- First Name

- Vladimír

- Surname

- Janoušek

- Born

- 1922

- Birth place

- Přední Ždírnice u Nové Paky

- Place of work

- Prague

- Died

- 1986

- Lived and worked in

- Prague

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

Vladimír Janoušek came from eastern Bohemia towards which he maintained a personal tie throughout his whole life. Following the separation of Sudetenland, his family moved to Upice where Janoušek graduated from secondary school. He originally wanted to study architecture but he eventually started attending the Brno school of arts and crafts which shifted his interest towards fine arts. He did not complete his studies, however, because in 1941 he was forced to join the forced labour in the Third Reich. It was not until after the war that he continued to study at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, from where he graduated in 1950.

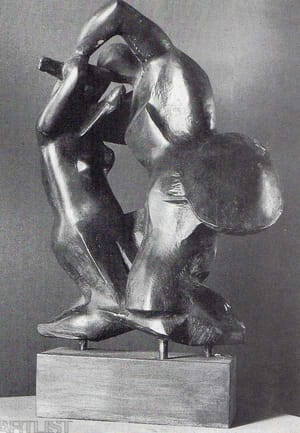

The beginnings of Janoušek’s work were influenced by his study in the studio of Josef Wagner and his friendships with his classmates including Věra Havlova (his future wife, sculptress Věra Janoušková), Zdeněk Palcr, Miloslav Chlupáč, Olbram Zoubek or Eva Kmentová. Their generational effort was to find an expression that would oppose the ideologically formed schematism of the Socialistic Realism. Back then the artists were finding support mainly in the interwar avant-garde, especially in France (moderate figural modernism, e.g. Henri Luarens, Ossip Zadkin, Jacques Lipschitz, Constant Permeke, and from the younger ones the Englishman Henry Moore). From the Czech tradition Janoušek related to Czech Cubism (Army, 1958, Head, 1961).

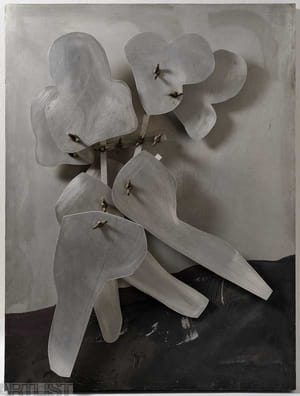

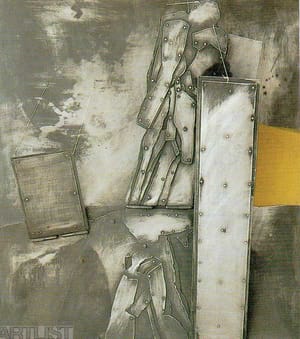

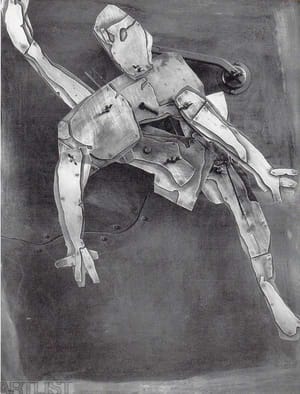

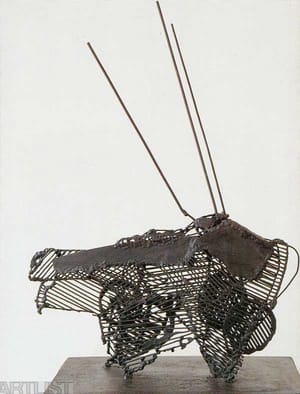

Janoušek finds his own expression around the mid 1960s. He learned to weld metal at the beginning of the 1960s and that was the determining factor for his future work. His statues started to lose traditional volume. Number of shapes is outlined by wire constructions. The overall impression is expressive and disturbing. “... they were figures surrounded by wire constructions, which marked their closest living space. It was too tight, however, to be able to say that it was a guarantee of peace and happiness. It looked more like a cage instigating its captives to escape, which increased the tension”, Jaromír Zemina states in his text. Janoušek’s main subject is the figure, which is strongly stylized into a prolonged image (Figure with the Motif of Time, 1966, Eternal Walker, 1966). During the second half of the 1960s Janoušek’s statues start to show an increasingly intense high-tech character – the statues look like some sort of machine mechanisms. This is completed by the element of a pendulum, which the sculptor took a fancy to and which became typical for his work. Towards the close of the decade Janoušek made a monumental composition out of cut out and welded sheet metal called

Hrozba války (Threat of War) (1968-69). The statue was intended for the Czechoslovak pavilion at the world exhibition in Osaka (1970). Janoušek conceived this piece in a political way: a line of apocalyptic militant figures marching from the Soviet pavilion with their guns poised at the neighbouring Czechoslovak pavilion. Following this event Janoušek became undesirable during the Normalization period for his uncompromising attitude. His proposals were excluded from public tenders and he was not allowed to exhibit.

