- First Name

- Milan

- Surname

- Dobeš

- Born

- 1929

- Birth place

- Přerov

- Place of work

- Bratislava

- Website

- http://www.milandobes.sk/

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

The Slovak artist Milan Dobeš is one of the most prominent representatives of the constructivist tendencies that were most apparent on the Czechoslovak art scene during the 1960s. Like other creators of objects from the generation of artists born in the 1920s, e.g. Karel Malich and Radoslav Kratina, Dobeš did not receive a classical training in sculpture. He studied figural and landscape painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bratislava. In his early, impressionistic landscapes and urban scenes we see his fascination with light and dynamic forms. During the 1950s he experimented with other spheres as well. In addition to the project Polymuzický prostor / Polymusical Space at Divadlo vidění (Theatre of Vision) he worked as stage designer and dancer in the experimental dance group Vysokoškolský umělecký soubor (University Art Ensemble).

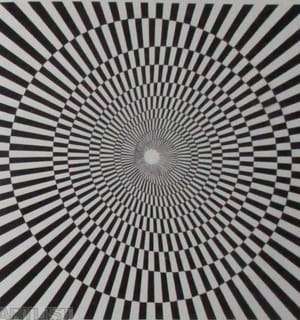

At the end of the 1950s, under the influence of Expo 58 in Brussels, Dobeš re-assessed his work to date and began to move slowly in the direction of geometric abstraction. At first he created geometric drawings, graphics and prints, in which the basic element was a circle and its segments, and this became the main feature of his later work. In the early sixties he finally turned his back on painting in favour of kinetic objects in the series Vizuálních objektů a mobilů / Visual Objects and Mobiles. His objects used either an external lights source, as in the series Pulsující rytmy / Pulsating Rhythms, or light was an integral part, e.g. the project Majáky / Lighthouses. He set forth his aesthetic in a manifesto from 1961 entitled O světle a pohybu / On Light and Movement. The title makes it clear which elements he now regarded as pivotal.

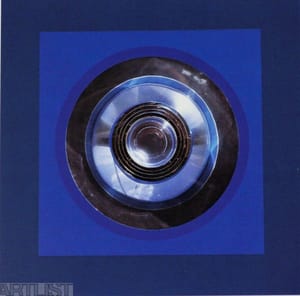

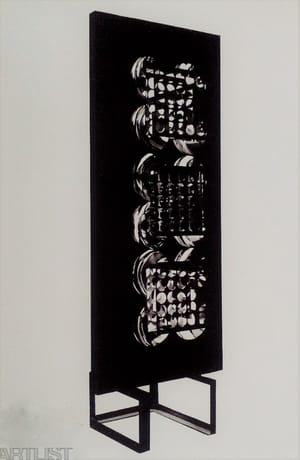

Unlike Czech representatives of constructivist tendencies, Dobeš’s approach was characterised by the inclusion of technical elements such as electrical motors, light bulbs and above all convex and concave mirrors. The use of reflection is reminiscent of the work of Hugo Demartini, whose objects never transcended the threshold of stability and whose movement remained only imaginary, introduced by means of the reflection and movement of the people in front of it. During the latter half of the sixties constructivism became one of the main directions in Czech art. The exhibition Nová citlivost / New Sensitivity of 1968, at which Dobeš was represented, was a kind of synthesis of variations upon constructivism. A feature of this new sensitivity was an admiration for technology and a neo-humanism, which turned away from nature and applied an individual style. Dobeš was something of an outlier at the exhibition, mainly because technique arose of its own accord in his works. In the exhibition catalogue he wrote: “Technique and science offer people the opportunity to avail themselves of more time to devote to themselves, philosophy and art. Civilisation helps put aside the spectacles of ingrained thinking and understanding in three-dimensionality.”

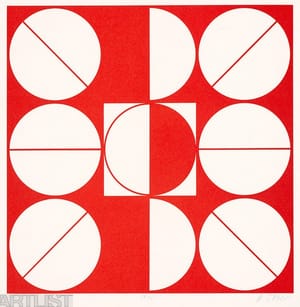

By involving the fourth dimension, i.e. movement, in his objects, Dobeš moved closer to events taking place on the global art scene, in which kinetic art was combined with op-art (as in the work of Julio Le Parc and Jesús Rafael Sot). In addition to spatial works, drawings and silk-screen graphics were an important part of his work during this period, creating optical illusions and the semblance of movement through geometric composition. This gave rise to objects characterised by rotary movement drawing on the primary colours, e.g. Kruhy a světlo / Circles and Light (1967) or Barevná rytmická světla / Coloured Rhythmical Light (1965). Dobeš was soon receiving international recognition, and this was aided by the Prague exhibition Vizuální a kinetické objekty / Visual and Kinetic Objects of 1966. In the following years he participated at several international exhibitions, the most important being 4. dokumenta in 1968 and EXPO 70 in Osaka, where he exhibited the object Hra světla a tvarů / The Play of Light and Shapes.

