- First Name

- Jan

- Surname

- Švankmajer

- Born

- 1934

- Birth place

- Prague

- Place of work

- Prague, Horní Staňkov

- Website

- www.athanor.cz

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

In 1977, Vratislav Effenberger signed Charta 77 on behalf of the entire Surrealistic group the members of which at the time included Alena Nádvorníková, Karol Baron, Martin Stejskal, Juraj Mojžíš, Emila Medková, Ludvík Šváb, Albert Marenčin and Eva and Jan Švankmajerovi, among others. Effenberger accompanied the position of the surrealists to the signing with a text in which he openly opposed any power system whether it was the Communist regime or capitalistic style democracy. This standpoint serves as an example of the surrealists’ approach to the political situation at that time. They did not remain indifferent to the current situation, they did not turn to escapism as some of their actions could insinuate, but, on the contrary, they defended a clear and specific critical opinion. They found themselves in double opposition as Effenberg later called it; they retained, however, their own field of thought, free for individual creation of opinions and sufficiently opened to imagination. Such a position can also serve as an instruction how to characterize the free art work of Jan Švankmajer.

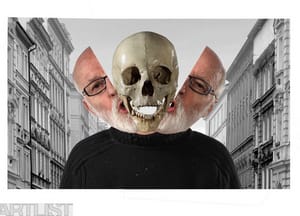

It is precisely imagination that serves surrealists as an instrument for questioning any intellectual or emotional conventions. The power of imagination lies in the fact that it strives to disrupt learned perception and stereotypical ways of learning. In order for a new, metamorphosed world to be created, the original one has to be destroyed. That is why surrealistic actions will always be accepted in a negative way because reason hinders adaption to a new situation. In his work, Jan Švankmajer puts an emphasis precisely on the unaware component of the psyche; the disruption of existing conventions, however, does not remain only in the content aspect. Švankmajer also experiments with actual media, which he uses, whether it is an object, puppet theatre or film.

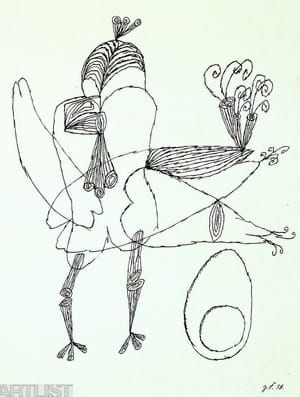

His first independent artworks originated during his studies at the Academy of Performing Arts (1954–1958) where Švankmajer pursued the double-major in fine arts and direction. Initially they are drawings referring to primitivist and overseas art, and later they are objects and bas-reliefs, which are very similar to Czech informel but evade this classification. In his assemblages Švankmajer interconnects diverse materials and objects and allows them to speak for themselves. It is not only a game of association with random things, instead he rather tries to reveal stories through random groupings and memories concealed behind them. According to Švankmajer things have their own memory, which one can haptically relate to. “For me objects have always been more vital than people; more stable, but also more expressive. More exciting with their latent contents and memory far exceeding human memory. Objects conceal stories, which they have witnessed (…) The more an object has been touched, the more its content is charged,” Jan Švankmajer writes in the magazine Film a doba (Film and Time), 1982. The artist’s assemblages can hardly be classified within the tradition of Czech informel, because rather than striving for existential expression or resistance to imagery and formality of modernism, he strove for a specific encounter of shapes, which he further developed at the beginning of the 1960s.

