- First Name

- Stanislav

- Surname

- Judl

- Born

- 1951

- Birth place

- Plzeň

- Died

- 1989

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

The work of Stanislav Judl, a significant part of which was created during only ten years, is an important contribution to Czech art of the eighties. Although the year of his birth puts the artist in the 12.15 generation (during his studies for instance he encountered Petr Pavlík, Vladimír Novák, Václav Bláha and Michael Rittstein, all of whom had previously studied at the Paderlík Atelier; Ivan Kafka, another member of 12.15, is a year younger), apart from a short early period of grotesque figuration he has little in common those figures. On the contrary his work evinces several traits in common with the postmodern generation of the eighties, though in its gravitation toward transcendental values it goes beyond this too. Judl has traditionally been allocated an interstitial position within the context of Czech art. He is a creative loner in the mould of Václav Stratil, Margita Titlová, Josef Žáček and Petr Veselý.

At school and for a time afterwards Judl earned nothing from conventional period production. He painted pictures in the spirit of children’s illustrations of the time. More personal motifs gradually crept into this undemanding iconography, e.g. references to the mechanically manipulated person (Mechanical Man, 1979-80). A key work marking a departure from his early period is the oil-on-plywood Schizophrenia (1979). Its two parts – on the left a childishly conceived cat and paper swallows, on the right a monochrome crimson surface – are separated by a brutal chasm symbolising the watershed in his work. The period already mentioned of grotesque pictures follows, the titles of which often feature a play on words (Linguist, Waiting for the Day which Never Comes, Choke /by Soul/; Wholesale with Small Goods).

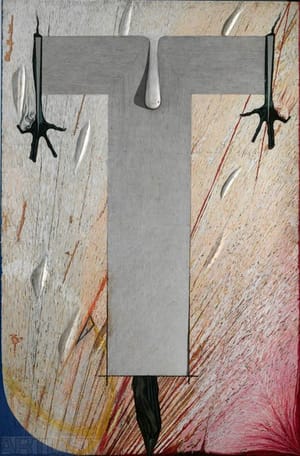

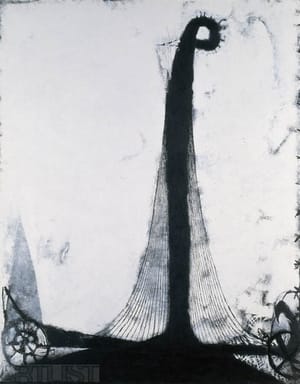

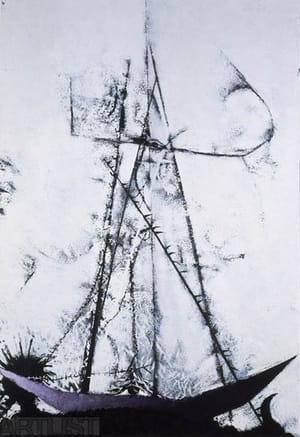

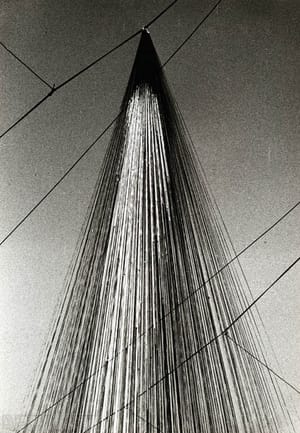

Judl was already caught up in the circle of unofficial art at this time. He participated in two important events which took place outside galleries and were broken up by the police without viewers being able to see their results: the meeting on tennis courts in the grounds of Sparta, Prague in June 1982, and the Chmelnice symposia at Mutějovice in autumn 1983. At the second event he created the installation Lacetka, named after the textile ribbon. A subtle linear cone was hung by its tip on one of the wires between the columns of a hop garden, thus creating a direct optical link with the sky as a symbol of a transcendental sphere. The same motif, combined with a silhouette of a stretched out figure, then plays a key role in the series which he entitled Grey Pictures (1983-84). Both sharp and unfocussed lines of various intensities of black on a white background “soiled” by unclear traces and frequent other nuances create a rich visual structure to these pictures.

