- First Name

- Vojtěch

- Surname

- Fröhlich

- Born

- 1985

- Birth place

- Prague

- Place of work

- Prague

- Keywords

- CSU Library

- ↳ Find in the catalogue

About artist

Over recent years the work of Vojtěch Fröhlich has deployed a relatively wide range of media and themes. It might appear as though his performances, installations, public interventions, film and photography was dissolving into a kind of arcane post-conceptual sphere, and some of his flippant ideas on the boundary of mundane everyday activities make the viewer question whether this is still art. This might involve his workshop on covering tourist bicycles with reflective foil (Prototype, 2011), cleaning out an inhabitable car during the private view (Úklid / Cleaning, 2012), or putting into operation the AVU Club with its own vegetable garden offering good quality refreshments to students and lecturers of the Academy of Fine Arts (2012 – ongoing). It is as though Fröhlich wants to investigate, experience and sample anything that pops up in his head and uses the world of art simply in order to do so. In addition, his themes and creative methods are often based on interests and skills outside the world of art, especially sport, which become the unexpected source of sensual experience, significance and emotion. A conceptual approach plays an important role in Fröhlich’s projects along with playfulness, an existentialism linked with the repeated motif of meditation, loneliness and the testing of one’s own physical possibilities, temporality and procedure. Filip Jakš mentions procedure in his review of an exhibition of works by Fröhlich and Sebastian Stumpf in the Drdova Gallery. Filip Jakš (rec.), Myšlení skulinkami. artalk.cz, 21.11.2014, http://www.artalk.cz/2014/11/21/mysleni-skulinkami/, referenced 9 June 2015. Fröhlich’s works and events are always site specific and the level of his investigation of the external and internal space plays an important role in his creative practice.

Fröhlich is keen on sports and often draws on physical activities, especially climbing or running, in his performances. It would be difficult to find another Czech artist working right now who would climb the walls of art schools and galleries. Though climbing is a theme explored by the Slovak artist Štefan Papčo, this artist prefers to bring his experiences into the static medium of sculpture. On the other hand Fröhlich, when he climbed from the entrance to the Academy of Fine Arts to the studios without touching the ground using duplicates of the interior decor (Cca..., 2011) or when he gave lessons in tightrope walking in the graduate show above the courtyard of the Trade Palace before and after opening hours (Flow 52/26, 2014), is above all interested in the physical act itself, the process of overcoming a certain impediment and the spiritual experience linked with this. He has put on several such performances (Plato (7-A0,RP 7+)16h. 23.9.2014, 2014; M4+, 2014 and Expedice r. 85, 2012), usually in the interiors and exteriors of galleries. He often mounts these acrobatic performances in real time, though in his recent exhibition at the Drdova Gallery he presented only a video documentary of his passage through the building in which the gallery is located. In his climbing performances Fröhlich uses all his motor and sensory possibilities to carry out a thorough examination of the environment that surrounds him and is not interested in its institutional character. Drawing on the differentiation of types of intelligence compiled by Howard Gardner one could say that Fröhlich combines a physical-kinetic intelligence that is underestimated in our logocentric civilisation and thus draws the viewer’s attention to alternative methods of understanding.

At first sight a parallel to Fröhlich¨s work would be that by the German duo of Matthias Wermke and Mischa Leinkauf, whose work consists of often demanding and (albeit only seemingly)´dangerous acts, for instance in climbing city constructions (Drifter, from 2012) or factory chimneys (Statt der 100 Türme, 2014). The Wermke-Leinkauf / Mischa Leinkauf duo certainly combines an unorthodox approach to mapping out space and architecture, though if we look more attentively we see that many aspects of their work are in antithesis to Fröhlich’s work and the artist himself does not see a direct ink. Their performances are usually preceded by a detailed historical and political analysis, have a somewhat larger scale (in terms of building size) and are usually presented in the form of videos or video installations. A significant aspect of their work is the fact that their projects are often illegal and thus an example of civil disobedience, which is not true of Fröhlich’s performances. However, his work too is about freedom and a kind of boyish pleasure in newly discovered lands.

