- First Name

- Theodor

- Surname

- Pištěk

- Born

- 1932

- Birth place

- Prague

- Place of work

- Prague

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

It is a generally known fact that Theodor Pištěk comes from an acting family. His father was the famous actor Theodor Pištěk and his mother Marie Ženíšková was also an actress. During the time of the Austro-Hungary Empire her father was the representative of the car maker Ford in Vienna and he also had the first airplane business. And his father was painter František Ženíšek – famous painter of the Czech renaissance and the author of the first curtain in the National Theatre in Prague. It is as if Theodor Pištěk utilized the talent and professions of all his predecessors in his art career. In addition to painting, he works with film and theatre, and the dominating subject of his paintings is the world of automobiles. Pištěk himself was also the Czechoslovakian representative in automobile races until the year 1973.

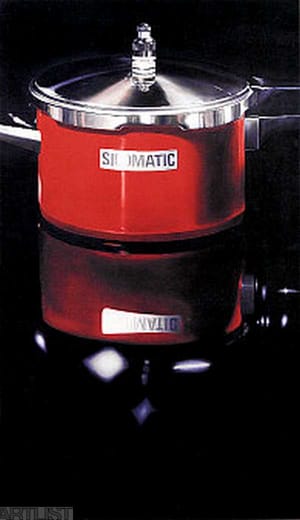

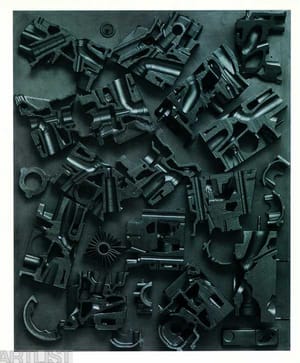

His initial work from the first half of the 1960s is filled with assemblage objects that represent Pištěk’s first significant entry onto the art scene. As an automobile enthusiast he used to visit auto body shops and he was ensorcelled by technical auto scraps. For example, that is how the series of reliefs made from cut up radiators (e.g. Kudy kam (All Adrift), 1962) came about. In some reliefs the composition evokes a poetic allusion to reality (Leť, motýlku, leť (Flight, Butterfly, Fly)), in other objects the playfulness with associations disappears. The material is simply piled up on the base in a way that the final image does not evoke any poetic or imaginative ideas (like at the group Šmidrové). Here Pištěk’s work resembles the aesthetics of the French Neuveau Realisme movement, for example.

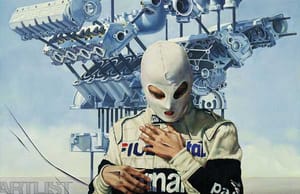

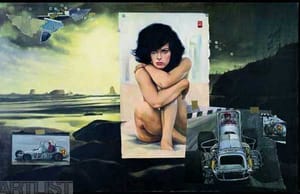

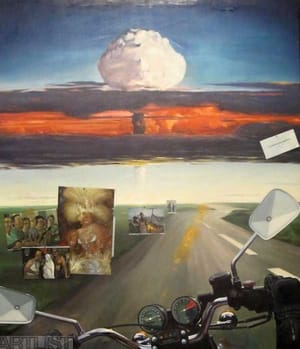

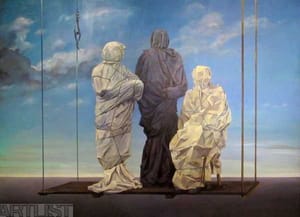

He started to pursue painting in the middle of the 1970s. He became the Czech representative of hyperrealism. His paintings were characteristic for their virtuoso drawing style and perfectly smooth paint, which was unusual in our environment at that time. Hyperrealism was a direction that was culminating in the United States on the break of the 1960s and 1970s. Pištěk’s approach was not exactly the same, however. His painting style was expanded by various meaning overlaps. American strict photorealism was about clean depiction of what we see. During his lifetime Pištěk painted only a few canvases (e.g. Zátiší s lampami (Still Life with Lamps) and Pocta Paipnovi (Salute to Paipen) that were in the sense of American hyperrealism. In most cases his work was a European version of it, enriched by his imaginative seeing of reality and surreal moments casting doubt on reality. For example, in the painting Krajina s Hondou (Landscape with a Honda) we see the view of a landscape over motorcycle handlebars, the landscape is fringed with different paintings and there is a nuclear explosion on the horizon. The dominating element in the painting Ecce Homo is the figure of a car racer in a racing suite with a mask; there is some kind of a sci-fi machine growing in the background and if we take a closer look we realize that the hands of the racer (Kristus v kombinéze (Christ in a Race Suit)) are cut open. On the painting there are also traces of whipping that cut the canvas. Pištěk is playing here with small illusions – from a distance it seems that the canvas is actually cut, but from up close we can see this is done with masterful painting skills. In some of his paintings we can see Pištěk’s obvious interest in three-dimensional space. For example, in the painting Tichá krajina (Silent Landscape) one would presume at first sight due to the artist’s hyperrealism scope that everything is painted. With a closer observation, however, we find out that the wire mesh in the front of the painting is real.

