- First Name

- Jan

- Surname

- Steklík

- Born

- 1938

- Birth place

- Ústí nad Orlicí

- Place of work

- Ústí nad Orlicí a Brno

- Died

- 2017

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

Jan Steklík’s interest in art dates back to his studies at the School of Textiles in his native Ústí nad Orlicí, which he never completed. Instead of an education in the arts, he relied on the university of life, especially the Křižovnická School that he headed along with Karel Nepraš after relocating to Prague. The school’s self-proclaimed ethos, shared by the two men from 1963 onwards, only disappeared with Nepraš’s death in 2002, i.e. only when the poetics of “pure humour without a joke” found itself in competition with the absurdities of the media age, absurdities that would perhaps be beyond the power of even a conceptual artist to invent.

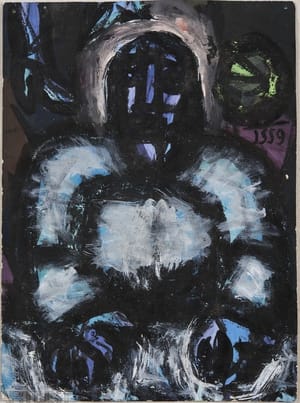

Prior to moving to Prague, Steklík worked for some time as a promotional designer in the Pardubice-based firm Kniha. The minimal demands placed upon him at work left him free to concentrate on his own creative activities. In addition, he came into contact with other artists, thanks to whom he kept abreast of current events on the unofficial art scene and from whom he acquired contacts to the Prague scene. Initially influenced by the structural processes of cubism and the self-referential immediacy of informel, he centred his aesthetic on more rational and expressive means of visual representation, but later gave vent to a fuller feeling for unfettered playfulness suited to more open and active forms of expression. He has retained this sense of fun, which has become the unique distinguishing feature of his aesthetics, permeating all the media and genres he works with. However, this is not to the detriment of an uncompromising expressiveness, which, seemingly paradoxically, Steklík combines with DIY ingenuity, subtle humour, conceptual pranksterism and lyrical hyperbole. These all participate in an all-questioning, Fluxus-style language that can be traced back to the quirky, absurd grotesquery to be found in The Good Soldier Švejk by Jaroslav Hašek.

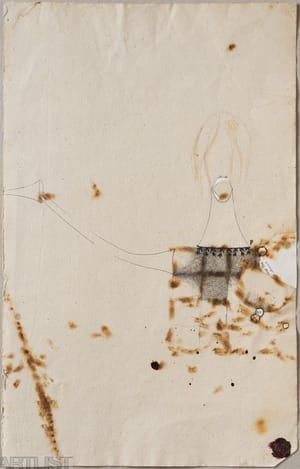

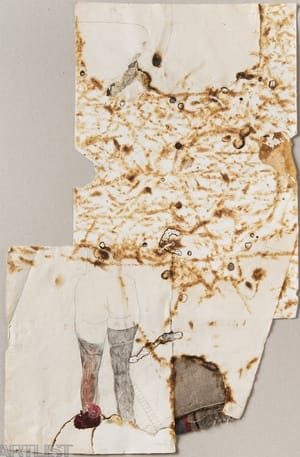

Steklík works mostly with drawing and mixed media. The subtlety and intimacy of the drawn nude suits his inquisitive nature. He plays with the boundaries of drawing as if playing with figures of speech, ignoring the fact that the possibilities of language do not usually correspond to those of visual representation, and that, on the contrary, a short line can often express what takes forever in language. In short, that whereof we cannot speak, Steklík draws! The mundanity of theme corresponds to the subtle means by which it is rendered, which in turn emphasises still further the procedural basis of drawing itself. The artist draws blades of grass, coal, wild mushrooms, etc., and assembles them or simply plucks them from their natural surroundings. He does so without unnecessary pathos but with bravura and nonchalance, the hallmarks of his draftsmanship. Drawing as such is Steklík’s proven conceptual tool and he subordinates other media to it. By means of drawing he designs an airport for clouds, while in fleeting visual structures such as the head on beer, he discovers astral meanings, designs landscapes, or dreams up an encounter between Malevič and Disney. Similar, seemingly banal, sometimes even absurd themes occupy his fantasies and influence his choice of media to work with.

Steklík began deploying semantic ambiguity, the ephemerality of the creative act and media flexibility as far back as the 1960s. He transferred the gestural and structural spontaneity that remained of informel painting to other creative genres, where he combined it with chance, actions, play, humour and unsentimental lyricism. However, as a devotee of a playful aesthetic without interpretative restraints he offers neither impartial indeterminism nor l’art brut. On the contrary, his work is very lyrical and often stylised The burns and perforations to which he subjects his drawings are both passionate and fragile, as if he wanted to express the procedurality, transience and carelessness of all of existence, in Steklík’s case often distanced by means of a subtle irony. He maintains his gentle humour in his conceptual work, installations and actions, especially those on which he cooperated with Karel Nepraš or other members of the Křižovnická School of Pure Humour without a Joke. The group’s eccentric and subversive poetics, pinning its colours to the mast of immediate, often ephemeral creations of resourceful and engaged pub pranksterism instead of the artefacts and commodities of elite art, best corresponds to the aesthetics of play, which Steklík made a tried and trusted method of his art.