Hi material assemblages in which matter succumbed to varied shaping, kneading and interconnecting, related in their form with the difficult time period in which Jan Švankmajer tried to experiment with puppet theatre. And this was not only in his final exam project from the year 1958, which was the production of the satire by Venetian playwright Carlo Gozzi from 1762 The Stag King, but also later in his own ensemble Theatre of Masks, which functioned for several years under the umbrella of Semafor Theatre. For Švankmajer the medium, whether it was film or theatre play, never played a role of the intermediator of the story. It was rather a field for examination of the boarders between genres and disrupting traditional positions. Relationships between actors and puppets, between the living and nonliving are emphasized in Švankmajer’s early puppet shows. Questions arise here regarding conflicting binary compositions between vital organic nature and illusion of life, between the controlling and the manipulated. Švankmajer’s experimental games inspired, in their form, by Russian and German avant-garde film and theatre, were not very well received by the public at the beginning of the 1960s. Repetitive misunderstanding from the side of the audience and disagreements with the management of the Semafor Theatre led to the moving of the Theatre of Masks ensemble under the umbrella of Laterna Magika in 1962, where Švankmajer was enchanted by the possibilities of a different media – the film.

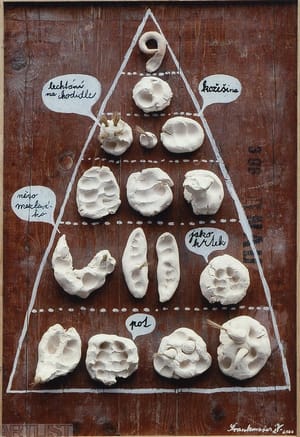

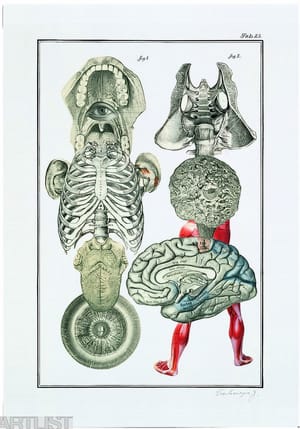

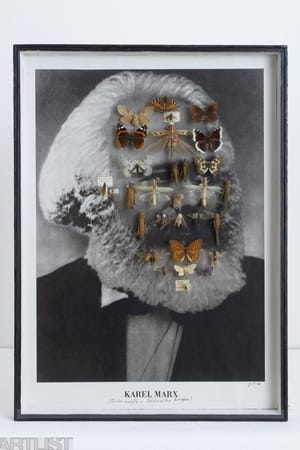

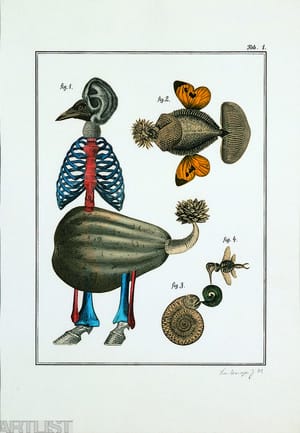

During the same time period Švankmajer’s work is starting to be penetrated by his fascination with Prague Mannerism, the collection of Rudolf II. and the work of Giuseppe Arcimboldo. He creates assemblages where products of nature, created artefacts and drawn and written documents are all encountered in one object. Individual articles are matched together according to loose associative relationships and occasionally they are also labelled and numbered like in classicist natural science collections. Between the years 1971 to 1972 Švankmajer started to create a cycle of collages and graphics, which he called Švank-meyers Bilderlexikon. This title works with the artist’s name and the title of 52-volume encyclopaedia Meyers Lexicon, but it is far from being a stiff scientific catalogue. Švankmajer’s ensemble is some sort of imaginary and utopian encyclopaedia, which tries to include all areas of human knowledge – biology, geography, art, technique, etc. He came back to this project in the 1990s with his collage Systemless Anatomy. Related to encyclopaedia is another collection, however – assemblages from animal skeletons and various objects, which Švankmajer interconnected in diverse fantastic shapes of strange animals and creatures. He later used assemblages in the film Alice (Něco z Alenky) (1987) and they also became the foundation for section Scientika of the Kunstkomora (Kunstchamber) (or as the artist calls it himself: Kunstcamera), which he built in his house in Horní Staňkov. Švankmajer’s Kunstkomora fully reveals the artist’s approach to creative work and the way he sees the world as a “magic universe”, in which the main role is played by imagination as the “queen of human abilities”.