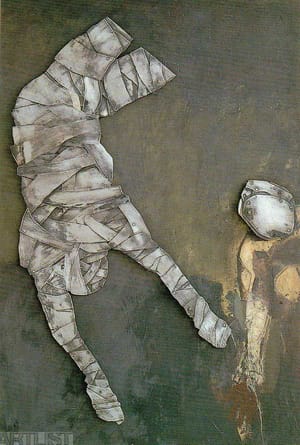

The element of motion captivated Janoušek so much that it became dominant for his entire future work. During the 1970s he started to create statues-reliefs, parts of which can be adjusted in various positions (Krajina [Landscape], 1979). These variations lost Janoušek’s previous jagged expressivity and they developed a constructive character. Gradually the flatness of his relief forms changed to free sculpture, in which Janoušek continued to work with flat metal sheets. His work contained the author’s bitter confession reacting to his fate of being forced to live in seclusion. His statues became a symbolical expression of an individual’s battle or fall caused by exterior circumstances, which is confirmed by some of his titles such as Násilí (Violence) (1984), Terč (Target) (1984-85) or several of his statues entitled Pád (Fall).

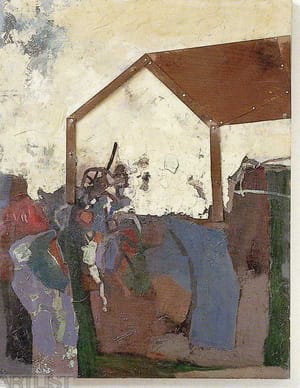

Janoušek was primarily a sculptor, but he was also engaged in painting and drawing. However, he used to add three-dimensional elements to his paintings; therefore, we can refer to them rather as reliefs. His paintings were often of landscapes, primarily those that he was near to: below the Krkonoše Mountains region. Together with his wife, Věra Janoušková, since 1975 they often used to work at their country home in Vidonice near Pecka (below the Krkonoše Mountains). In his drawings, Janoušek used to use pen and ink, and the drawings related to his sculptures with respect to their subject.

Vladimír Janoušek entered Czech history as a sculptor using new sculpting techniques. First it was welding and then mounted statues – sheet metal, screws, nuts, strings and draw bars are an inseparable part of his work. His new technique of making a statue was also steered by the internationally spread direction – Kinetic art. Movement in Janoušek’s work is not active, but it is only suspected or possible by shifting, opening or turning individual elements. With his innovative processing of the figure he can also be considered as a representative of new figuration, which was one of the important tendencies of Czech art during the 1960s and 1970s.

- Author of the annotation

- Ivona Raimanová

CV

Studies:

1945-1950 Academy of applied arts, architecture and design, Prague, J. Wagner

1941-1942 School of Applied Arts Brno

before 1940 High School in Trutnov, Bedřich Mudroch

- Member of art groups included in ARTLIST.

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2002

Věra Janoušková, V. J. Galerie Ars, Brno. Galerie Vysoké školy uměleckoprůmyslové, Praha (Prague)

V. J. Kresby a obrysové sochy. Galerie Jiřího Jílka, Šumperk

V. J. Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny.

1999

V. J. Pohyb a změna v plastice. Galerie Millennium, Praha (Prague)

1998

V. J. neznámý. Městské muzeum Hořice. Oblastní galerie Vysočiny v Jihlavě. Galerie U Bílého jednorožce v Klatovech, Galerie Klatovy / Klenová.

1997

V. J. Výstavní síň Synagoga, Hranice.

1993

V. J. Městské muzeum Nová Paka.

V. J. Galerie plastik Hořice.

1991

Věra Janoušková. Koláže. V.J. Kresby. Sovinec.