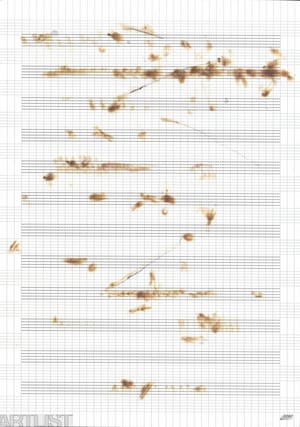

The game permeates all the media that Steklík likes to alternate, intersect or combine. Though he is a minimalist, this is not in the sense of a formal reductionist aesthetic, and he is not interested in material or phenomenological simplification and conversion. He is more interested in revealing the simplest possible solution to fabricated puzzles (which in fact are not really puzzles but are invented for the sheer pleasure of the game), for which he does not need to expose or test media. A clever idea and a healthy common sense amply suffice. This, combined with a ritualistic will to create, the outlook of a prankster and a natural playfulness, bears fruit in the form of charming and brilliantly executed conceptual visual puns – colouring pictures, cutouts, styling, burns, projects, scores, etc. Since the 1960s, Steklík has created these in their thousands, and since he tends not to date his works but keeps returning to tried and tested forms, many can only be assigned an approximate date.

The sheer diversity of Steklík’s interests, positions, themes and forms is extraordinary. He is a master of the accentuation and amplification of seemingly trivial phenomena and events, which he rids of the damaging reputation for banality that either an unthinking social practise or inward looking theory has ascribed to them. Without resorting to pathos or philosophical arguments, he manages to interrogate the very essence and meaning of art (Objednávka na umění / Order for Art), conduct an allusive dialogue with the giants of art (Snídaně v trávě / Breakfast on the Grass, Plešatá zpěvačka / Bald Singer, Noční rybí zpěv / Night-time Fish Singing, Kravaty–houby pro Johna Cage / Ties–Mushrooms for John Cage), draw, cut or burn the ontological intricacies of a drawing (minuscule pen drawings, grass cutouts, burns, landscape cuts) or simply play with media and context. Where others can’t see the forest for the trees, Steklík uncovers in a playful yet sophisticated way inconspicuous yet obvious things, phenomena and processes without which natural and human reality would be impossible and unidentifiable. He is able to elevate the aesthetics of subtlety and unobtrusiveness to a poetic principle. This is also true of his illustrations to dozens of children’s books and magazines. He cooperated mainly with Brno-based publishing companies of the literary journal Host do domu and the ecological journal Veronika, where he found soulmates for his intelligent humour and inventive drawing experiments.

Particular attention should be paid to Steklík’s projects and actions, by which he found his way into the sphere of happenings and land art. He combines conceptual and performative approaches with an ecological environmental awareness that was already partially reflected in his drawings. He moved from the studio and the pub into the open air, not with the intention of representing natural structures and processes, or of staging or installing his own artefacts, but of implementing various collaborative events. On the one hand he remained faithful to the strategy of the Křižovnická School: to alleviate the absurdity of social reality by means of a gentle humorous rephrasing, and on the other to draw attention in a non-violent way to the need for society to revaluate its relationship to nature and its own history.

In Letiště pro mraky / Airport for the Cloud (1970) he burned paper clouds in a field creating by means of smoke signals an iconic and indexical reference to the transience of real clouds. Even more absurd is Inventura Řípu / Inventory of the Říp (1970), a collaborative action with Nepraš, the artist and poet Naděžda Plíšková, and the Canadian writer and translator Paul Wilson, which was carefully documented by the photographer Helena Wilsonová. The protagonists of this work carried out a thorough “inventory” of the immoveable assets of the national symbol, namely Říp Mountain, and documented their findings with all due solemnity. In some of his landscape interventions (Smutek bílého sněhu / The Grief of White Snow; 1969) Steklík tried to attribute human emotions to nature. However, Ošetřování jezera / Treatment of a Lake and Ošetřování stromů / Treatment of a Tree (both 1970) were more about ecological connotations. The artist metaphorically drew an equivalence between care for nature and its ecosystem and care for the human organism, when he treated trees using ordinary medical resources (plaster, bandages, etc.). Steklík’s relationship to nature is neither mimetic nor aesthetic. He does not set out to imitate or stylise the diverse manifestations of natural phenomena, but rather uses them as impulses for a relaxed conceptual appeal for us to realise that the age-old coexistence of human and natural reality is not an eternal state of affairs and that it increasingly depends on our willingness to approach nature with more consideration than we have been capable of up till now. It is still nature that determines the rules for our coexistence with it, not the other way round.