It is not only Švankmajer’s older theatre productions that contain contrasts between traditional approaches and new experiments with images and actors, hybridism of classical methods and combining of genres, these can also be found in his films. Such films continue to be in opposition to the conventional way of filming and also to the perception of the audience. At the same time they are always received with disconcertion, enfolded in provocative undertone, in spite of the fact that Švankmajer’s older films belong among the classics of Czech cinematography. Already when the young Švankmajer was completing his studies at the Academy of Performing Arts in 1958, he received an offer from director and screenwriter Emil Radok to cooperate on short-footage film Johanes Doctor Faust. Six years later Švankmajer produced his own original short film The Last Trick (Poslední trik pana Schwarcewalldea a pana Edgara), which a number of actors from the Theatre of Masks cooperated on. In this film Švankmajer combined some sequences from his theatre plays and from the very beginning he places the viewer in front of a sequence of fast image clips, thanks to which he builds a dynamic and contrasting structure of some sort of anti-narrative. The same principle then recurs in many other Švankmajer’s films, like in the short film Historia naturae (suita) from 1967, where he gradually introduces the viewer to varied natural-scientific species and combines artefacts with products of nature (stuffed as well as living) and drawings. The film originated parallelly to his interest in Rudof II. Mannerism and fantastic creatures, which Švankmajer visualized in his collages and objects.

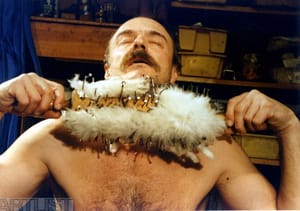

During the 1970s Švankmajer was not allowed to work on films and he alone did not have sufficient technical equipment to be able to make films on his own. That is why he started to once again fully pursue objects, which again were the subjects of the character of the materials, but this time with the intention to underscore their tactile character. The objects that originated – tactile chairs, rolling pins, cutting boards and wooden spoons – designated for the touch of varied parts of the body, were supposed to activate the tactual knowledge and behaviour and release this human sense of utilitarianism. The objective was supposed to be an intensive exacerbation of the senses, emphasizing the significance of the sense of touch and arousing imagination. Švankmajer did not only use objects to achieve this, but also experiments during which he let members of the surrealistic group touch the structures he created while he recorded their word associations. Švankmajer compared the results of his touch experiments with visual perceptions and he compiled these into some sort of final reports, which he published in 1994 in the book Touch and Imagination (Introduction to Tactile Art) [Hmat a imaginace (Úvod do taktilního umění)].

Since the 1980s Švankmajer has been systematically pursuing, in addition to making “animal” creatures, also the production of collages and object assemblages and primarily making feature films (from the most recent ones we should mention Conspirators of Pleasure, 1996, Little Otik, 2000, Lunacy, 2005 and Surviving Life, 2010). In any of his activities he never ceases to place an emphasis on the concept of imagination and on the need for its continual activation. Švankmajer’s surrealistic motto “All power to imagination” did not become the slogan of the socialistic and squatter movement for no reason. It is not merely a simple peek into the fantastic world but rather an attempt to implement the possibility to change or to at least indicate it, because until a change (whether political, artistic, social or life) becomes conceivable, it will never happen.

Literature used: Dryje, František a Schmitt, Bertrand (ed.), Jan Švankmajer. Možnosti dialogu / Mezi filmem a volnou tvorbou, Arbor vitae, Řevnice, 2012.