1990

V. J. Dům U Kamenného zvonu, Galerie hlavního města Prahy.

V. J. Kresby. Galerie d, Praha (Prague)

1989

V. J. 1922 - 1986. Malá galerie sbírky moderního sochařství na Zbraslavi, Národní galerie v Praze.

1987

V. J. Galerie Opatov, Praha (Prague)

V. J. Sochy. Ústřední kulturní dům železničářů, Praha (Prague)

1982

V. J. Obrazy a kresby. V. s. Domu kultury, Orlová.

V. J. Plastiky. Ústav makromolekulární chemie, Praha (Prague)

1967

Kyvadla a jiné sochy Vladimíra Janouška. Galerie Nová síň, Praha (Prague)

Věra Janoušková, V. J. Sochy. Oblastní galerie v Liberci

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2010

Roky ve dnech. České umění 1945-1957. Městská knihovna, Galerie hlavního města Prahy.

2009

Socha a město Liberec 1969. Výstava o výstavě. Oblastní galerie v Liberci.

2008

Nechci v kleci! Muzeum umění Olomouc.

2006

Šedesátá. Ze sbírky Galerie Zlatá husa v Praze. Galerie umění Karlovy Vary.

2005

Privátní pohled. Sbírka Josefa Chloupka. Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Dům umění města Brna.

2004

Za sklem. Ze sbírky Jaroslava Krbůška. Galerie Jiřího Jílka, Šumperk.

Šedesátá. Ze sbírky Galerie Zlatá husa v Praze. Dům umění města Brna.

2002

Anima & Animus. Manželské páry v generaci 60. let. Galerie Zlatá husa, Praha.

2001

Barevná socha. Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích.

2000

Umění zrychleného času. Česká výtvarná scéna 1958 - 1968. Státní galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu.

Dva konce století 1900 2000. Dům U Černé Matky Boží, ČMVU Praha.

1999

Přírůstky sbírek státních galerií z let 1990 - 1997. Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha.

Umění zrychleného času. Česká výtvarná scéna 1958 - 1968. ČMVU Praha.

1998

Oznámení o Ikarově letu. Olomoucká šedesátá léta. Muzeum umění Olomouc.

1997

Umění zastaveného času. Česká výtvarná scéna 1969-1985. Moravská galerie v Brně. Státní galerie výtvarného umění v Chebu.

Mezi tradicí a experimentem. Práce na papíře a s papírem v českém výtvarném umění 1939-1989. Muzeum umění Olomouc.

Česká koláž. Palác Kinských, NG v Praze.

1996

V prostoru 20. století. České umění ze sbírky Galerie hlavního města Prahy. Městská knihovna, GHMP.

Umění zastaveného času. Česká výtvarná scéna 1969-1985. ČMVU Praha.

1994

Nová figurace, Moravská galerie v Brně. Dům umění v Opavě. Oblastní galerie Vysočiny v Jihlavě.

UB 12. Galerie moderního umění v Roudnici nad Labem. Oblastní galerie Vysočiny v Jihlavě. Galerie umění Karlovy Vary.

Ohniska znovuzrození. Městská knihovna, GHMP.

1993

Nová figurace. Galerie výtvarného umění Litoměřice. Východočeská galerie v Pardubicích.

1992

Světlo v tmách. Považská galéria umenia, Žilina.

Minisalon. Galerie Nová síň, Praha.

20 let výtvarných výstav v Makru (1972 - 1992). Ústav makromolekulární chemie (ÚMCH), Praha.

1991

Hýbače, Východoslovenská galéria, Košice. Národní technické muzeum, Praha

Šedá cihla 78/1991. Galerie Klatovy / Klenová. Dům umění v Opavě.

In memoriam. Mánes, Praha.

Tradition und Avantgarde in Prag. Kunsthalle Dominikanerkirche, Osnabrück. Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn

1990

Pocta umělců Jindřichovi Chalupeckému. Městská knihovna, GHMP.

1989

České sochařství 1948 - 1988. Krajské vlastivědné muzeum Olomouc.

1988

Pohyb. Galerie H , Kostelec nad Černými lesy.

Forum 1988. Holešovická tržnice, Praha.

Contemporary Art in Czechoslovakia: Selections from the Jan and Meda Mladek Collection. Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, New York.

1986

A4, Galerie H , Kostelec nad Černými lesy (Praha-východ)

1985

Barevná socha. Galerie H, Kostelec nad Černými lesy.

1984

Velká kresba. Galerie H , Kostelec nad Černými lesy.

Čtyřverší. Galerie H, Kostelec nad Černými lesy.

1983

Prostor, architektura, výtvarné umění. Výstaviště Černá Louka, Ostrava.