During the 1980s, Steklík moved to Brno. However, he remained faithful to the philosophy of the Křižovnická School even after it had become less active and he himself had been expelled from the Association of Czech Artists in the 1970s. He devoted himself mainly to drawing and illustration, but sporadically also intervened in conceptual and action art, whose creative principles he had adopted over the previous decades. His humour, playfulness and compulsive need to cooperate, both with the audience and other artists, were better suited to open forms. He conceived of most of his works with consideration for the recipient, from whom he expected participation in a game whose rules he often failed to respect himself. Like every game, Steklík’s are liberating. They liberate us from social conventions and free up our asocial urge not to respect them. Steklík uses the game as a tried and tested modus operandi, since it is well suited for its ability to highlight petty phenomena and events. An example of playful cooperation without any limits set on genre would be the actions he realised with Marian Pall: Prádelna / Laundry Room (1996), Maňáskové konceptuální divadlo / Puppet Conceptual Theatre (1997), Místo hudby rum / Rum instead of Music (1998) and Vodovodní umění / Plumbing Water (2005). In 1996 Steklík began an intense collaboration with the German artist Annegret Heinl. Beginning with joint exhibitions, they soon moved onto more interconnected projects and dissolved their individual authorial subjects within joint drawings, objects, installations and performances, in which they applied the playfulness referred to several times, created distance by means of humour, and exhibited a sense for subtle details.

Steklík has a close relationship to many different genres of modern music. Musical influences permeate his work and during the first half of the 1970s he even played the triangle in Nepraš’s bizarre band Sen noci svatojánské band / A Midsummer Night’s Dream Band. He adored progressive jazz and the works of John Cage, in whose honour he created a series of combined drawings. Even in his works inspired by music he applies his hallmark playfulness, exaggeration and wit, and many scores (or interventions in other scores) are more a guide to potential actions than the transcription of possible sounds, and arise more as conceptual visual puns. He created these sporadically from the end of the 1990s onwards, both individual works and cycles, on the basis of external and internal stimuli (listening to music, as tributes to favourite musicians, upon the occasion of their life jubilees, as curatorial commissions, etc.). Although he does not represent the sounds in a conventional musical fashion or create more exact interpretative algorithms, the order and rhythm provoking acoustic realisation in these scores cannot be ignored. It is therefore no surprise that many of them have been performed by experienced musicians.

In addition to music, beer is another of Steklík’s sources of inspiration. As a passionate consumer of the nectar of the gods, he transformed its gastronomic and social effects into poetry. Beer seeps into his work as a spring of metaphor and material substance. The first action was organised jointly with Nepraš at the Křižovnická School (Pivo v umění, Křižovnický kalendář), after which Steklík continued on his own. During the 19970s he took the beer tabs from various pubs and used them as readymade structures in his Pivní kaligrafie / Beer Calligraphy. He published some as samizdat facsimiles and devoted them, as in the case of the later Projekt kosmického pivovaru / Cosmic Brewery Project (1994), to the legendary brewmaster František Ondřej Poupě, who in the 18th and 19th centuries was responsible for huge improvements in brewing in Bohemia and Moravia.

Thanks to his unobtrusive yet uncompromising aesthetic, playful experiences with visual media, hallmark conceptual humour, and a poetics of openness, Jan Steklík has earned a place for himself in the annals of modern Czech art. His feeling for the beauty of nature and simplicity enriched his idiomatic style with an unsentimental lyricism, and he remained loyal to these principles even at an advanced age.

- Author of the annotation

- Jozef Cseres

- Published

- 2017

CV

Studium:

cca 1954–1957 Střední průmyslová škola textilní, Ústí nad Orlicí (studium nedokončeno) Tvůrčí pobyt:

2015 Museum of Avant-Garde, Záhřeb

- Member of art groups included in ARTLIST.

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2017

Steklej humor, Marienbad Film Festival, Mariánské Lázně

2016

Jan Steklík, Kavárna Švanda, Brno;

Jan Steklík a Josef Daněk: Tma a uhlí, Art Space NOV, Pardubice

2015

Partitury, Místogalerie, Brno

2014

Práce na papíře, Galerie Středočeského kraje, Kutná Hora;

Pocta Karlovi Neprašovi, Topičův Salon, Praha;

Partitury pro možnou hudbu neboli každou příležitost (spolu s Annegret Heinl), Památník Leoše Janáčka, Brno

2013

Jan Steklík & Karel Nepraš, Annegret Heinl, Helena Wilsonová, Městské muzeum / Klub Modrý trpaslík, Česká Třebová;

Jan Steklík & Annegret Heinl: Výlet do Broumova, Městská knihovna, Broumov

2010

Jan Steklík – Tomáš Skalík: Double Duel, Komunikační prostor Školská, Praha

2009

Kravaty, houby pro Johna Cage, Galerie Albertovec, Štěpánkovice-Albertovec;

Jan Steklík / Annegret Heinl: Partitury a věže, Městská knihovna, Polička

2008

Jan Steklík / Ladislav Plíva, Galerie pod radnicí, Ústí nad Orlicí;

Jan Steklík: Umění hry, Horácka galerie výtvarného umění, Nové Město na Moravě;

Kravaty-Houby pro Johna Cage & Chlupatý párky, Klub Modrý trpaslík, Česká Třebová;

Jan Steklík: Umění hry, Dům umění, Opava;

Annegret Heinl / Jan Steklík: Winter Garden for 34 Days, Dům umění, Opava

2007

Jan Steklík: Umění hry, Galerie moderního umění, Hradec Králové

2006

Annegret Heinl & Jan Steklík: Obrazy a kresby, Galerie U mistra s palmou, Náchod

2005

Annegret Heinl & Jan Steklík opouštějí Dům umění pomocí Ariadnina provazu, Dům umění, Opava;