- Author of the annotation

- Anna Remešová

- Published

- 2015

CV

Studies:

1954–1958

studying art creation / directing at the Department of Puppet Theatre, DAMU

1950–1954

High School of Art Industry, Department of Stage Design

AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS (selection):

2010

Czech Film Academy

won Czech Lion for the film Surviving Life for the Best Design Achievement

2009

Karlovy Vary International Film Festival

awarded with Special Crystal Globe for his lifetime achievements

2002

Czech Film Academy

won Czech Lion for the film Otesánek as the Best Czech Film

2001

Cracow Film Festival

awarded with Dragon of Dragons Prize for his lifetime achievements

1996

Locarno International Film Festival

nominated Golden Leopard for Conspirators of Pleasure

1995

Czech Critics Awards

won Christian for the film Faust as the Best Animated Film

1995

Czech Film Academy

won Czech Lion for the film Faust for the Best Design Achievement

1994

Karlovy Vary International Film Festival

won Special Prize of the Jury for the film Faust (tied with Przypadek Pekosinskiego)

1989

Annecy International Animated Filmfest

won the Feature Film Award for the film Alice

1984

Montreal World Film Festival

won Jury Prize (Short Films) for the film The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope

1983

Berlin International Film Festival

won Golden Berlin Bear for the film Dimensions of Dialogue

1969

International Short Filmfest Oberhausen

won Grand Prix for the film The Flat

1968

International Short Filmfest Oberhausen

won Prize of Marx Ernst for the film Historia Naturae

1966

International Filmfest Mannheim-Heidelberg

won Josef von Sternberg Award for the film Punch and Judy

- Member of art groups included in ARTLIST.

- Member of art groups not included in ARTLIST.

- Surrealistická skupina

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2015

Jan Švankmajer: Lidé, sněte! / Artinbox / Praha

Kunstkamera Jana Švankmajera / Museum Kampa / Praha

2014

Metamorfosi, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Centre de la Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona / Barcelona

Jan Švankmajer: Možnosti dialogu mezi filmem a volnou tvorbou / České centrum / Praha

2013

Jan Švankmajer: The Inner Life of Objects / University of Brighton Gallery / Brighton

Jan Švankmajer. Možnosti dialogu. Mezi filmem a volnou tvorbou / Muzeum moderního umění / Olomouc

2012

Jan Švankmajer / Kerstin Engholm Galerie / Vídeň

Jan Švankmajer. Survivre à sa vie, collages / Galerie les yeux fertiles / Paříž

Možnosti dialogu / GHMP, Dům U Kamenného zvonu / Praha

2011

Yume Koso makoto / České centrum / Tokio

Jan Švankmajer / Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions / Tokio

Das Kabinet des Jan Švankmajer. Das Pendel, die Grübe und andere Absonderlichkeiten / Kunsthalle / Vídeň

Jan Švankmajer – Eva Švankmajerová, Film a jeho okolí, společně s E. Švankmajerovou / Laforet Harajuku / Tokio

Jan Švankmajer – Eva Švankmajerová / Kyoto Bunka Hakubutsukan / Kjóto

2010

Přežít svůj život, koláže / Art in Box / Praha

2008

Jan Švankmajer / Aichi Arts Center / Nagoya

Salamandr, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Slovácké muzeum / Uherské Hradiště

2007

Jan Švankmajer: Human Chair (Ningen Isu) / České centrum / Tokio

Jan Švankmajer – Eva Švankmajerová / Laforet Harajuku / Tokio

2006

Jan Švankmajer: Alenka / České centrum / Tokio

Gaudia Evašvankmajerjan, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Niitsu Museum of Art / Niigata

2005

Gaudia Evašvankmajerjan, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / The Museum of Modern Art / Hayama

Syrové umění, sbírka Jana a Evy Švankmajerových / Galerie Klatovy/Klenová; Moravská galerie, Brno

2004

Eva Švankmajerová, Jan Švankmajer / Centre tchèque / Brusel

Jídlo, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Jízdárna Pražského hradu / Praha

Paměť animace – animace paměti, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Galerie města Plzně / Plzeň

2003

Memoria dell’animazione. Animazione della memoria, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Palazzo pigorini a Galleria San Ludovico / Parma

Mediumní kresby a fetiše, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Městské muzeum / Nová paka

