- First Name

- Tono

- Surname

- Stano

- Born

- 1960

- Birth place

- Zlaté Moravce, Slovakia

- Place of work

- Prague

- Keywords

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

In the Czechoslovak environment of the 1980s the works of Tono Stano looked like apparitions. After he graduated from the Secondary School of Applied Arts in Bratislava where due to limited capacity he was accepted into the Studio of Photography headed by Milota Havránková instead of the Studio of Graphics, he worked as a film photographer for one year. Later during 1980–1986 he and his classmates at FAMU – Miro Švolík, Vasil Stanko, Rudo Prekop, Kamil Varga and Peter Župník (photographers referred to as the Slovak New Wave) broke all the existing assumptions about what is photography.

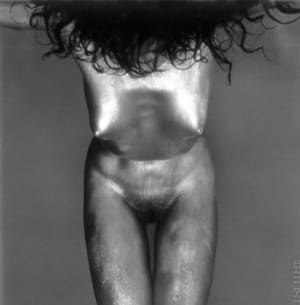

It is precisely the creative student years and Stano’s work until the first half of the 1990s that, in retrospect, appear to be the most interesting also for the reason that he was one of those who helped to open up until then inaccessible topics for photography. Whether it is the new erotic wave that was strongly tabooed during the Communist regime, staged photographs elevated to the level of free art, or the irony and exaggeration, which until then primarily documentary photography was avoiding.

However, the work of Tono Stano cannot be perceived individually and separated from the stream of the above-mentioned names, because it is without any doubt that the individual artists strongly influenced one another. An example of a collective engagement is the exhibition Hra na čtvrtého (Playing the Forth), which took place in Fotochema in Prague in 1986 with Rudo Prekop and Michal Pacina. Every one of them photographed a series of one part of the human body, and the photographs were exhibited above each other and in lines. In her introductory speech, Anna Fárová said the following about this project: “The principle of this exhibition is completely new for photography. The forth is the viewer. He is supposed to complete what the artists offered to him. (…) In today’s time of postmodernism, which eclectically borrows from all styles, includes metaphor and is entertained by a gag, which philosophically revels in historical memory and additive principles, this game of three artists on the forth has perfect timing.”

A similar overlap to “postmodernism” is visible also from the parallel with the photographic group Brotherhood. At the end of the 1980s it introduced in its collective exhibitions photographs drawing formally from older artistic streams and at the same time it borrowed figures ideologically emphasized by the former regime and visually conforming for socialistic realism. Tono Stano opened this visual game in his work Calendars 1985–1986, when he used and partially ironized allegories of industry or agriculture. Typical characteristic for his nude photographs and portraits not only from the 1990s is their dynamics. Despite the fact that Stano’s old-master approach resembles photographers such as Ivan Pinkava, the model on his technically perfect photographs creates the impression that it will jump out of its pose any moment. Many of his pictures are directly staged snapshots of a body frozen in motion.

Although, Tono Stano is one of the most respected photographers, his later works have shifted towards glamour and fashion photography, which distanced him from contemporary conceptually perceived art work, treating photography in a different way. In a similar way Stano fell silent in exhibiting. A new comeback was his exhibition in the Leica Gallery where he introduced his coloured photographs out of which several originated together with his continuous – often almost graphical – work, but most of them are from the 2010s.

- Author of the annotation

- Tereza Hrušková

- Published

- 2016

CV

1980-1986

School of Film, Photography and Television (FAMU) in Prague

1975-1979

Secondary school of applied arts in Bratislava

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

(selected)