Jan Steklík – Marian Palla: Vodovodní umění, Dům umění, Opava

2004

Lamr & Jan Steklík, Galerie města Trutnova, Trutnov

2003

Annegret Heinl / Jan Steklík: Ve staré lékárně, Galerie FONS, Pardubice;

Jan Steklík / Annegret Heinl / Karel Nepraš: Něco z Křížovnické školy, Pouzdřany;

Annegret Heinl / Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík: 1 + 1 + 1 = Feeling + Imagination + Action, Galerie Ungula, Praha

2002

Jan Steklík / Annegret Heinl: Kamenný koberec, Dům umění, Opava;

Jan Steklík / Annegret Heinl, Antikvariát – Galerie Ungula, Praha

2001

Jiří Lacina / Jan Steklík: Sonda do paměti a zpět, Studio Paměť, Praha;

Annegret Heinl a Jan Steklík: Výlet do Opavy, Dům umění, Opava

2000

Annegret Heinl / Jan Steklík: Doubles, Galerie Kunstgewinn, Kolín nad Rýnem

1999

Jan Steklík / Vítězslav Švalbach: Novinová kresba a typografie, Galerie U dobrého pastýře, Brno

1998

Karel Nepraš & Jan Steklík: K. Š., Galerie Ještěr, Česká Třebová;

Annegret Heinl / Jan Steklík, Kolowratský zámek, Rychnov nad Kněžnou;

Karel Nepraš / Jan Steklík, Galerie ve dvoře, Veselí nad Moravou;

Jan Steklík: Kresby, Galerie pod radnicí / Litomyšlská brána, Ústí nad Orlicí / Vysoké Mýto

1997

Sopko – Nepraš – Steklík, Dům umění, Zlín;

Hry Jana Steklíka, Minigalerie Výzkumného ústavu veterinárního lékařství, Brno;

Karel Nepraš a Jan Steklík, Městské muzeum, Broumov;

Karel Nepraš a Jan Steklík, Centrum experimentálního divadla, Brno

1995

Jan Steklík: Ilustrace pro Orlické noviny, Roškotovo divadlo, Ústí nad Orlicí

1994

Koláže, kresby a dokumentace akcí, Státní galerie, Zlín;

Projekt kosmického pivovaru, Galerie U dobrého pastýře, Brno;

Karel Nepraš & Jan Steklík: K. Š., Špálova galerie / Galerie Ve dvoře / Galerie Aspekt / Dům umění, Praha / Veselí nad Moravou / Brno / Opava

1992

Jan Steklík K. Š.: Breastworks, Czechoslovak Centre, Leeds;

Nakladatelství Host, Brno

1991

Informální kresby a koláže Jana Steklíka, Středočeská galerie, Praha

1989

Jan Steklík / Petr Veselý, Okresní kulturní středisko / Studio, Klub mladých, Blansko / Opava;

Jan Steklík: Hry, KSMB, Blansko

1988

Jan Steklík: Prostor 3 – Čára, Galerie H, Kostelec nad Černými lesy

1987

Jan Steklík, Dům umění, Brno;

Galerie Drogerie Zlevněné zboží, Brno;

Kulturní klub, Rakvice

1986

Aleš Lamr / Jan Steklík, Výzkumný ústav ČSAV, Praha 8

1985

Jan Steklík / Dezider Tóth, Městské kulturní středisko SKN, Brno;

Žena v umění (s Karlem Neprašem), Ústav makromolekulární chemie ČSAV, Praha;

Naděžda Plíšková / Jan Steklík: Něha, Vysokoškolský klub, Brno

1983

Karel Nepraš / Jan Steklík, Městské kulturní středisko S. K. Neumanna, Brno

1982

Jan Steklík: Střihy, Městské kulturní středisko, Český Těšín

1981

Jan Steklík, Jednotné kulturní zařízení, Valašské Meziříčí;

Jánské Koupele u Opavy

1979

Klub Kafemlejnek, Jihlava

1978

Jan Steklík: Kresby – Hry, Okresní kulturní středisko, Blansko

1977

Minigalerie VÚVL, Brno

1975

Lamr / Steklík: Obrazy, sochy, kresby, objekty, fotografie, Klub přátel výtvarného umění, Česká Třebová

1973

Aleš Lamr / Jan Steklík, Galerie českého svazu ovocnářů a zahrádkářů, Praha

1972

Karel Nepraš, KŠ / Jan Steklík, KŠ, Dům umění města Brna, Brno

1970

Ňadrovečeře, Oblastní galerie Liberec

1969

Václav Chochola / Jan Steklík, Okresní vlastivědné muzeum, Blansko

1968

Karel Nepraš / Jan Steklík, Dům umělců, Hradec Králové;

Karel Nepraš / Jan Steklík, 10. Haškova Lipnice, Lipnice

1967

Karel Nepraš / Jan Steklík, Klub Moravského muzea, Brno;