Jan Švankmajer et Eva Švankmajerová / Galerie les yeux fertiles / Paříž

2002

Švankmajer E&J. Bouche à bouche, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Château-Musée, Annecy; Musée de la marionette, Charleville-Mézière

2001

Imaginativní oko, imaginativní ruka, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou ( Galerie Jiřího a Běly Kolářových / Praha

1998

Parakabinet, společně s E. Švankmajerovou / Galerie moderního umění / Hradec Králové

Anima, animus, animace, společně s E. Švankmajerovou / Galerie U Bílého Jednorožce, Klatovy / Centrum Egona Schieleho, Český Krumlov / Galerie moderního umění, Hradec Králové / Oblastní galerie Vysočiny, Jihlava / Východočeská galerie, Pardubice

1997

Přírodopisný kabinet, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Galerie Josefa Sudka / Praha

Mluvící malířství, němá poezie, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Obecní galerie Beseda / Praha

1996

Hmat, Arcimboldo a vanitas, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Londýn, Varšava a Krakov

1995

Athanor, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Telluride

1994

Hmat, alchymie a loutka / Středoevropská galerie / Praha

El llenguatge de l’analogie, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Sitges

1993

Das Lexicon der Träume / Kunstraum Freihaus / Vídeň

1992

Cyfleu breuddwydion. The Communication of Dreams, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Cardiff Chapter, The Davis Memorial Gallery / Newtown

1991

La fuerza de la imagionación / Valladolid

La Contamination des sens, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Centre International du Cinéma d’Animation / Annecy

1989

Film Retrospective / Museum of Modern Art / New York

1987

Bouillonnements cachés, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Brusel, Tournai

1983

Přírodopisný kabinet / Pražský filmový klub / Praha

1977

Infantile Lüste, společně s Evou Švankmajerovou / Galerie Sonnenring / Münster

1963

Objekty / Viola / Praha

1962

Kresby a tempery / Divadlo Semafor / Praha

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2012

Jiný vzduch. Skupina česko-slovenských surrealistů / Staroměstská radnice / Praha

2011

Surrealistická východiska (1948 – 1989). Odklony, návraty, přesahy / Letohrádek Hvězda / Praha

2008

Svět je strašlivý přírodopis / Prácheňské muzeum / Písek

Imaginace reality II / České centrum a Státní uměnovědný ústav / Moskva

2007

Černá a bílá jezera / Galerie Scarabeus / Praha

2004

Rodinný výlet s démony / Galerie Scarabeus / Praha

2003

Nalezený objekt redivivus / Galerie Concordia / Praha

2002

Příroda se nemýlí / Galerie Scarabeus / Praha

L’art brut tchèque / Galerie Halle Saint Pierre / Paříž

2001

Sféra snu 2001 / Sovinec

2000

Zábory, anexe, okupace, anšlusy / Galerie Zámeček / Příbram

Tschechischer Surrealismus und Art Brut zum Ende des Jahrtausends / Palais Palffy / Vídeň

1999

Svatokrádež. Zázračné proti posvátnému / Salmovský palác / Praha

1998

Invention, imagination, interpretation / Glynn Vivian Art Gallery / Swansea

1997

Jitro kouzelníků (Ztráty a nálezy) / Národní galerie, Veletržní palác / Praha

Očima Arcimboldovýma / Národní galerie, Veletržní palác / Praha

Surrealistická obraznost a kresba / Národní galerie, Palác Kinských / Praha

1995–1997

Z jednoho těsta / Semily, Cheb, Nitra, Brno, Praha

1994

Nebezpečné ozdoby / Lipnice nad Sázavou

1993

Sen, erotismus, interpretace / Slovenské kulturní centrum / Budapešť

Das Umzugskabinett / Galerie 13 / Hannover

1991

Sen, erotismus, interpretace (výstava Surrealistické skupiny) / Stredoslovanská galéria, Banská Bystrica / GHMB, Pálffyho palác / Galéria Médium, Bratislava