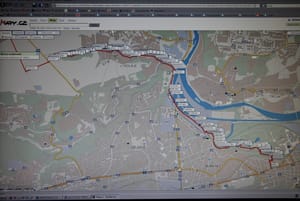

Another sport that Fröhlich has raised to an art form is running. In 2009 he was asked to organise an exhibition at the Benzínka “non-gallery”, which he discovered lies exactly 42.195 kilometres outside Prague, i.e. the same distance as a marathon. The run itself became a kind of private view rather than an exhibition, whose viewers were the handful of friends who visited Benzínka on that day and everyone who later heard about the event through word of mouth, articles and photographs. The project Srdíčko / Little Heart (2007) was based on a similar feat of endurance, in which Fröhlich resolved to travel in a route describing a heart drawn around the Czech Republic beginning and ending in Prague. Demanding events involving a marathon or triathlon also form the subject matter of the Dutch artist Guido van der Werve. His cross-country pilgrimages captured in his films are often accompanied by a strong narrative element and his own musical accompaniment. The resulting works are highly aestheticised in the style of Wermke-Leinkauf, which has led some critics to use the term “romantic conceptualism”, first used by the critic and curator Jörg Heiser when describing a trend in contemporary art based on the tradition of conceptual art but interrogating its original analytical and rational style with a large dose of subjectivity and intuition [e.g. Xander Karskens (rec.), Romantic Subversion: Acts of In-Between-ness, wermke-leinkauf.com, http://www.wermke-leinkauf.com/en/texts/karstens, referenced 9 June 2015.; Jennifer Higgie, Guido van der Werve, frieze, 2008, no. 114, duben, http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/guido_van_der_werve/, referenced 9 June 2015.; Jörg Heiser, Emotional Rescue, frieze, 2002, no. 71, 11.11., http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/emotional_rescue/, referenced 7 June 2015.]. To some extent the term can be used of Fröhlich. Like the other sports-artists intuition is important in his work as a trigger, alongside a conceptual approach supported by an awareness of artistic context. Fröhlich and van der Werve refer to physical activity as a manifestation of vitality and the running that features in their work has a similar existential dimension. However, the work of the Czech artist remains in a cruder form and the motif of solitariness and the expenditure of energy and self-overcoming impact upon us by means of directness and simplicity rather than the post-production beauty of a recording.

Fröhlich also tested his own physical and psychological limits in the double performance Křehké kino / Fragile Cinema (2012) at the Young Artists’ Gallery Brno and the Jelení Gallery Prague. While in Brno he spent 24 hours prior to the private view fiercely rotating the hands of a pocket watch to the beat of a second hand in order to suspend time for himself, in Prague he spent a week enclosed within pure darkness. Both performances took place with virtually no viewers. At the private view such viewers as there were were confronted with a video recording of the event and the venue of the day-long experiment as the artist abandoned it shortly after the exhibition opening, and in the second case they met a confused artist in a state comparable to being woken up after a week-long sleep. Both events are characterised by a seemingly senseless determination to persist and finish at any cost a pointless task the artist has set himself. The motif of loneliness is important and a concentration on one’s own being undisturbed by any surrounding influences and a certain type of rebirth that takes place after hours or days of suspended time. In this sense Fröhlich undoubtedly continues in the tradition of world performance (Chris Burden and Bruce Nauman) and specifically Czech performance (Petr Štembera, Jan Mlčoch and Karel Miler), that, though motivated by different political, social or purely aesthetic circumstances, nevertheless work from the start with the theme of the body, spirit, stamina and isolation.

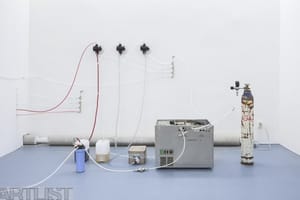

Fröhlich’s essays in photography and film are also based on monotonous, endless, even unfeasible work. The duet of works entitled oooOOO°°°...000 (2009) consisted of an attempt to punch holes in the centre of each frame of 16mm film and draw a regular circle on a piece of white paper. As we see in the animation linking up his drawings and in the group exhibition Křehké kino (2012), where he screened his perforated film, his desire to achieve perfection remains unfulfilled. These and other works have a distinctively meditative plane while also thematising the materialist and mechanical properties of these media. In the cycle of perforated photographs (..............................., 2008–2009) he focuses on pricking every bright spot in a black-and-white image. In the series Modřanská rokle / Modřany Gorge (2005) he rubbed pigments from plants located in the site of the scenery depicted into the photographs until they had absorbed the colour and aroma.

Fröhlich usually makes do with minimum of resources that as a consequence have a strong effect. The principle of the minor intervention formed the basis of his intervention in public space entitled Kolotoč / Roundabout (2011, with Ondřej Mladý, Jan Šimánek and Vladimír Turner) and Osvícení/ Enlightenment (2012, the same team), in which in both cases the artists “abused” municipal facilities intended mainly for the presentation of advertising on Barrandov Bridge. The first time round he used a revolving billboard as his own entertainment, the second he turned a street lamp away from the billboard and onto the monument to Josef Klimeš. He managed to achieve what is clearly the objective of every public event, namely an awareness and critique of what we do not see and a poetic and humorous objectification of the commonplace. Although it took place in a gallery, the last intervention by Fröhlich at the Zlín Salon of the Young (Obraz IV / Image IV, 2015) is also a subtle re-diverting of the viewer’s attention to that which is usually concealed, in this case the gallery depository. The artist achieved this simply by demolishing the partition wall dividing gallery and depository.