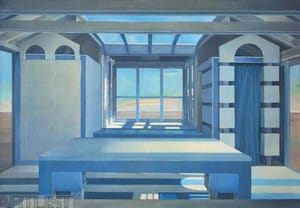

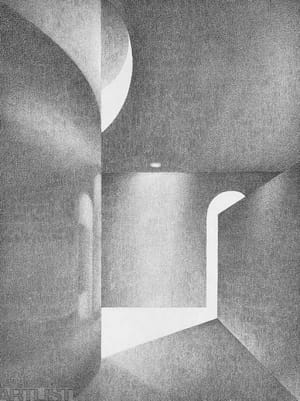

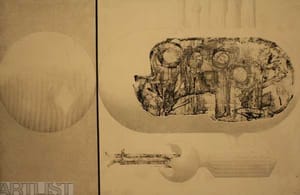

Although Pištěk is primarily famous for his photorealistic, figural paintings, he was also interested in abstraction and the developing of geometric morphology. He started experimenting with this in his early works already, which is manifested, for example, in the strictly abstract painting from 1971 Bez názvu (Untitled), but also in the later painting Léto (Summer) (1997). His ink drawings Kde budu žít příště (Where I Will Live Next) (1982), as well as his later painting depicting “depleted spaces” Poslední večeře (The Last Supper) (1983) are also developed in a geometric tone. This is about the capturing of abandoned spaces where nothing is happening. We can sense a human trace here and the entire scene has an imaginary dimension. Pištěk comments these works: “As a young boy, about ten years old, I was walking through Prague on a Sunday. It was not like it is today. I didn’t meet anyone in the morning. A completely abandoned city. When I looked through a gap between buildings, the horizon refracted and above it looked like something had ended and there was only the sky”.

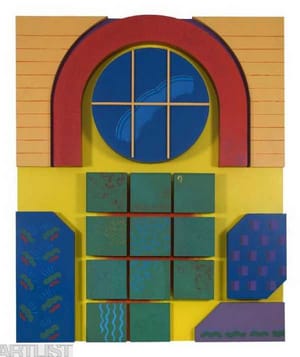

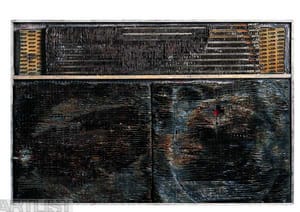

In the 1980s Pištěk entered the third dimension again and started to make installations, objects and reliefs. These include, for example, the geometric relief composition Variace na dané téma (Variation on a Given Topic) (1998) or the voluminous spatial installations that Pištěk presented at his exhibition in the Prague City Library (GHMP, 1997). In his last retroactive exhibition in the National Gallery he also presented the return to his beginnings: objects constructed from remodelled motor and radiator parts Termitiště, Brouk, Hlava Medusy a Bart Simpson (Termitarium, Beetle, Medusa’s Head and Bart Simpson).

The wider public knows Theodor Pištěk primarily as a costume artist. His cooperation with film producers dates back to ancient history: in 1959 he participated on František Vláčil’s film Holubice (Dove) and this cooperation continued in the 1960s in Vláčil’s films Markéta Lazarová, 1967, or Údolí včel (Valley of the Bees),1967. He also created costumes for the movie Tři oříšky pro Popelku (Cindarella) or the TV series Arabela. The highlight of his fame was working with Miloš Forman and receiving an Oscar for his costumes in the film Amadeus. He is also the holder of a Caesar for his costumes for the movie Valmont, he has a Czech Lion for his artistic contribution to the Czech film and he received a Crystal Globe at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival for his exceptional contribution to the world cinematography.

- Author of the annotation

- Ivona Raimanová

CV

Studies:

1952-1958 Academy of Fine Arts Prague, Vratislav Nechleba

1948-1952 Secondary School of Applied Arts, Prague

Awards:

2013 Křišťálový glóbus za mimořádný přínos světové kinematografii

2003 Český lev za umělecký přínos českému filmu

2000 vyznamenání prezidenta republiky Medaile za zásluhy

1990 - Cena Francouzské Akademie „César“ za kostýmní návrhy k filmu Valmont (Miloš Forman)

1984 Oscar za kostýmy k filmu Amadeus (Miloš Forman)

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2013

Theodor Pištěk, White Gallery, Osík (u Litomyšli)