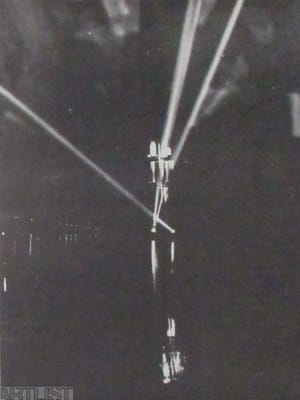

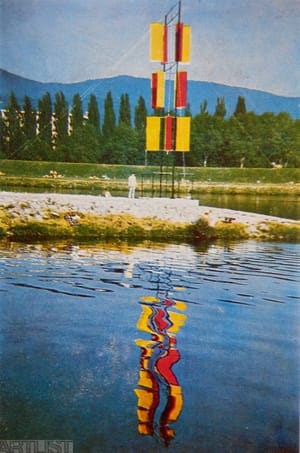

Dobeš made the most of technical possibilities and in the 1970s returned to art and theatre in a kinetic performance of Polymuzický prostor in Piešťany in 1970. In the same year and place he created the object Kinetická věž / Kinetic Tower, which was moved by wind in the manner of Alexander Calder. During the seventies, at the start of the normalisation period, Dobeš was able to travel to the USA, where in 1971 he toured with the American Wind Symphony Orchestra and accompanied his light-kinetic programme with symphonic works by Toshiro Mayuzumi and Krysztof Penderecki.

In 1973 he set forth his aesthetic programme in a text entitled Světlo jako výtvarný materiál / Light as a Creative Material. Given the huge restrictions placed on exhibiting at this time, he devoted himself to more intimate sculptures, optical graphics and collages. From the end of the sixties he had also had the opportunity to create monuments, something he did mainly for towns and cities in Slovakia. True to their creator’s admiration for technology, these objects were made of glass, plastic or metal. The most important include the kinetic object in Montevideo (1969), the light-kinetic object in the building of the Czechoslovak Embassy in Stockholm (1972), and the optical relief in the entrance hall of the Czechoslovak Science and Technology Societies in Bratislava (1979).

During the 1980s he continued to develop his creative principles, for instance in the series Opticko-kinetických objektů / Optical-Kinetic Objects. He also worked on graphics, where the main role was again taken by the circle and variations thereon, e.g. Pohyb struktur / The Movement of Structures (1986). In 1988 he wrote his second artistic manifesto entitled Dynamický konstruktivismus / Dynamic Constructivism, in which he writes: “Movement is the basic condition of the existence of everything. Movement is life. To depict movement is to depict life.”

In 2001 the Milan Dobeš Museum was founded, which houses not only works by Dobeš but also by those close to him in the spirit of constructivism and op-art, such as Victor Vasarely, Karel Malich and Radoslav Kratina. In 2016 a Milan Dobeš Museum was opened in Ostrava, at which the artist himself participated.

- Author of the annotation

- Zuzana Krišková

- Published

- 2018

CV

Sudies:

1951–1956Vysoká škola výtvarných uměni v Bratislavě, Ladislav Čemický, Bedrich Hoffstädter

Awards:1970 I. cena, Arts Festival Marietta, Ohio

1970 I. cena, Socha piešťanských parkov, Piešťany

1969 I. cena, Sochařské bienále, Montevideo

- Member of art groups not included in ARTLIST.

- Jiná geometrie

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2009

Gálerie Komart, Bratislava

Na vlnách konstruktivismu/On the Wawes of Constructivism, Ostrava

2008

Galerie Zdeněk Sklenář, Praha

2005

Priestory Hoechst-Biotika, Martin

Museum of cotemporary art, Zagreb

2004

Galéria umenia, Nové zámky

2003

Galéria mesta Bratislava, Bratislava

Museum Kampa, Praha

Galerie Lindner, Wien

2001

Múzeum Milana Dobeša (otvorenie múzea)

2000

CC centrum, Bratislava

1999

Muzeum J.A.Komenského, Přerov – zámok (pri príležitosti umelcových 70.narodenín)