Karel Nepraš / Jan Steklík: Kresby a koláže, Minigalerie Čs. spisovatele, Brno

1964

Jirásek / Nepraš / Steklík: Nálezy, OD Pardubice

1961

Karel Nepraš / Pavel Fiala / Jan Steklík: Autostop beze slov, Divadlo Na zábradlí, Praha;

Karel Nepraš / Jan Steklík, Výstavní síň Za pasáží, Pardubice

1960

Jan Steklík / Jiří Toman: Komorní divadlo, Pardubice

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2017

Heinl – Kyncl – Steklík: Three in One. Fons Gallery, Pardubice

2016

Relax, Ben. Dům umění města Brna, Brno;

Partitury ze života, Místogalerie, Brno

2015

Křižovnická škola čistého humoru bez vtipu, Galerie moderního umění, Roudnice nad Labem;

Partitury pro možnou hudbu neboli každou příležitost, Galerie Maldoror, Praha

2014

Druhotvary IV, Památník Leoše Janáčka, Brno;

Jennifer DeFelice, Annegret Heinl, Tomáš Skalík, Jan Steklík, Galerie Cella a Hovorny, Opava;

Vy troubo! pro Jiřího Koláře, Bílý zámek / Galerie Cella a Hovorny, Hradec nad Moravicí / Opava;

Strom – pocta Jiřímu Pruchovi, Galerie Ceasar, Olomouc

2013

Křižovnická škola čistého humoru bez vtipu a její akce na fotografiích Heleny Wilsonové, Galerie FONS, Pardubice

2012

Křižovnická škola čistého humoru bez vtipu, Centrum současného umění DOX;

Membra Disjecta for John Cage, MuseumsQuartier Wien / Centrum současného umění DOX / Galerie výtvarného umění, Vídeň / Praha / Ostrava;

Kották (s Milanem Adamčiakem, Annegret Heinl a Benem Pattersonem), Magyar Műhely Galéria, Budapešť;

Na houby / For John Cage, Gottfrei / Hovorny / Galerie Cella / Divadelní klub, Opava;

Partitury pro každou příležitost (s Milanem Adamčiakem, Annegret Heinl a Benem Pattersonem), Muzeum a galerie Orlických hor, Rychnov nad Kněžnou

2011

Partitury pro každou příležitost (s Annegret Heinl a Benem Pattersonem), Galerie FONS, Pardubice

2010

Hermész füle, Millenáris, Piros-Fekete Galéria, Budapešť;

1 Věž – 4 Věžníci, Novoměstská radnice, Praha

2009

Stopy ohně, Galerie výtvarného umění, Ostrava;

1 Turm – 4 Türmer, Museum Zündorfer Wehrturm, Kolín nad Rýnem;

Igor Kalný / Otis Laubert / Monogramista T. D. / Jan Steklík: Štvorvýstava, Galéria mesta Bratislavy, Bratislava

2008

Jan Zuziak: 64 entomologických krabic, Kavárna Švanda, Brno;

Znova doma s přáteli (Orlický salon 08), Muzeum a galerie Orlických hor, Rychnov nad Kněžnou

2007

Hermész füle, Magyar Műhely Galéria, Budapešť;

Karel Nepraš a přátelé, Krajská galerie výtvarného umění, Zlín

2006

Hermovo ucho, Dům umění / Nitrianska galéria, Opava / Nitra;

His Master’s Freud, Galerie Mona Lisa, Olomouc

2005

IV. Nový zlínský salon 2005, Krajská galerie výtvarného umění, Zlín

2004

Arche Noah vom Rhein, Deutzer Brücke, Kolín nad Rýnem

2003

Typewriting Aloud, Typos Allowed, Baltycka Galeria Sztuki Wspólczesnej, Slupsk;

Annegret Heinl / Karel Nepraš / Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík: Walking from Here to There, Dům umění, Opava;

Prazdroj české kultury: Umění inspirované pivem, Mánes, Praha

2002

Annegret Heinl / Karel Nepraš / Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík: Walking from Here to There, Galerie Behémót, Praha;

300 salonů kresleného humoru, Mánes, Praha;

Sound Off 2002: Typewriting Aloud, Typos Allowed, Galéria umenia, Nové Zámky;

The Rosenberg Museum, Mains D’Oeuvres, Saint-Ouen;

Objekt – Metamorfózy v čase, Moravská galerie, Brno

2001

Mensch!, Anatomischen Institut der Universität Köln, Kolín nad Rýnem;

Annegret Heinl / Karel Nepraš / Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík: Zusammenflüsse und Quellen / Soutoky a prameny, Galerie Gambit / Galerie Kunst Keller Klingelpütz, Praha / Kolín nad Rýnem;

Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík / Annegret Heinl / Karel Nepraš: P.S. : H.N., Galerie Slováckého muzea, Uherské Hradiště

1999

Umění čtyř nápojů, Památník národního písemnictví, Praha;

Annegret Heinl / Karel Nepraš /Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík, Muzeum a galerie Litomyšl, Litomyšl;

Annegret Heinl / Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík, Zámecká galerie / Kolowratský zámek, Opočno / Rychnov nad Kněžnou;

Podoby sdělení, zámek Bystřice pod Hostýnem;