- Author of the annotation

- Klára Stolková / Peloušková

- Published

- 2015

CV

2008–2014

Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, studio of Miloš Šejn, Zbigniew Liber and Tomáš Vaněk

2006–2009

FAMU

internships, creative residencies:2014

The Residence at Villa Arson, Nice, France

2013Finnish Academy of Fine Arts, scholarship Erasmus

2015 - finalist of Jindřich Chalupecký Award

Exhibitions

- Solo exhibitions

-

2014

Bez názvu, Drdova Gallery (se Sebastianem Stumpfem), Praha

-1, Villa Arson, Nice

2013

2500,-, Galerie Fenester, Praha

Minimalistická rozcvička, Galerie D9 (ve spolupráci s Lucií Mičíkovou), České Budějovice

Nenápadný rozdíl mezi životem a smrtí, Galerie 35M2, Praha

2012

Osvícení, Off-limits, Fotograf Festival, Školská 28, Praha

Křehké kino, Galerie Jelení, Praha

Křehké kino, Galerie mladých, Brno

2011

Prototyp, Galerie 207, VŠUP, Praha

Cca..., AVU, Praha

2009

42,195, výstavní prostor Benzinka, Slaný

Moment nejistoty, Galerie Gamu, Praha

/////////, (ve spolupráci s Janem Šimánkem ), Galerie AVU, Praha

2006

Sněženka, Schodiště v Lažanském paláci (FAMU), Praha

- Group exhibitions not included in ARTLIST.

-

2015

Zlínský salon mladých 2015, Krajská galerie výtvarného umění, Zlín

Telepatie nebo esperanto, FUTURA, Praha

Loading ercury with a pitchfork, Nice Gallery London, London

2014

PLATOvideo1, Trojhalí Karolína, Ostrava

Diplomanti AVU 2014, Národní galerie, Praha

Cesta, Meetfactory, Prague

Zdálo se ti o horách?, České centrum, Praha

Pracoviště, Galerie Gamu, Praha

2013

Carte Blanche, Kuvataideakatemia Gallery, Helsinki

Byt či Nebyt, GAVU, Prague

The Image Object, Kuvataideakatemia Gallery, Helsinki

Festival Fluidum #4 ENDAGME!. Gallery K4, Prague

School Notes, Galerie Emila Filly, Ústí nad Labem

Crosstalk, video art festival, Budapest

Petites Résistances, Weltkunstzimmer, Düsseldorf

Entry Code, GAVU, Praha

Hi5!, Dům umění města Brna, Brno

The 9th International Directors Lounge, Urban Research program, Berlin

2012

PAF, Jiné vize 2012, XI. Přehlídka animovaného filmu, Olomouc

La perte du désir de plaisir, PCF, Place Voltaire, Arles

Konec světa, Galerie G99, Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Brno

Pohyb na místě, výstavní prostor Kokpit, Praha

6. Zlínský salon mladých, Dům umění, Zlín

Naslepo, výstavní prostor Kalvárie, Ostré u Úštěka

Ostrovy odporu. Mezi první a druhou moderností 1985 —2012, Národní galerie, Praha

Křehké kino, Galerie mladých, Brno

Zootropio film festival, Portugal, Porto

2011

Exit Award 2011, Galerie Emila Filly, Ústí nad Labem

Pavěda, Galerie Národní technické knihovny, Praha

Konečně spolu, Galerie Emila Filly, Ústí nad Labem

Planoucí, krutý, krásný a bledě růžový, Velvyslanectví České republiky, Berlín

Condition Report - New Photographic Art from the Czech Republic, Hoopers Gallery, London

2010

Condition Report - New Photographic Art from the Czech Republic, Turner House Gallery, Cardiff

Concepto Grosso, gallery Barcsay-terem, Budapest

Art plenér 010, galerie Bernarda Bolzana, Těchobuz

Haťapaťa, galerie Dvanáctka, Zlín

2009

Stopy a záznamy, 8. ročník fotografického festivalu Funkeho Kolín, Školská 28, Praha

Cesta s BP, galerie GAMU, Praha

Grafika roku 2008, Clam-Gallasův palác, Praha

2008

Konzervy komunismu, galerie GAMU, Praha

Neregulováno. Prales ve fotografii, Moravská galerie, Brno

Výstava FAMU, Photokina, Köln

Mezinárodní trienále současného umění, Re-Reading the Future, Národní galerie, Praha

GAME, galerie GAMU, Praha

Fire-fliers, Školská 28, vernisáž: 49 % OUCH! 51 % YEAH, Praha

2007

Nová témata v obraze, výstavní prostor Jiřího Jeníčka, Beroun

„66“ - II., Galerie Velryba

Randomix - Culture Differently, Trafačka Aréna, Praha

šestka/six - šest českých škol fotografie - Katedra fotografie FAMU, Pražský dům fotografie, Praha

2006

„Famu Prag“ Kunstverein Weiden e.V.,

„66“ Studenti FAMU, Galerie Velryba, Praha