1998

Hotel Perugia, Bratislava

1997

Galéria Z., Bratislava

Galéria Slovenskej sporiteľne, Bratislava

Hypobank, Bratislava

1996

Moravská galerie, Brno

1995

Slovenská národná Galéria, Bratislava

Muzeum J.A.Komenského, Přerov-zámok

1994

Umelecká beseda slovenská, Bratislava

1993

Štátna Galéria, Banská Bystrica

1990

Sieň Laca Novomeského, Braislava

Gallery Mitte, Wien

1989

Dom slovenskej kultury, Praha

Gallery Verena, Zurich

1986

Československé kultúrne stredisko, Havana

1984

Výstavný pavilón Datasystém, Brno

1982

Muzeum J.A.Komenského, Přerov – zámok

1972

Charter Oaks Galler, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania

1971

Point park College Gallery, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania

Hudson River Museum, New York City

Memorial Hall Gallery, Penna, California

AWSO Gallery,Oakmont (Pennsylvania), New Martinsville

Parkersburg, Ravenswood (West Virginia), Marietta (Ohio), Aschland (Kentucky)

1966

Galéria domu SČSSP, Praha

1965

Galéria Cypriána Majerníka, Bratislava

1958

Galéria mladých, Bratislava

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

Výběr:

2017

ČS koncept 70. let/ CS Conceptual Art of the 70s, Faith Gallery, Brna

Příliš mnoho zubů, Museum Kampa, Praha

2016

Kunst in Europa 1945–1968, Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, Karlsruhe

XXL pohledů na současné slovenské výtvarné umění, Galerie Středočeského kraje, Kutná Hora

2015

Konkret/ism 1967–2015: Výstava KK3 Klubu Konkretistů, Topičův salon, Praha

2012

Od Tiziana po Warhola: Muzeum umění Olomouc, Olomouc

Milan Dobeš a evropská grafika, Galerie Závodný, Mikulov

2011

Papier kole – slovenská koláž XX. a XXI. Století, Galerie Smečky, Praha

Dialog přes hranice – Sbírka Hanse Petera Rieseho, Galerie Středočeského kraje, Kutná Hora

Současná slovenská geometrie 2, Galerie města Plzně, Plzeň

2010

Hugo Demartini a Milan Dobeš: Světlem-prostorem-pohybem, Brno Gallery CZ, Brno

2009

Mit konkreter Kunst leben, Gesellschaft Künst und Gestaltung, Bonn

2008

Art Beijing 2008, National Agricultural Center, Peking

Mezinárodní trienále současného umění 2008, Veletržní palác, Praha

Pohyb jako poselství, Národní Galerie, Praha

České a slovenské výtvarné umenie 60. rokov 20. storočia, Galéria M.A. Bazovského, Trenčín

20.století ve slovenském výtvarném umění, Jízdárna – Pražský hrad, Praha

1960 – súčasnosť, Sloveské umění plus čeští hosté, Galerie hlavního mesta Prahy, Dúm

u zlatého prstenu

2007

Prague Biennale 3 – Global and Outsiders: Connecting Cultures in Central Europe, Karlínská hala, Praha

Sme svoji, Vyběr současného slovenského umění, Muzeum v Bruntále, Zámek

„Op art“ schrin kunsthalle, Frankfurt

„Ferne nahe“, Zyklus 2, Slowakei, Lilienfeld

Praguebiennale 3, Karlín Hall, Praha

„Hommage á Kassák“, Kassák Múzeum , Budapešť

Slovenská grafika 20.storočia, Galéria mesta Bratislavy

2006

Sztuka optyczna i kinetyczna zo zbiorów museuchelmskiego, Chelm

Evropsky neokonštruktivizmus 1930 – 2000, Moskovské múzeum súčasného umenia, Moskva

Die neue tendenzen eine Europaische kunstler bewegung 1961 – 1973, Museum fur

konkrete kunst, Ingolstadt

2005

Filoluce – Da balla a boeti, Da fontana a flavin, Museo della permanentne,Milano

Pražské bienále 2, Karlínska prumyslová Hala, Praha

2004

Ejhle světlo/Look Light, Moravská galerie v Brně, Brno

2002

Objekt-objekt: Metamorfózy v čase, Pražákův palác, Brno

2001

Jiří Kolář sběratel, Veletržní palác, Praha

1999

Akce, slovo, pohyb, prostor – experimenty v umění šedesátých let, Městská knihovna Praha, Praha

1995

Nová citlivost, Pražákův palác, Brno

Zeit genössiche Kunst aus den Europäischen osten (Sammlung Jürgen Weichardt) Landes

Museum Oldenburg

Prekročenie hraníc (1964–1971), Považská galéria, Žilina

Šesťdesiate roky v slovenskom výtvarnom umení, Slovenská národná galéria, Bratislava

Portfolio protagonistov. 55 protagonistov konštruktívneho umenia, Ľubľana

1994

Súčasná slovenská grafika, Budapešť

Zwischen Zeit und Raum I. (Tendenzen Mitteleuropäischer Kunst – in den 60er bis 80er