The Rosenberg Museum, V2, Rotterdam;

Zahnräder im Bauch, Alte Feuerwache / MeX / cuba, Kolín nad Rýnem / Dortmund / Münster

1998

The Rosenberg Museum, Galéria K49 / Klub Bar-Oko, Nové Zámky;

Česká koláž, Galleria Communate Del Arte Moderna Contemporanea, Řím

1997

Česká koláž, Národní galerie / Galerie výtvarného umění, Praha / Ostrava

1994

Tovaryšstvo malířské (s Vladimírem Kokoliou, Petrem Kvíčalou a Petrem Veselým), Galerie mladých U dobrého pastýře, Brno

1992

Tvary tónů, Galerie Josefa Matičky, Litomyšl;

Umění akce, Mánes, Praha

1991

Český informel: průkopníci abstrakce z let 1957–1964, Galerie Václava Špály, Praha;

K. Š. – Křižovnická škola čistého humoru bez vtipu, Galerie moderního umění / Středočeská galerie, Hradec Králové / Praha

1990

90 autorů v roce ’90, Palác kultury, Praha;

Offener Dialog: Eine Ausstellung Tsechoslowakischer Künstler aus Mähren, Künstlerforum, Bonn;

Geometrie und Poesie (Chatrný – Rudolf – Sedláková – Steklík), Galerie Comenius, Drážďany

1989

Krejcar / Meister / Nepraš / Steklík, Regionální muzeum, Kolín;

Úsměv, vtip a škleb, Palác kultury, Praha;

Con Amore – Brno, hrad Sovinec

1988

Humor ʼ88, Krajská galerie, Hradec Králové;

Karel Meister – fotografie, Karel Nepraš – plastiky, Jan Steklík – kresby, Galerie Fronta, Praha

1979

10 x 5 kreseb, Jednotné kulturní zařízení, Valašské Meziříčí

1978

Konfrontace 20, Student klub, Brno

1977

Haruyama / Kovanda / Langer / Miler / Mlčoch / Plíva / Richtr / Steklík / Ström / Štembera / Valoch, Vysokoškolský klub, Hradec Králové

1975

Česká vizuální poezie, Institut průmyslového designu, Praha

1971

Keramax, Dům umění města Brna / Okresní kulturní středisko, Brno / Blansko

1969

Křižovnická škola čistého humoru bez vtipu: Crazy Horse Saloon, Paris & Ňadrovky, Závodní klub ROH ČKD, Blansko;

11 giorni di arte collectiva, Pejo;

Partitury, Dům umění, Brno;

Čs. surrealisté, Galerie Grande Jatte / Galerie 7, Brusel / Mons

1968

Humorfestival, Heist-Duinbergen;

Die Logik der dursichtigen Nacht, Čs. surrealisté, Kunstamt, Berlín-Wilmersdorf

1967

Humoristické kresby, Galerie Havlíčkův Brod;

Nová jména, Galerie D, Praha;

9. Haškova Lipnice

1966

Wystawa prac czechoslowackich artystow plastykow, Muzeum Pomorza Środkowego, Koszalin;

Výstava mladých, Moravská galerie, Dům Pánů z Kunštátu, Brno;

Český kreslený humor, Berlín

1965

Kreslený humor, Městské muzeum a galerie, Polička

1964

Přehlídka čs. výtvarného umění „Rychnov 1964“, Zámek Rychnov nad Kněžnou

1962

Kreslená hudba, Divadlo hudby, Praha;

Konfrontace mladých, Klub Mánes, Praha

1961

Výstava obrazů a kreseb (Hajn, Lacina, Novotný, Procházka, Steklík), Výstavní síň mladých, Pardubice

- Collections

- Národní galerie, Praha Moravská galerie, Brno Středočeská galerie, Praha (dnes Galerie Středočeského kraje, Kutná Hora) Muzeum umění, Olomouc Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Drážďany, Německo Muzeum města Brna, Brno Městské muzeum, Ústí nad Orlicí Východočeská galerie, Pardubice Galerie moderního umění, Hradec Králové Státní galerie ve Zlíně, Zlín Horácka galerie výtvarného umění, Nové Město na Moravě Museum Kampa – sbírka Jana a Medy Mládkových, Praha Museo Internazionale della Caricatura, Tolentino, Itálie The Rosenberg Museum, Springwood, Austrálie Kolekcija Marinko Sudac, Záhřeb, Chorvatsko John-Cage-Orgel-Stiftung, Halberstadt, Německo

- Other realisations

Akce (výběr): 2015

Strings Attached (s Annegret Heinl a Hansem W. Kochem), Plato, Ostrava; 2005

Vodovodní umění (s Marianem Pallou); Dům umění, Opava; 1998

Holící diskotéka kolínská voda (s Annegret Heinl, Eugenem Brikciusem a Marianem Pallou), Skleněná louka, Brno;

Čajový obřad (s Annegret Heinl a Marianem Pallou), Galerie U dobrého pastýře, Brno;

Kuličky (pro Chao-Ming Tunga), zámek Kuřim;

Prádelna II (s Marianem Pallou), Divadlo Na zábradlí, Praha;