Krabičky. Galerie H, Kostelec nad Černými lesy.

1981

Boje a zápasy českého moderního umění. Výstava na počest 60.výročí založení KSČ. Oblastní galerie v Liberci.

Netvořice ´81. Dům Bedřicha Dlouhého, Netvořice.

1980-1981

Eleven contemporary Artists from Prague, New York University, New York. Rackham Galleries, Ann Arbor.

1980

Kresby českých sochařů. Divadlo hudby OKS, Olomouc.

1971

Češka skulptura XX vijeka. Umjetnicka galerija BiH. Sarajevo.

1970

Nová figurace. Dům umění města Brna.

Tschechische Skulptur des 20. Jahrhunderts. Von Myslbek bis zur Gegenwart. Schloß Charlottenburg - Orangerie, Berlín.

1969

L´art tcheque actuel. Renault Champs - Élysées, Paříž.

Arte contemporanea in Cecoslovacchia. Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea (GNAM), Řím.

Nová figurace. Mánes, Praha.

Socha a město. Liberec.

1968

Deset sochařských vyznání. Galerie Fronta, Praha.

Nové věci. Galerie Václava Špály, Praha.

Socha piešťanských parkov '68. Kúpelový ostrov, Piešťany.

300 malířů, sochařů, grafiků 5 generací k 50 létům republiky. Jízdárna Pražýského hradu, Praha.

1967

Umělci k výročí Října. Bruselský pavilon, Praha.

Mostra d´arte contemporanea cecoslovacca. Castello del Valentino, Turín.

1966

Jarní výstava 1966. Mánes, Praha.

Aktuální tendence českého umění. Obrazy, sochy, grafika. Praha.

Tschechoslowakische Plastik von 1900 bis zur Gegenwart. Museum Folkwang, Essen.

1965

Tschechoslowakische Kunst heute. Profile V. Städtische Kunstgalerie, Bochum.

Sochařská bilance 1955-1965. Olomouc.

La transfiguration de l´art tchéque. Peinture - sculpture - verre - collages. Palais de Congres, Liege.

1964

Tvůrčí skupina UB 12. Galerie Nová síň, Praha.

Socha 1964. Liberec.

1963

Rychnov 1963, Zámek Rychnov nad Kněžnou.

1962

Tvůrčí skupina UB 12. Galerie Československý spisovatel, Praha.

1961

Realizace. Galerie Václava Špály, Praha.

1960

Tvůrčí skupina v Umělecké besedě. Obecní dům, Praha.

Soudobé české malířství 1945 - 1960. Dům umění, Olomouc.

1959-1960

4. přehlídka československého výtvarného umění. Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha.

1958-1959

Umění mladých výtvarníků Československa 1958. Obrazy a plastiky. Jízdárna Pražského hradu, Praha.

1958

Umění mladých výtvarníků Československa 1958. Obrazy a plastiky. Dům umění města Brna.

1953-1954

Členská výstava Umělecké besedy. Valdštejnský palác, Praha.

1953

Členská výstava Umělecké besedy. Slovanský ostrov, Praha.

- Collections

-

České muzeum výtvarných umění, Praha

Galerie hlavního města Prahy, Praha

Museum Kampa - Nadace Jana a Medy Mládkových, Praha

Národní galerie v Praze, Praha

Oblastní galerie v Liberci, Liberec

- Other realisations

1981

Křídla, mobilní plastika, Třebíč

1971

Krystal vzduchu, nádvoří školy, Kladno-Kročehlavy

1970

Hrozba války, Expo v Ósace, symbolický protest proti okupaci Československa

1967

Expo Montreal

1966

Česká krajina, kašna, Jiřský klášter v Praze

1964

Slunce, plavecký stadion Podolí, Praha

1958

Hudba, Čs. pavilon Expo 58 Brusel

1955

reliéf, Dům módy v Praze

Monography

- Monography

1995 Jaromír Zemina, Vladimír Janoušek: Proč to dělám právě tak, Knihkupectví Portal, Uherské Hradiště

1990 Josef Hlaváček, Karel Srp, Jiří Šetlík, Vladimír Preclík, Galerie hl.m. Prahy

1967 Ludmila Vachtová, Vladimír Janoušek, Sochy. Oblastní galerie v Liberci

1962 Jiří Šetlík, Vladimír Janoušek, Nakladatelství československých výtvarných umělců, Praha