Jahren, Teil I., Konstruktiv), Galerie Schoppenhauer, Kolín

Zrcadlení, Galerie R, Praha

Nová citlivost, Galerie výtvarného umění, Litoměřice

Náš kinetizmus 60. let, Galerie ‘60/’70, Praha

Rozpamätávanie, Galéria mesta Bratislavy, Mirbachov palác, Bratislava

Nová citlivost, Moravská galerie Brno, Olomouc

1993

Poesie racionality, Valdštejnská jízdárna, Praha

1992

Svetová výstava EXPO ‘92, Sevilla

Kassak – Homage a Lajos Kassak 100, SNG, Bratislava

Wegzeichen/Zeitgenössische Slowakische Kunst, Osteuropäisches Kulturzentrum, Kolín

Zwischen Objekt und Installation / Slowakische Kunst der Gegenwart, Museum am Ostwall,

Dortmund, 1993

Elektráreň T, Tatranská galéria, Poprad

Múzeum moderného umenia rodiny Warholovcov, Medzilaborce

Priestor ‘93, 13. ročník výstavy Socha piešťanských parkov, Piešťany

Súčasná slovenská grafika

1991

Sen o múzeu, Považská galéria, Žilina, Moravská galéria, Brno

Slovenské výtvarné umenie a hudba, Galéria Júliusa Lörincza, Dunajská Streda

Iná geometria, Galéria Gerulata, Bratislava

Jiná geometrie, Mánes, Praha

Súčasné slovenské výtvarné umenie, Európsky kultúrny klub na Slovensku, Bardejov

Hýbače, Galéria Gerulata, Bratislava, Východoslovenská galéria, Košice

Členská výstava sdružení Q, Dom umenia, Brno

Kinetické variabilní umění, Národní technické muzeum, Praha

1990

Konstruktivní tendence šedesátých let, Středočeská galerie, Praha

Pocta umělců Jindřichu Chalupeckému, Městská knihovna Praha, Praha

1983

Monumentální tvorba na Slovensku, Dom kultúry, Bratislava

1980

Die Kunst Osteuropas im 20. Jahrhundert, Garmisch-Partenkirchen

1970

Socha piešťanských parkov, Piešťany

1969

Arte contemporanea in Cecoslovacchia, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Řím

Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo

1968

Nová citlivost. Křižovatka a hosté, Mánes, Praha

Konstruktive Tendenzen aus der Tschechoslowakei, Altstadtmuseum Fembohaus, Nürnberg

1967

Mostra d’Arte contemporanea cecoslovacca, Castello del Valentino, Turín

1963

Súčasné slovenské výtvarné umenie, Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

1958

Umění mladých výtvarníků Československa 1958. Obrazy a plastiky, Dům umění města Brna, Brno

- Collections

- Galéria města Bratislavy Galerie Benedikta Rejta Hudson River Museum Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires Museum Folkwang Národní galerie v Praze Slovenská národná galéria

Monography

- Monography

Milan Dobeš, ed.: Jozef Ruttkay, Bratislava 1994 MAURERY M.: Milan Dobeš: Medzi pohybom a svetlom, magisterská diplomová práce, Masarykova Univerzita, Brno 2016 JÚZA J.: Milan Dobeš: Pulsing emotions, katalog výstavy, Ostrava 2009 HLAVÁČEK J.: Neokonstruktivismus a kinetismus, in: České dějiny výtvarného umění IV/1, 1958–2000, Praha 2007, 207–220 HAVRÁNEK V.: Kinetické umění, in: Akce, slovo, pohyb, prostor: experimenty v umění šedesátých let, GHMP, Praha 1999, str. 64 – 111 HLAVÁČEK J.: Poezie racionality, České muzeum výtvarného umění, Praha 1993 HLAVÁČEK J.: Jiná geometrie, katalog výstavy, Mánes, Praha 1991 PADRTA J.: Nová citlivost, katalog výstavy, Mánes, Praha 1968

- Articles

KLIVAR M.: Kinetické umění v architektuře, in: Československý architekt, 1990, č. 2, s. 8 KOSTROVÁ Z.: Rozhovor s Milanem Dobešem o Bienále sochárstva ve volnej prírode v Montevideu, in: Výtvarná práce, 1979, č. 25–26, str. 1, 6 KONEČNÝ D.: K současnému stavu a perspektivám kinetismu a umění nové reality u nás, in: Acta scaenographica VI, 1966, č. 11, s. 219 – 220. CHALUPECKÝ J.: Milan Dobeš, in: Výtvarná práce XIV, 1966, č. 16, s. 5

- Personal texts not included in database

O dynamickém konstruktivismu, 1988 Světlo jako výtvarný materiál, 1973 O světle a pohybu, 1961