Třetí archa, 1979 – 1991. Surrealistická skupina v Československu / výstavní síň Mánes / Praha

1990

Analogon, 1969 – 1990. Voyage à travers les couleurs du temps / Galerie Neuf / Paříž

1984

Proměny humoru / Praha

1983

Sféra snu / Sovinec

1981

Exposition du Groupe surréaliste en Tchécoslovaquie / Galerie Phasme / Ženeva

1978

Le Collage surréaliste en 1978 / Galerie Le Triskèle / Paříž

1975

Armes et bagages / Galerie Verrière / Lyon

1968

Ausstellung tschechischer Künstler / Galerie Riehentor / Basel

1967

Fantasijní aspekty současného českého umění / Oblastní galerie Jihlava, Galerie Václava Špály v Praze

Prager Künstler / Galerie am Taubenmarkt / Linz

1966

Výstava mladých / Moravská galerie / Brno

1964

Skupina Máj / Nová síň / Praha

1961

4. výstava skupiny Máj / Poděbrady

- Collections

- Tate Modern v Londýně NG v Praze MU v Olomouci GVU v Chebu Galerie Klatovy/Klenová MG v Brně

Monography

- Monography

Vasseleu, Cathryn (ed.), Touching and Imagining. An Introduction to Tactile Art, I. B. Tauris, London/New York 2014.

Jiný vzduch. Skupina česko-slovenských surrealistů 1990 – 2001, Staroměstská radnice (katalog výstavy), Sdružení Analogon, Praha 2012.

Dryje, František a Schmitt, Betrand (ed.), Možnosti dialogu / Mezi filmem a volnou tvorbou, Arbor vitae, Řevnice 2012.

Castro, Eugenio – Lacalle, Julián (eds), Para ver, cierra los ojos, Filmoteca Nacional de Madrid, Pepitas de Calazaba, Madrid 2012.

Surrealistická východiska (1948-1989). Odklony. Návraty. Přesahy, Památník národního písemnictví (katalog výstavy), Společnost Karla Teiga, Praha 2011.

Jodoin-Keaton, Charles, Le cinéma de Jan Švankmajer. Un surréaliste animé, Rouge profound, Paris 2011.

Das Kabinet des Jan Švankmajer. Das Pendel, die Grübe und andere Absonderlichkeiten, Ursula Blickle Stiftung, Kunsthalle Wien, Verlag für Moderne Kunst 2011.

Gutiérrez, Gregorio Martín (ed.), Jan Švankmajer. La magia de la subversión, T&B editores, Madrid 2010.

Švankmajer, Jan, Frolcová, Milada, Salamandr. Výběr z tvorby Evy a Jana Švankmajerových, Slovácké muzeum, Uherské Hradiště 2008.

Akatsuka, Wagaki, Švankmajer to Čko áto, Michitani, Tokyo 2008.

Skupina Máj 57. Úsilí o uměleckou svobodu na přelomu 50. a 60. let, Císařská konírna (katalog výstavy), Správa Pražského hradu, Praha 2007.

Tsjechische L’art brut tchèque, Musée d’art spontané, Centre tchèque (katalog výstavy), Bruxelles 2004.

Otcovská, Květa a Frídlová, Olga (ed.), Jan Švankmajer. Transmutace smyslů, Středoevropská galerie a nakladatelství, Praha 2004.

Dryje, František a Stolařík, Bruno (ed.), Jídlo / Eva Švankmajerová, Jan Švankmajer, Arbor vitae, Správa Pražského hradu, Praha 2004.

Corbet Maurice, Vimenet Pascal (eds), Švankmajer, E&J – Bouche à bouche, Éditions de l’œil, Montreuil 2002.

L’art brut tchèque, Galerie Halle Saint Pierre (katalog výstavy), Paris 2002.