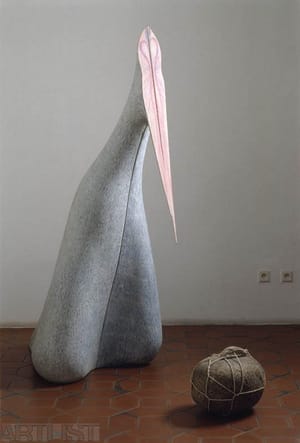

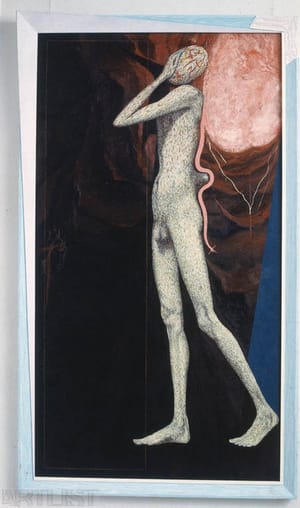

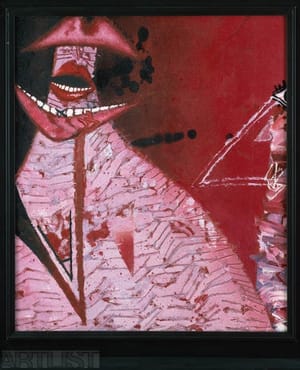

The experience of the Mutějovice symposium meant a definitive decision for Judl that experimental procedures expanding the sphere of art beyond its traditional boundaries did not correspond to his plans and objectives. On the contrary, the central theme which he proceeded to examine both in his artwork and his thoughts was the historical transformation of the traditional hung picture, the loss of its aura, and the possibility of reclaiming this sacred dimension. If in the Grey Cycle motifs appear which assign it a place within the first archetypal layer of Czech postmodernism (boat, cultish cart, meander), he adopts a critical stance to the following series of wild painting linked with wordplay, banality and empty meaning. On the contrary, he “enters territory which had been more or less taboo for artists of the twentieth century: the question of the existence of God.” (P. Pečinková). He found the inspiration to consider the relationship of the terrestrial and the absolute in the baroque, especially in the study by Zdeněk Kalista entitled The Face of the Baroque (which was published in Munich in 1982 in the Testimony edition). He attempts to return a sacred function to the picture, a feature highlighted not only by the titles chosen (Sanctuary, Martyr, Madonna, Saint in a Hat), but also by certain formal characteristics (unconventional frames, the Ark triptych conceived of as a winged altar). Pictures based on a phantasmagorical imagination and the techniques of the old masters are conceived of as a postmodern allegory. Alongside a preoccupation with the baroque, their complex iconography reflects an interest stretching back many years in heraldry, which Judl was involved in on a virtually professional level. In his last period he examined the theme of death, which interested him as a timeless topic which art had always confronted. And death finally caught up with him: in 1989, shortly before his own solo exhibition prepared for the Railway Workers’ Central Cultural House in Prague, he committed suicide for reasons still unknown.

Though Judl was a man without faith or personal religious experience, the questioning of the absolute became the main theme of his output. Although this cut him off from the main currents of Czech postmodernism, Pavla Pečinková in a monograph on Judl says that “his symbolist visions make him far more postmodern than anyone (including himself) suspected at the time...”. He drew on the entire range of postmodern techniques, such as paraphrase, quotation and allegorical reinterpretation, though he stands in opposition “to their deliberate indifference to meanings and did not abandon the modernist concept of art as reaching out to the absolute. One of the most important aspects of our postmodernism was the rejection of the moral aspects of art, the very aspect which Judl so doggedly insisted on.”