2012

Kde budu žít příště, Galerie města Plzně, Plzeň

Ecce Homo, Veletržní palác, Praha

2007

3x Theodor Pištěk. Díl 1., Museum Kampa, Praha

3x Theodor Pištěk. Díl 2., Museum Kampa, Praha

3x Theodor Pištěk. Díl 3., Museum Kampa, Praha

2006

Obrazy / Paintings, Galerie umění Karlovy Vary, Karlovy Vary

2006

Pod povrchem, Galerie Montanelli, Praha

2003

Prostory 90´ / The Spaces 90´, Galerie Pecka, Praha

2000

Obrazy, České centrum Kyjev

1997

Práce z let šedesátých až devadesátých, Městská knihovna, Praha

1993

Theodor Pištěk, Schwarzenbergská jízdárna, Hluboká nad Vltavou

1988

Theodor Pištěk, Ústřední kulturní dům železničářů, Praha

1984

Theodor Pištěk, Galerie umění Karlovy Vary, Karlovy Vary

1982

Obrazy, kresby, film, Galerie Václava Špály, Praha

1978

Theodor Pištěk, Galerie Nová síň, Praha

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2010

Realita je víc než fikce: Asambláž jako tvůrčí princip v českém umění 60. a 70. let, Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Brno

2007

Skupina Máj 57, Pražský hrad, Císařská konírna, Praha

České umění XX. století: 1970-2007, Alšova jihočeská galerie v Hluboké nad Vltavou

2006

Šedesátá / The sixties ze sbírky Galerie Zlatá husa v Praze, Galerie umění Karlovy Vary,

Bedřich Dlouhý, Jan Koblasa, Jan Kotík, Theodor Pištěk: Emigrace out/in 2, Saarländische Galerie – Europäisches Kunstforum e.V., Berlín

2005

Pocta Františku Kupkovi, Galerie 10, Praha

2004

Šedesátá / The sixties ze sbírky Galerie Zlatá husa v Praze, Dům umění města Brna, Brno

2003

Hyperrealismus, Západočeská galerie v Plzni, Plzeň

2000

Umění zrychleného času. Česká výtvarná scéna 1958 - 1968, Státní galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu, Cheb

Současná minulost. Česká postmoderní moderna 1960-2000, Alšova jihočeská galerie v Hluboké nad Vltavou, Hluboká nad Vltavou

Dva konce století 1900 2000, Dům U Černé Matky Boží, Praha

1999

Umění zrychleného času. Česká výtvarná scéna 1958 - 1968, Praha, Praha

1997

Umění zastaveného času / Art when time stood still, Česká výtvarná scéna 1969-1985, Brno

Umění zastaveného času / Art when time stood still, Česká výtvarná scéna 1969-1985, Státní galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu, Cheb

1996

Fineart ´96, Valdštejnská jízdárna, Praha

I. nový zlínský salon, Zlín

Umění zastaveného času / Art when time stood still, Česká výtvarná scéna 1969-1985, Praha

1993

Skutečnost a iluze, Zámek Hluboká nad Vltavou, Hluboká nad Vltavou

Záznam nejrozmanitějších faktorů… České malířství 2. poloviny 20. století ze sbírek státních galerií, Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha

1991

Šedá cihla 78/1991, Dům umění města Opavy, Opava

Šedá cihla 78/1991, Galerie U Bílého jednorožce, Klatovy

1990

Dialog ´90, Mánes, Praha

Pocta umělců Jindřichovi Chalupeckému, Městská knihovna, Praha

1988

České zátiší 20. století, Alšova jihočeská galerie v Hluboké nad Vltavou

Forum 1988, Holešovická tržnice, Praha

1986

České umění 20. století, Alšova jihočeská galerie v Hluboké nad Vltavou, Hluboká nad Vltavou

1984

Česká kresba 20. století ze sbírek Alšovy jihočeské galerie, Alšova jihočeská galerie v Hluboké nad Vltavou, Hluboká nad Vltavou

1981

České malířství a sochařství 1900 - 1980, Alšova jihočeská galerie v Hluboké nad Vltavou

Netvořice ´81, Dům Bedřicha Dlouhého, Netvořice (Benešov)

1968

Klub konkrétistů a hosté, Oblastní galerie Vysočiny v Jihlavě, Jihlava

Klub konkrétistů a hosté, Dům kultury pracujících, Ústí nad Labem

300 malířů, sochařů, grafiků 5 generací k 50 létům republiky, Praha

1967

Výstava mladých ´67, Výstavní síň Ústředí lidové a umělecké výroby, Praha

1966

Jarní výstava 1966, Mánes, Praha

Výstava mladých, Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Brno

1964

Tvůrčí skupina Máj, Galerie Nová síň, Praha

- Collections

-

Alšova jihočeská galerie v Hluboké nad Vltavou, Hluboká nad Vltavou

Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny

Galerie hlavního města Prahy

Galerie umění Karlovy Vary, Karlovy Vary

Národní galerie v Praze, Praha

Oblastní galerie v Liberci, Liberec

Oblastní galerie výtvarného uměni, Jihlava

Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích, Litoměřice

Státní židovské muzeum, Praha

Monography

- Monography

Musilová Helena , Martin Dostál, Theodor Pištěk - ecce homo, Národní galerie v Praze, Praha 2012