2004

Institut Fran¢ais, Budapest

Galerie Baudelaire, Antwerp

2002

Fascination, Galerie G4, Cheb

Galerie Waldburger & Slovak Institute & Czech Centre, Berlin

Fascination, Dům umění, Brno

Czech Centre Bratislava

Fascination, Galerie Fiducia, Ostrava

2001

Fascination, Prazsky Dum Fotografie, Prague

Photo l.a., booth of Galerie Waldburger/photofront, Los Angeles

2000

Schoren, St. Gallen, Switzerland

1996

Galerie Marzee, Nijmegen

Dom kultury, Bratislava

1995

National Technical Museum, Prague

1993

Ambrosiana, Brno

1992

Galerie U Řečických, Prague

1990

Le pont neuf Gallery, Paris

Centre Culturel des Prémontrés, Pont-à-Mouson

Galerie G4, Cheb

Mala gallery, Warsaw

Fondation Nationale de la Photographie, Lyon

1989

Musée Lapidaire, Lectoure

Galerie G4, Cheb

1988

Galerija Ars, Ljubljana

1987

Galerie Fabrik, Hamburg

1986

Fotochema, Prague

1985

Walbrzyska Galeria Fotografií, Walbrzych

1984

FAMU, Lázaňský palác, Prague

Galeria fotografií Okno, Legnica

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2005

The Nude in Czech Photography, Kostis Palamas Hall, Athens

2004

Umělecká beseda Slovenská, Bratislava

2002

Dom umenia, Bratislava

Fotobiennale, Moscow

Czech Centre, Paris

2000

The Nude in Czech Photography, Císařská konírna Pražskékeho hradu, Prague

1999

Czech photography in the 1990s’, Chicago Cultural Centre, Chicago

Vartu, Vilnius

Mücsarnok, Budapest

Czech and Slovak Staged Photography, Czech Centre, New York

Contemporary Czech & Slovak Photography, David Scott Gallery, Toronto

1998

Czech Photography in the 20th Century, The Eli Lemberger Museum of Photography, Tel-Hai, Israel

1997

The Body in Contemporary Czech Photography, Macintosh Gallery, Glasgow

Salmovsky palace, Prague

10 ans de photographie , Reims

1996

Národní Galerie, Prague

1995

Galerie G4, Cheb

1994

After the velvet revolution: Contemporary Czech and Slovak Photography, The Photography Gallery of Western Australia, Perth

Prague House of Photography, Prague

1993

In & Out of Czechoslovakia, The Zelda Cheatle Gallery, London

Preview, Galerie Marzee, Nijimegen

A la recherché du père, Nouveau Forum des Halles, Paris

Czech & Slovak Photography, Spencer Museum of Art, Kansas

Between Image & Vision, Ironworks Gallery, Coatbridge

What’s new: Prague, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

1991

Slovak Staged Photography, Museum of Dance, Stockholm

Zeitgenössische Tschechoslowakische Fotografie, Kunsthaus, Hamburg

Photographie Tchécoslovaque 1940-1990, Centre Culturel, André Malraux, Vandeouvre-lès-Nancy

Photographie Tchécoslovaque 1940-1990, L’Aubette, Strasbourg

Die neue Kontinuität 1970-1990, Progressive Fotografie in der Tschechoslowakei, Städtisches Museum, Mühlheim

Contemporary Czechoslovak Photography, Exposition Park, Tokyo

1990

La Tchécoslovaquie à Arles, Palais de l’Archevêché, Arles

Photographie progressive en Tchécoslovaquie 1920-1990, Galerie Robert Doisneau, Nancy

Slovak Photography of the 1980s’, Warsaw and Moscow

Positivität, Fotogalerie, Vienna

Vision d’Homme, Chatêau d’Eau, Toulouse

Czech Symbolism, Výstavní síň Uluv, Prague

1989

Prix Air France, Ville de Paris, Paris

French Institute, Prague

Prager Trio, Czechoslovak Centre, Berlin

Junge Photographen aus der CSSR, Galerie Treptow, Berlin

Four Photographers from Prague, Aix-en-Provence

1988

Preis für junge europäische Photographen, Galerie Faber, Vienna

De Prague et de Bohême, Espace Jules Verne, Brétigny sur Orge

Questioning Europe, Photography Biennale, Rotterdam

Fotochema, Prague

1987

Preis für junge europäische Photographen, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt

Galerie G4, Cheb

1986

La jeune photographie Tchécoslovaque, Arena, Arles

Mánes, Prague

UPM, Prague

1985

27 Contemporary Czechoslovak Photographers, The Photographer’s Gallery, London and Bristol

Ursprung und Gegenwart tschechoslowakischer Photographie ,Fotografie Forum, Frankfurt

Il nudo nella fotografia dell’Est Europa, Torina Fotografia ’85, Torino

1984

FOMA, Prague

- Collections

-

(selection)

Art Institute, Chicago

Bibiliothèque Naionale, Paris

Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris

Moravská galerie, Brno

Museum Ludwig, Köln

National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, Bradford

Slovenská Narodná galleria, Bratislava

Uměleckoprumyslové museum, Prague