Houslová čára / Houslová lízátka (s Annegret Heinl), Sound Off / The Rosenberg Museum, Nové Zámky / Violín;

Místo hudby rum (s Marianem Pallou), Skleněná louka, Brno;

Annegret Heinl a Jan Steklík opouštějí Dům umění pomocí Ariadnina provazu, Dům umění, Opava; 1997

Maňáskové konceptuální divadlo (s Marianem Pallou), Skleněná louka, Brno; 1996

Prádelna (s Marianem Pallou), Galerie U dobrého pastýře, Brno; 1994

Projekt kosmického pivovaru, Galerie U dobrého pastýře, Brno; 1987

Šachy, Divadlo na provázku – Divadlo v pohybu III, Brno;

Dublovky, Galerie H, Kostelec nad Černými lesy; 1980

Vycházka do Doudleb, Potštejn; 1979

Dopředstavovánka oběda – plněná paprika s rýží, Potštejn; 1978

Houby, Potštejn; 1976

Geometrická senoseč, Potštejn; 1975

Geometrie na vodě, Potštejn;

Skládání a rozkládání, Potštejn;

Snídaně v trávě, Potštejn;

WC razítkování, Potštejn; 1974

Aleš Lamr / Jan Steklík: Výstava v Anenském údolí, Potštejn;

Fish (s Alešem Lamrem), Potštejn;

Oslava jara, Praha; 1973

Oslava jara, Praha; 1971

Zajíždění bílé čáry, Kunštát na Moravě; 1970

Bílý kruh v trávě, poblíž Ústí nad Orlicí;

Ošetřování stromů (s Rudolfem Němcem), poblíž Ústí nad Orlicí;

Ošetřený stromek (s Rudolfem Němcem), poblíž Ústí nad Orlicí;

Ošetřování jezera, poblíž Poličky;

Bílý pás v lese (s Paulem Wilsonem);

Ňadrovečeře, hrad Lemberk;

Inventura Řípu (s Karlem Neprašem, Naděždou Plíškovou a Paulem Wilsonem), okolí hory Říp;

Letiště pro mraky, hrad Lemberk;

Pivo v umění (kontinuální akce s Karlem Neprašem); 1969

Smutek bílého sněhu (s Josefem Kroutvorem), poblíž Ústí nad Orlicí; Obálky a ilustrace knih: Cílek, Václav – Štěpánek, Václav – Dostál, Ivo: Krajiny srdce. Novela Bohemica, Praha, 2016

Fic, Igor: Vypalování stařiny. Trigon, Praha, 2015

Kratochvil, Jiří: Bleší trh. Druhé město, Brno, 2014

Balabán, Milan: Šepoty a křiky víry. Pulchra, Praha, 2010

Šlosar, Dušan: Otisky. Dokořán, Praha, 2006

Kožmín, Zdeněk: Skácel. Jota, Brno, 1994/2006

Červenková, Jana: Pozdní láska. Atlantis, Brno, 2004

Trefulka, Jan: Skřipce na ptáčky. Atlantis, Brno, 2004

Čechov, Anton Pavlovič: Podvodníci z nouze. Dokořán, Praha, 2003

Romportlová, Ludmila: Černobílé naděje. Atlantis, Brno, 2002

Rychlík, Břetislav: Konec žebřiňáků. Petrov, Brno, 2001

Chvatík, Květoslav: Kniha vzpomínek a příběhů. Atlantis, Brno, 2001

Povolný, Dalibor: Čurající Mikuláš a jiné paranormální historky. Veronica, Brno, 2000

Šrut, Pavel: Konzul v afrikánech. Petrov, Brno, 1998

Švanda, Pavel: Libertas a jiné sny. Atlantis, Brno, 1997

Jeřábek, Čestmír: Cizinec na ostrově. Atlantis, Brno, 1996

Konůpek, Michael: Böhmerland 600cc. Atlantis, Brno, 1996

Švanda, Pavel: Zkušenosti. Atlantis, Brno, 1995

Uhde, Milan: Česká republiko, dobrý den. Atlantis, Brno, 1995

Vian, Boris: Motolice a plankton. Jota, Brno, 1995

Zogata, Jindřich: Psí víno. Sfinga, Ostrava, 1994

Kučera-Kunštátský, Zdeněk: Chytristikon. Jota, Brno, 1994

Skácel, Jan: Třináctý černý kůň. Blok, Brno, 1993

Neubauer, Zdeněk: Do světa na zkušenou čili O cestách tam a zase zpátky. Nakladatelství Michal Jůza & Eva Jůzová, Praha, 1992

Sus, Oleg: Estetické problémy pod napětím: meziválečná avantgarda, surrealismus, levice. Nakladatelství Michal Jůza & Eva Jůzová, Praha, 1992

Šlosar, Dušan: Tisíciletá. Horizont, Praha, 1990

Zogata, Jindřich: Šípkový růženec. MABAN, Brno, 1990

Jůza, Michal: Jednotlivé básně. Pražská imaginace, Praha, 1990

Šlosar, Dušan: Jazyčník. Horizont, Praha, 1985

Rampa, Miroslav – Rampová, Eva: Deset minut po zvonění. Východočeské nakladatelství, Havlíčkův Brod, 1965