Dryje František (ed.), Síla imaginace. Režisér o své filmové tvorbě, Dauphin – Mladá fronta, Praha 2001.

Sféra snu 2001. Výstava Surrealistické skupiny v Československu, Galerie Sovinec, 2001 (katalog Analogon č. 32).

Imaginativní oko, imaginativní ruka, Galerie Jiřího a Běly Kolářových, Vltavín, Praha 2001.

Kumagai, Maki – Holý, Petr, Švankmajer no hakubutsukan, shokkaku geijutsu, obuje, koraju shu, Kokusho Kankókai, Tokio 2001.

Tschechischer Surrealismus und Art Brut zum Ende des Jahrtausends, Palais Palffy, Wien 2000.

Zábory, anexe, okupace, anšlusy. Výstava Surrealistické skupiny v Česko-Slovensku, Galerie Zámeček, Příbram 2000, (katalog Analogon č. 30).

Svatokrádež, Mezinárodní surrealistická výstava, Salmovský palác, Praha 1999 (katalog Analogon č. 25).

Akatsuka, Wagaki, Švankmajer no sekai, Kokusho Kankókai, Tokyo 1999.

Intervention, Imagination, Interpretation. A Retrospective Exhibition of the Group of Czech and Slovak Surrealists, Swansea Festval of Czech and Slovak Surrealism, Swansea 1998.

Očima Arcimboldovýma, Národní galerie (katalog výstavy), Praha 1997.

Surrealistická obraznost a kresba, Národní galerie (katalog výstavy), Praha 1997.

Švankmajerová, Eva a Švankmajer, Jan, Evašvankmajerjan: anima, animus, animace, katalog k výstavám v Klatovech, Českém Krumlově, Hradci Králové, Jihlavě, Pardubicích, 1997.

Hames, Peter (ed.), Dark alchemy. The Films of Jan Švankmajer, Flicks Books, Trowbridge 1995.

Švankmajer, Jan, Hmat a imaginace (úvod do taktilního umění). Taktilní experimentace 1974-1983, Kozoroh, Praha 1994.

Das Umzugskabinet. Ausstellung der Gruppe der tschechichen und slowakischen Surrealisten, Galerie 13 (katalog výstavy), Hannover; Galerie Forum, Gütersloh 1993.

Das Lexikon der Träume, Kunstraum Freihaus, Wien 1993.

Třetí Archa. Výstava Surrealistické skupiny v Československu, Galerie Mánes (katalog výstavy), Sdružení Analogonu a Lidové noviny, Praha 1991.

Het Iudicatief Principe, Antwerpse Film Stichting, Antwerpen 1991.

Analogon, voyage à travers les couleurs du temps. Exposition du Groupe surréaliste en Tchécoslovaquie, Galerie Neuf, Editions Hourglass, Paris 1990.

Vimenet Pacal, Alice. Écoles et cinéma, Les enfants du cinéma, Yellow Now, Paris 1989.

Bouillonnments cachés, tableaux, dessins, gravures, collages, céramiques, objets, films de Eva et Jan Švankmajer, Edition Confédération Parascolaire, Bruxelles et Tournai 1987.

Proměny humoru. Výstava Surrealistické skupiny v Československu, Sovinec, Praha, Editions Le La, Genève 1984.

Sféra snu. Výstava Surrealistické skupiny v Československu, Sovinec, Editions Le La, Genève – Prague 1983.

Exposition du Groupe surréaliste en Tchécoslovaquie, Galerie Phasme (katalog výstavy), Genève 1981.

Le collage surréaliste en 1978, Galerie Le Triskèle (katalog výstavy), Paris 1978.

Infantile Lüste, Galerie Sonnering, Münster 1977.

Armes et bagages, Galerie Verrière (katalog výstavy), Lyon 1975.

Skupina Máj – 5. výstava skupiny Máj, Nová síň (katalog výstavy), Praha 1964.