. 22-25 LAHODA V.: Archaismus, in: Literární noviny 15, 6, 2004, str. 13 ZEMINA J.: Jan Křížek, in: Revolver Revue, 43, 2000, str. 146-149 PRAVDOVÁ A: „Já jsem otevřel novou cestu, po mně přijdou další, kteří ji rozšíří a povedou dál“, in: Revolver Revue, 43, 2000, str. 135-146 VALOCH J.: Křížkova cesta k syntéze, in: Ateliér, 14, 16-17, 1999, str. 6 ZEMINA J.: Cesta k outsiderům, in: Výtvarné umění, 3-4, 1995, str. 26-32