Skácel, Jan: Jedenáctý bílý kůň. Krajské nakladatelství, Brno, 1964

Monography

- Monography

Grafické partitury a smyčce. Ad Sensum Bonum, Brno, 2016. (audio CD) Jan Steklík: Grafické partitury. Guerilla Records, Louny, 2015. (audio CD) Nepraš & Steklík: Navzájem, Topičův klub, Praha, 2014. Jan Steklík & Karel Nepraš, Annegret Heinl, Helena Wilsonová. Městské muzeum, Česká Třebová, 2013. 1 Turm – 4 Türmer / 1 Věž – 4 Věžníci. Museum Zündorfer Wehrturm, Kolín nad Rýnem, 2009. Kravaty, houby pro Johna Cage. Budný kámen, Opava, 2009. Kravaty-Houby pro Johna Cage & Chlupatý párky. Triarius, Česká Třebová, 2008. Jan Steklík – Ladislav Plíva. Galerie pod radnicí, Ústí nad Orlicí, 2008. Jan Steklík: Umění hry. Galerie moderního umění, Hradec Králové, 2007. Annegret Heinl & Jan Steklík opouštějí Dům umění pomocí Ariadnina provazu. Dům umění, Opava, 2005. Jan Steklík – Marian Palla: Vodovodní umění, Dům umění, Opava, 2005. Annegret Heinl / Karel Nepraš / Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík: Walking from Here to There. Dům umění, Opava, 2003. Annegret Heinl / Jan Steklík: Kamenný koberec. Dům umění, Opava, 2002. Annegret Heinl / Karel Nepraš / Ben Patterson / Jan Steklík: Zusammenflüsse und Quellen / Soutoky a prameny. Galerie Gambit / Galerie Kunst Keller Klingelpütz, Praha / Kolín nad Rýnem, 2001. Jiří Lacina / Jan Steklík: Sonda do paměti a zpět. Studio Paměť, Praha, 2001. Jan Steklík / Vítězslav Švalbach: Novinová kresba a typografie. Galerie U dobrého pastýře, Brno 1999. Annegret Heinl /Jan Steklík. Okresní muzeum Orlických hor, Rychnov nad Kněžnou, 1998. Jan Steklík: Kresby. Klub přátel výtvarného umění, Ústí nad Orlicí, 1998. Karel Nepraš & Jan Steklík: K. Š. PAF Agency, Česká Třebová, 1998. Marian Palla & Jan Steklík: Prádelna. Galerie U dobrého pastýře, Brno, 1996. Jan Steklík: Projekt kosmického pivovaru, Galerie U dobrého pastýře, Brno, 1994. Jan Steklík – koláže, kresby a dokumentace akcí. Státní galerie, Zlín, 1994. Tovaryšstvo malířské. Galerie mladých U dobrého pastýře, Brno, 1994. Karel Nepraš & Jan Steklík: K. Š. Špálova galerie / Galerie Ve dvoře / Galerie Aspekt / Dům umění, Praha / Veselí nad Moravou / Brno / Opava, 1994. Jan Steklík K. Š.: Ňadrovky / Breastworks. HOST, Brno, 1992. K. Š. – Křižovnická škola čistého humoru bez vtipu. Galerie moderního umění / Středočeská galerie, Hradec Králové / Praha, 1991. Geometrie und Poesie (Chatrný – Rudolf – Sedláková – Steklík). Galerie Comenius, Drážďany, 1990. Jan Steklík / Petr Veselý. Klub MDK PB, Opava, 1989. Jan Steklík / Dezider Tóth. Městské kulturní středisko SKN, Brno, 1985. Jan Steklík. Dům umění, Brno, 1984. Kresby pro Opus musicum. Opus musicum, Brno, 1984. Jan Steklík: Střihy. Městské kulturní středisko, Český Těšín, 1982. Jan Steklík. JZK, Valašské Meziříčí, 1981. Jan Steklík: Kresby – Hry. Okresní kulturní středisko, Blansko, 1978. Lamr / Steklík. Klub přátel výtvarného umění, Česká Třebová, 1975. Karel Nepraš, KŠ / Jan Steklík, KŠ. Dům umění města Brna, Brno, 1972. Výstava obrazů a kreseb. Umělecká sekce mladých, Pardubice, 1961.

- Articles

Drápal, Vladimír: Výtvarník Jan Steklík a křížovnický humor bez hranic. In: Xantypa 7-8/2016. Karlík, Viktor – Cudlín, Karel: Jan Steklík. In: Revolver revue 103/2016. Štěpánek, Václav – Hudec, Karel: Pár střípků o Mistru kreslíři. In: Veronica 2/2013, s. 54. Zhoř, Igor: Cesty za Janem Steklíkem. In: Sborník památce Olega Suse, samizdatové vydání, Praha – Brno, 1988, s. 51-58.

- Other critical texts

Internetová encyklopedie dějin Brna – Osobnosti Slovníkové heslo „Jan Steklík“. In: Nová encyklopedie českého výtvarného umění, Academia, Praha, 1995, s. 784-785. Kdo je kdo v České republice?, Modrý jezdec, Praha, 1994, s. 532.