- Author of the annotation

- Marcel Fišer

- Published

- 2010

CV

Studies:

1970-76 Academy of Fine Arts, Prague, studio of Arnošt Paderlík

1966-70 Secondary School of Applied Arts, Prague

Awards:

1973 Cena 17. listopadu, pro posluchače Akademie výtvarných umění v Praze

1976 Cena 17. listopadu, pro posluchače Akademie výtvarných umění v Praze

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2009

Stanislav Judl 1951-1989. Galerie U Bílého jednorožce, Klatovy, Galerie Klatovy / Klenová

2006

Stanislav Judl. Obrazy, kresby. Galerie v kostele sv. Marka, Kulturní dům města Soběslav

2001

Stanislav Judl. Západočeská galerie v Plzni (katalog Pavla Pečinková)

1989

Stanislav Judl. Ústřední kulturní dům železničářů, Praha (katalog Ivo Janoušek)

1987

Převážně obrazy. Atrium, Praha (katalog Petr Wittlich)

1986

Stanislav Judl. Ústav makromolekulární chemie ČSAV, Praha (katalog Pavla Pečinková)

1985

Stanislav Judl. Galerie v podloubí, Olomouc (katalog Pavla Pečinková)

1982

Stanislav Judl. Ústav makromolekulární chemie ČSAV, Praha (katalog Roman Prahl)

1981

Ivan Kafka - Stanislav Judl. Muzeum hrnčířství, Kostelec n. Č. lesy (katalog Roman Prahl a Marie A. Černá)

1979

Stanislav Judl. Muzeum hrnčířství, Kostelec n. Č. lesy

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2012-2013

Od Tiziana po Warhola: Muzeum umění Olomouc 1951-2011 (IV. Výtvarné umění 1948-2011), Trojlodí, Olomouc

2008

Autoportrét v českém umění 20. a 21. století / Self-portrait in the Czech Art of the 20th a 21st century, Alšova jihočeská galerie, hlavní sál, Hluboká nad Vltavou

Nechci v kleci! / No cage for me!, Muzeum umění Olomouc, Olomouc

2005

Exprese / Expressiveness, České muzeum výtvarných umění, výstavní prostory, Praha (Prague)

2004

Kresba, kresba... Česká kresba 80. let 20. století ze sbírek členských galerií RG ČR, Výstavní síň Masné krámy, Plzeň (Pilsen)

2003

Minisalon, Centre tchèque Paris (České centrum Paříž), Paříž (Paris)

2002

Minisalon, Majapahit Mandarin Hotel, Surabaya

Minisalon, Museum Puri Lukisan, Ubud

Minisalon, Galeri Nasional Indonesia, Jakarta

2001

Bilance II. Galerie umění, Karlovy Vary

2000

100+1 uměleckých děl z 20. století. České muzeum výtvarných umění, Praha

1997

Něco s osudem. Galerie umění, Karlovy Vary

1996

Barvy století. Galerie umění, Karlovy Vary

V prostoru 20. století. Galerie hlavního města Prahy

Umění zastaveného času. České muzeum výtvarných umění, Praha

1994

Příběhy bez konce. Moravská galerie, Brno

Záznam nejrozmanitějších faktorů. Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

1992

Reklama na nekonečno. Národní galerie, Praha

Minisalon. Jazzová sekce, Nová síň, Praha

1991

Šedá cihla. Galerie Klatovy - Klenová

1989

Střední věk. Galerie hlavního města Prahy, Oblastní galerie výtvarného umění Gottwaldov

1988

Jeden mladší, jeden starší. Lidový dům, Praha

Přírůstky. Galerie hlavního města Prahy

1987

Rockfest. Palác kultury, Praha

1984

Objekt a obraz. Bechyňská brána, Tábor

Možnosti dotyku. Městské kulturní středisko, Rokycany

1983

Prostor, architektura, výtvarné umění. Ostrava, Černá louka (nerealizováno)

Archeologické pamiatky a súčasnosť. Bratislava

Člověk a svět. Oblastní galerie Liberec

Archeologické pamiatky a súčasnosť. Bratislava

1982

Architekti, malíři, sochaři. Ústav makromolekulární chemie ČSAV, Praha

Od kresby k prostoru. Muzeum dělnického hnutí, Semily

Setkání na tenisových dvorcích. Areál Sparty, Praha

Mladí výtvarní umělci III. sjezdu SSM. Výstava z výsledků tvůrčích pobytů v průmyslových a zemědělských závodech. Malá galerie Československého spisovatele, Praha

Staroměstské dvorky. Praha (nerealizováno)

1981

Táborské setkání. Muzeum husitského revolučního hnutí, Tábor

1980

Setkání. Ateliér Petra Kováře v Podolí, Praha

1979

Výtvarní umělci dětem. Výstavní síň Mánes, Praha

- Collections

- Národní galerie v Praze Galerie hlavního města Prahy České muzeum výtvarných umění, Praha Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny Galerie výtvarného umění Roudnice n. Labem Galerie umění Karlovy Vary Západočeská galerie v Plzni Galerie Klatovy / Klenová

- Other realisations

1992 Kněžiště modlitebny evangelického sboru v Benešově 1988 Stěna v depu železničních vagonů ČSD, Praha 1977 Dekorativní stěna Stadionu E. Rošického, Strahov, Praha (s Rostislavem Novákem) Performace, Akce: 2010 Stanislav Judl: Slavnostní prezentace monografie, Café Jednorožec, Klatovy 1984 Možnosti dotyku, Výstavní síň MKS Rokycany, Rokycany

Monography

- Monography

Pečinková, Pavla: Stanislav Judl. Galerie Klatovy / Klenová 2009.

- Articles

Pavel Kácha: Škola, praxe, umění. Svobodné slovo, 18.12. 1983 Pavla Pečinková: Stanislav Judl. Příspěvek v ineditním sborníku NN 4, 1986, nestránkováno (s. 17-18) ach: Málo známé dílo. Lidová demokracie 26. 3. 1987 kli: Generační konfrontace výtvarníků. Lidová demokracie 15.11. 1988 pak: Jeden starší, jeden mladší. Svobodné slovo 1ý.11. 1988 Ivo Janoušek: Obrazové vize Stanislava Judla. Ateliér, 1989, č. 6 s. 5 Pavla Pečinková: Něco s osudem. Ateliér, 1990, č. 2, s. 5 Pavla Pečinková: Contemporary Czech Painting. Gordon&Breach, UK, 1993, s. 50-53 Jindřich Chalupecký: Nové umění v Čechách. H+H, Praha 1994, s. 150 Marie Judlová: heslo v NEČVU, UDU AVČR, Praha 1995, s. 329 Jiří Fiala: Mluví-li duše. Vesmír 1996, č. 5, s. 298-300 Zakázané umění I a II, Výtvarné umění 1995, č. 3-4; 1996, č. 1-2 Pavla Pečinková: Zlatá střední cesta. Sborník symposia Centrum – okraj ? Elita – priemer. Errata, Trnava 1999, s. 43-51 Splátka na dluh. Torst, Praha 2000, s. 58-61 Václav Malina: Setkávání se Stanislavem Judlem. Spektrum, 4, 2001, č. 3, s. 12 Pavla Pečinková: Stanislav Judl. Ateliér, 14, 2001, č. 19, s.4 Speciální číslo časopisu Pěší zóna věnované S. Judlovi: Pěší zóna, revue pro památkovou péči, archeologii, historii a umění, Plzeň, roč. 2001, č. 9 Marie Klimešová: Osamocený romantik Stanislav Judl. Revue Art, 2005, č. 2, s. 44-47 Peter Kováč: Judlova malířská cesta ze tmy ke světlu. Právo, 19, 2009, č. 88, s. 14